Archaeology as History in the North Cascades Mountains

by Robert R. Mierendorf

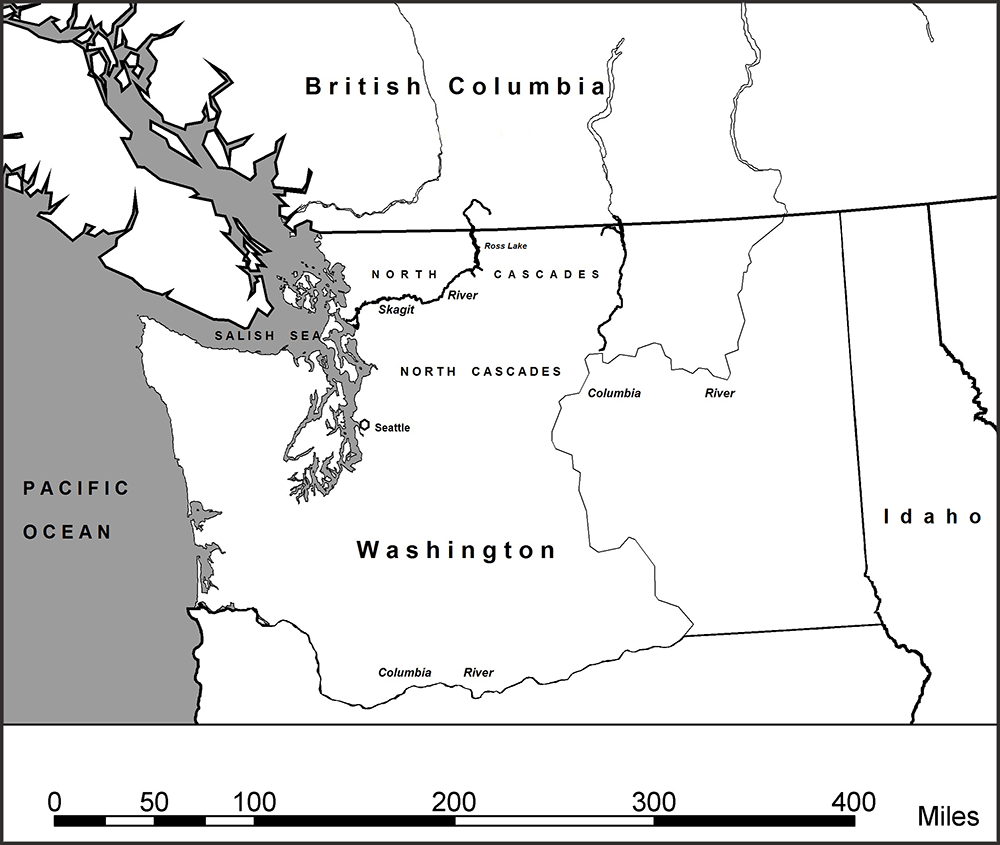

The North Cascades Mountains have a reputation as being steeper and more snow covered than most other mountains of the far western United States. Native people (also “American Indians” or “Native Americans”) thrived in these mountains for thousands of years and their languages, songs, and stories preserved essential details of their homeland, of environmental and social events, of their families’ histories, and of how specific places were created and named. Native villages, tribes, and nations of the North Cascades spoke, and still speak, several dialects of Salish (SAY-leesh), the general name for the native language of the Salish Sea (Puget Sound) and the surrounding mountains.

The North Cascades Mountains have a reputation as being steeper and more snow covered than most other mountains of the far western United States. Native people (also “American Indians” or “Native Americans”) thrived in these mountains for thousands of years and their languages, songs, and stories preserved essential details of their homeland, of environmental and social events, of their families’ histories, and of how specific places were created and named. Native villages, tribes, and nations of the North Cascades spoke, and still speak, several dialects of Salish (SAY-leesh), the general name for the native language of the Salish Sea (Puget Sound) and the surrounding mountains.

The North Cascades’ ruggedness resisted easy exploration and travel by European explorers in the 1800s. The later establishment of towns along the Salish Sea did not extend far into the North Cascades, particularly in the upper Skagit River valley. The Skagit is the largest river flowing out of the North Cascades and into the Salish Sea. It is the native homeland of Skagit peoples, who lived in long houses built of cedar wood. Their ancient villages once stretched along the banks of the Skagit River; their back yards ran up the valley walls to the mountaintops. They resisted government attempts in the late 1800s to remove them from their homeland. Today, the Upper Skagit Indian Tribe is one of several that thrive in their traditional North Cascades homeland.

Skagit Indian elders and anthropologists began to collaborate in the mid-1900s to preserve in writing and audio tapes all aspects of Skagit culture and history, a project that continues today. Archaeologists began studies in the Skagit valley around the same time.  Unlike other ways to know the past, archaeology is a way to learn history based on studying those things preserved in the environment from earlier societies and cultures. For example, in the remote wilds of North Cascades National Park, the past is preserved in many ways, including in the form of charred animal bones and plants in cooking areas, in storage pits dug into the ground, in art and picture-writing painted on cliff faces, in the earthen floors and other remnants of houses, and in work areas where objects, such as stone knives and points or stone axes to build a canoe, were made. Because these things are many centuries old, they are often found preserved under layers of soil, which helps to protect them.

Unlike other ways to know the past, archaeology is a way to learn history based on studying those things preserved in the environment from earlier societies and cultures. For example, in the remote wilds of North Cascades National Park, the past is preserved in many ways, including in the form of charred animal bones and plants in cooking areas, in storage pits dug into the ground, in art and picture-writing painted on cliff faces, in the earthen floors and other remnants of houses, and in work areas where objects, such as stone knives and points or stone axes to build a canoe, were made. Because these things are many centuries old, they are often found preserved under layers of soil, which helps to protect them.

Archaeologists first began to study the North Cascades around 1970, but not much was found and it was generally thought that native people spent little time in the mountains. After I became the archaeologist for North Cascades National Park, my team’s systematic archaeological excavations showed that nearly 10,000 years ago, the ancestors of today’s Skagit Indians were the first to explore, canoe, hike, camp, hunt, gather plants, prospect for minerals, and fish in the North Cascades.  Over that long history, they became experts about their environment. Their local knowledge base and skills provided them nature’s version of the hardware store, grocery, and pharmacy. Their now buried ancestral campsites are difficult to find, but they preserve the remains of ancient food cooking and heating pits. Some of the oldest of these were found at Cascade Pass, one of several traditional travel routes used to hike up and over the North Cascades. We also found similar ancient campsites down in the narrow forested valleys on both sides of Cascade Pass. The closest native village formerly sat at Marblemount, about twenty-five miles from the pass, where the Cascade and Skagit Rivers join.

Over that long history, they became experts about their environment. Their local knowledge base and skills provided them nature’s version of the hardware store, grocery, and pharmacy. Their now buried ancestral campsites are difficult to find, but they preserve the remains of ancient food cooking and heating pits. Some of the oldest of these were found at Cascade Pass, one of several traditional travel routes used to hike up and over the North Cascades. We also found similar ancient campsites down in the narrow forested valleys on both sides of Cascade Pass. The closest native village formerly sat at Marblemount, about twenty-five miles from the pass, where the Cascade and Skagit Rivers join.

The National Park Service conserves Cascade Pass and other park areas to keep them undisturbed and like they were in the pre-contact past (before European influences, about AD 1800). To learn about this earlier history of the pass, my archaeology crew carefully dug through thin layers of soil, through ash from the eruption of nearby volcanoes and through ancient campfire charcoal. The results showed that native people had been camping at Cascade Pass for at least 9,600 years. It was surprising to some, but not to others, that the site was this old.  Cascade Pass archaeology, at present, provides the earliest evidence of native peoples’ presence in the alpine (the highest and snowiest part of mountains where forests cannot grow) in the Cascade Mountains and other mountains of Washington State and southern British Columbia.

Cascade Pass archaeology, at present, provides the earliest evidence of native peoples’ presence in the alpine (the highest and snowiest part of mountains where forests cannot grow) in the Cascade Mountains and other mountains of Washington State and southern British Columbia.

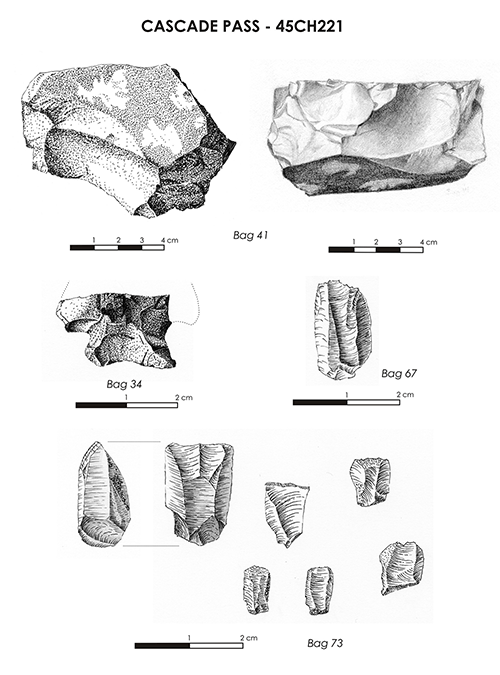

We found that many of the stone tools used at Cascade Pass were made from a unique blue-gray quartz rock. This sharp flint-like stone, called “Hozomeen chert,” comes from near the heart of the Upper Skagit Indian homeland, but far from Cascade Pass. Years earlier, our research discovered many ancient places in the Skagit valley where Indian ancestors gathered the chert. The largest of these stone quarries is at least 8,500 years old.  After we found tools made of Hozomeen chert at Cascade Pass, we concluded that Skagit Valley people carried the chert with them on their camping trips to the high mountains. After tracing on a map all places where these chert tools have been found, the resulting pattern of dots shows the routes used by Skagit people to cross over the North Cascades.

After we found tools made of Hozomeen chert at Cascade Pass, we concluded that Skagit Valley people carried the chert with them on their camping trips to the high mountains. After tracing on a map all places where these chert tools have been found, the resulting pattern of dots shows the routes used by Skagit people to cross over the North Cascades.

The different artifacts found in the soil layers at the pass, such as stone knives, spear and arrow tips, and charred plant parts, showed that people hunted animals and collected berries for food. They also burned mostly pine tree branches to heat the rocks in the cooking fires. Because pine trees and forests today grow far from Cascade Pass, finding pine charcoal in the old cooking pits could mean that the surrounding climate was different—pine trees like it cooler and drier than today’s climate at the pass. Only scattered fir and hemlock grow around the pass now, as these trees are best adapted to the winter snow pack, which becomes feet deep by the end of winter. The deep snow melts by mid-summer, the season when hikers and mountain goats come to enjoy the green alpine meadows.

The different artifacts found in the soil layers at the pass, such as stone knives, spear and arrow tips, and charred plant parts, showed that people hunted animals and collected berries for food. They also burned mostly pine tree branches to heat the rocks in the cooking fires. Because pine trees and forests today grow far from Cascade Pass, finding pine charcoal in the old cooking pits could mean that the surrounding climate was different—pine trees like it cooler and drier than today’s climate at the pass. Only scattered fir and hemlock grow around the pass now, as these trees are best adapted to the winter snow pack, which becomes feet deep by the end of winter. The deep snow melts by mid-summer, the season when hikers and mountain goats come to enjoy the green alpine meadows.

Archaeological evidence from Cascade Pass helps to reconstruct ancient hiking routes, campsite locations, and hunting and gathering areas. From it, we are able to piece together details of what people ate and the ways foods were cooked. However, it is important to remember that many Skagit Indian people today are not surprised to learn of these details. This is because Upper Skagit Indian elders remember that Cascade Pass and the North Cascades were important places in their homeland’s history. “Cascade Pass” in their language means “over the mountain.” According to the traditional teachings of Upper Skagit Indians, the first crossing of the North Cascades began in legend time, when their earliest ancestors traveled up the Skagit Valley along the river and crossed over to the other side of the North Cascades Mountains to the Columbia River.

Archaeological evidence from Cascade Pass helps to reconstruct ancient hiking routes, campsite locations, and hunting and gathering areas. From it, we are able to piece together details of what people ate and the ways foods were cooked. However, it is important to remember that many Skagit Indian people today are not surprised to learn of these details. This is because Upper Skagit Indian elders remember that Cascade Pass and the North Cascades were important places in their homeland’s history. “Cascade Pass” in their language means “over the mountain.” According to the traditional teachings of Upper Skagit Indians, the first crossing of the North Cascades began in legend time, when their earliest ancestors traveled up the Skagit Valley along the river and crossed over to the other side of the North Cascades Mountains to the Columbia River.

Archaeology can bring to light details, events, and histories of past societies that have been lost or long forgotten. In the North Cascades, archaeology tells us that Salish people and their ancestors were closer to, and more familiar with, the North Cascades alpine than any historic documents and records had indicated. In addition, archaeology uncovers environmental evidence of the past, such as changes in vegetation and climate or volcanic eruptions. For today’s Skagit Indian tribes and their governments, such evidence agrees well with ancestral beliefs and stories. As a result, archaeological data about the distant past offers a tangible connection linking today’s native peoples (tribes and first nations) with their ancestors: the first inhabitants, societies, and nations of the North Cascades Mountains. Finally, archaeology reminds all of us that the past is so much more than just a fading echo off the valley walls; rather, it creates the stream of history in which we all swim.

Archaeology can bring to light details, events, and histories of past societies that have been lost or long forgotten. In the North Cascades, archaeology tells us that Salish people and their ancestors were closer to, and more familiar with, the North Cascades alpine than any historic documents and records had indicated. In addition, archaeology uncovers environmental evidence of the past, such as changes in vegetation and climate or volcanic eruptions. For today’s Skagit Indian tribes and their governments, such evidence agrees well with ancestral beliefs and stories. As a result, archaeological data about the distant past offers a tangible connection linking today’s native peoples (tribes and first nations) with their ancestors: the first inhabitants, societies, and nations of the North Cascades Mountains. Finally, archaeology reminds all of us that the past is so much more than just a fading echo off the valley walls; rather, it creates the stream of history in which we all swim.

Robert R. Mierendorf has resided in the Pacific Northwest since 1970. He has degrees in anthropology from Iowa State and Washington State Universities and has participated in archaeological field projects in the Pacific Northwest, Midwest, and Southwestern regions. From 1986 to 2013 he served as park archaeologist at North Cascades National Park. His research interests include the pre-contact history of indigenous Northwest mountain peoples, Pleistocene and Holocene archaeology, paleoecology, and the natural history of the North Cascades. Currently working as a consultant in Duvall, Washington, he is the author of professional journal articles, technical reports, and educational publications relating to the North Cascades and Northwest Native Americans.