American Sabor: A Guided Playlist of Latino Music

by Marisol Berríos-Miranda and Shannon Dudley

The word sabor in Spanish evokes the delights of music, as well as food. It signifies a rich essence that makes our mouths water, or makes our bodies want to move. In this article we highlight a few songs by Latinos and Latinas that have contributed to the sabor of American music. Recorded between 1958 and the present, these songs have been heard all across the United States through radio, records, and other media. They represent “American” music in the sense that they originate in the US, but they also make musical connections to a broader America that includes the Caribbean, Central America, and South America. Not only are they windows onto Latino histories, they also represent a musical legacy that enriches us all.

(The songs discussed here, except for “La Murga,” “Despacito,” and “Conga,” can be heard on the Spotify playlist titled “American Sabor.” Further listening resources are available on the companion website to our bilingual book: americansabor.music.washington.edu)

*****

“Oye Como Va,” Santana (1970)

With its opening exclamation of “Sabor!” this recording affirmed the arrival of Latin music in the mainstream of American popular music, where timbales, congas, cowbell, and güiro could share the stage with Carlos Santana’s wailing electric guitar.

The original version of “Oye Como Va” was a cha cha chá recorded in 1962 by Nuyorican (New York-born Puerto Rican) bandleader Tito Puente. In the decades following World War II the bands of Tito Puente, Machito, and Tito Rodriguez played in New York City ballrooms like the Palladium on 53rd Street and Broadway where Latinos, Jewish Americans, Italian Americans, African Americans, and others danced the mambo and the cha cha chá. These dancers embraced an idea of “Latin music” that was defined by musicians from Cuba and Puerto Rico.

Latino communities in the US are more diverse, however, than this Caribbean-centric definition of “Latin music” would suggest. Moreover, Latinos and Latinas have interacted with many other kinds of people to shape American music. Santana’s “Latin rock,” for example, was created on the West Coast by musicians from many different backgrounds. Mexican-born Carlos Santana loved the blues, and his guitar combined with Gregg Rolie’s organ to give their band a soulful sound. Conga player Mike Carabello, of Puerto Rican descent, shared his Tito Puente records with the band, and Nicaraguan Chepito Areas led the rhythm section on timbales. Drummer Michael Shrieve was white and bassist Dave Brown was African American. The Santana band was one of several multi-ethnic Bay Area bands—including Azteca, Malo, and Tower of Power—that integrated Latin music, rock, blues, jazz, and funk in the 1970s.

*****

“La Bamba,” Ritchie Valens (1958)

“La Bamba” is a traditional son jarocho from Veracruz that young Ricardo Valenzuela heard at family gatherings. When he got a contract with Del-Fi records (using the name Ritchie Valens) he recorded a doo wop song called “Donna,” and put “La Bamba” on the B side as a novelty. His version of “La Bamba” included some “Latin” touches, like a cha cha chá rhythm on the wood block, but it was the rock-and-roll energy and the whimsical chorus, “bam-ba, bamba,” that made it an unexpected hit with teenagers all over the country. Despite his untimely death in a plane crash at the age of nineteen, Ritchie Valens inspired a generation of Mexican American rockers, including Rosie and the Originals, Cannibal and the Headhunters, the Premiers, and Thee Midniters. Their music became known collectively as the “Eastside sound,” named for the Mexican American neighborhood of East Los Angeles.

“La Bamba” is a traditional son jarocho from Veracruz that young Ricardo Valenzuela heard at family gatherings. When he got a contract with Del-Fi records (using the name Ritchie Valens) he recorded a doo wop song called “Donna,” and put “La Bamba” on the B side as a novelty. His version of “La Bamba” included some “Latin” touches, like a cha cha chá rhythm on the wood block, but it was the rock-and-roll energy and the whimsical chorus, “bam-ba, bamba,” that made it an unexpected hit with teenagers all over the country. Despite his untimely death in a plane crash at the age of nineteen, Ritchie Valens inspired a generation of Mexican American rockers, including Rosie and the Originals, Cannibal and the Headhunters, the Premiers, and Thee Midniters. Their music became known collectively as the “Eastside sound,” named for the Mexican American neighborhood of East Los Angeles.

New generations of Los Angeles-based Chicano musicians built on the legacy of the Eastside sound, blending diverse styles. In the 1970s Los Lobos delved deeper into Mexican folk music and instruments and eventually combined them with rock and blues. In the 1980s singer Alice Bag (Alicia Armendariz) staked out a place for women in punk music. In the 1990s Zack de la Rocha mixed heavy metal with rap as the lead singer for Rage Against the Machine. In the 2000s the band Quetzal organized cross-border collaborations with musicians from Veracruz, helping to inspire a community arts movement that brought things full circle, with Mexican American youth singing, playing, and dancing “la bamba” in participatory fandangos.

*****

“Bang Bang,” Joe Cuba Sextet (1966)

This song mirrors the mixture of Latino and African American youth that crowded the dance floors of high school gymnasiums in Brooklyn, Harlem, and the South Bronx in the 1960s. A piano montuno combines with a steady clap on the backbeat, while singers Cheo Feliciano and Jimmy Sabater trade lyrics in Spanish and English, and make references to Caribbean and African American foods. “Bang Bang,” which reached national audiences and made Billboard’s Hit Parade, is an example of Latin boogaloo, a style that was all the rage in New York in the mid-1960s.

*****

“La Murga,” Willie Colón (1971)

By the late 1960s enthusiasm for the boogaloo waned, but its boundary-crossing and unifying spirit lived on in salsa. This song by Nuyorican bandleader Willie Colón and singer Hector Lavoe, with its memorable trombone line, borrowed rhythms from Panamanian carnival music to create a novel sound.

By the late 1960s enthusiasm for the boogaloo waned, but its boundary-crossing and unifying spirit lived on in salsa. This song by Nuyorican bandleader Willie Colón and singer Hector Lavoe, with its memorable trombone line, borrowed rhythms from Panamanian carnival music to create a novel sound.

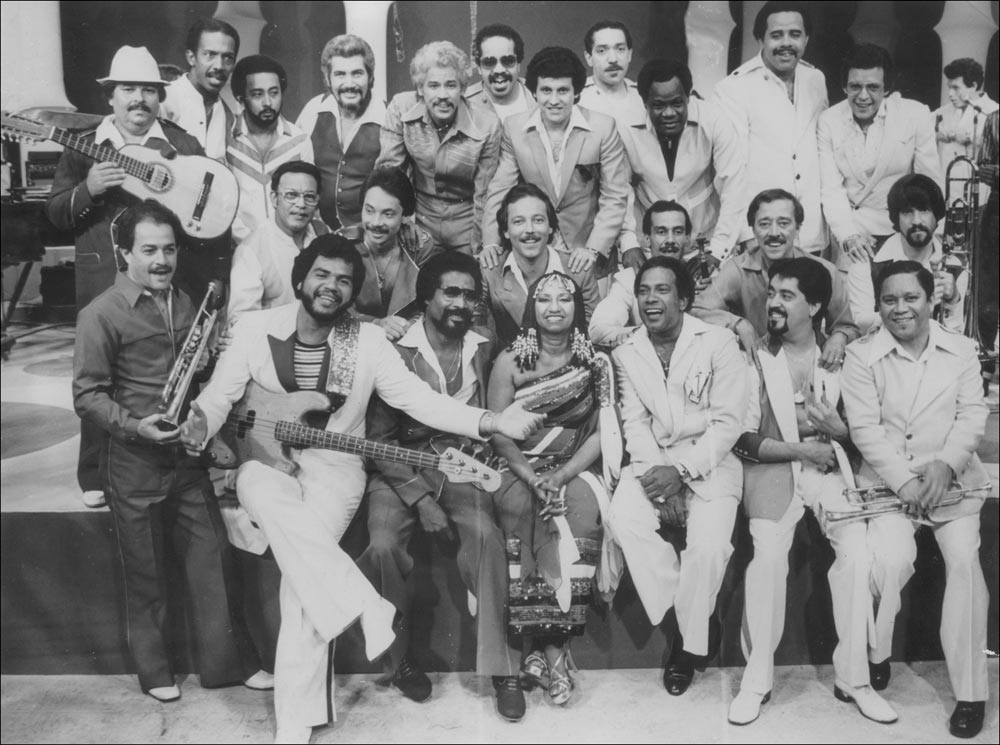

“Salsa” was a name the Fania record label chose to promote up-and-coming bands in New York and Puerto Rico, including those of Johnny Pacheco, Willie Colón, Bobby Valentín, Eddie Palmieri, and singers such as Hector Lavoe, Rubén Blades, Ismael Rivera, and Cheo Feliciano. One of salsa’s attractions was its celebration of urban working-class culture, as epitomized in the 1971 Fania All Stars concert film, Our Latin Thing, which resonated throughout Latin America. While Celia Cruz, the “Queen of Salsa,” saw salsa as a modern form of the music from her native Cuba, others understood it as something new and different. “I would say that salsa is a concept more than anything else,” says Willie Colón, “It’s a concept of inclusion.”[1]

*****

“Bidi Bidi Bom Bom,” Selena Quintanilla (1995)

A concept of inclusion is also evident in this song, which blends a reggae guitar strum, R&B vocal inflections, and a rock guitar solo with the rhythm of cumbia. Cumbia is a style that originated in Colombia in the 1940s, but by the 1950s Mexicans had made it their own. As early as the 1960s bands in Texas also began to play cumbia, and by the 1980s it was one of the most popular rhythms in Tejano music.

Tejanos also love to dance the polka, which was introduced in Northern Mexico and Texas by German and Czech immigrants in the nineteenth century. Polkas recorded by accordionist Narciso Martínez in the 1930s were an early model for the conjunto tejano, an iconic working-class dance ensemble that includes bass, drums, and bajo sexto along with accordion.

Rooted in regional traditions, Tejano music has also been shaped by national trends such as jazz, rock and roll, and country. For example, the “West Side sound” in San Antonio was a vibrant R&B scene in the 1960s that paralleled Los Angeles’s Eastside sound and produced nationally recognized bands like Sunny and the Sunliners. “Before the Last Teardrop Falls,” the 1975 country music hit by Freddy Fender (born Baldemar Huerta), included a verse in Spanish.

By the 1980s many threads of Texas Mexican musical taste came together in the genre known simply as “Tejano.” Centered in San Antonio, the Tejano music industry produced Spanish language songs by Laura Canales, La Mafia, Mazz, and other bands that saturated Texas radio, and were also popular across the border in Mexico. Selena was Tejano music’s biggest star. In 1995 she gave her last concert at the Houston Astrodome, where she opened with a medley of disco hits.

*****

“Conga,” Miami Sound Machine (1985)

“Conga” was the first of several hits by the Miami Sound Machine, fronted by Cuban American singer Gloria Estefán and led by her husband, Emilio. The song’s use of synthesizers and a steady dance beat was similar to Latin freestyle, a disco-inspired club music that started in New York with bands like Lisa Lisa and Cult Jam. Emilio Estefán combined this with prominent Afro-Cuban percussion and piano montunos to create the “Miami sound.”

Compared to the Eastside sound, salsa, or Tejano, the Miami sound was less grounded in a local community history, but its success signaled the growing influence of Latinos in mainstream commercial music. By the 1990s most of the major record labels had relocated their Latin music divisions to Miami, where the Cuban American business community was attuned to Spanish-language markets. As a producer for Sony Latin Music, Emilio Estefán recruited talented singers from different places—Marc Anthony and La India from New York, Ricky Martin from Puerto Rico, Shakira from Colombia—and shaped their sound for an international audience.

*****

“Despacito,” Luis Fonsi and Daddy Yankee (2017)

How did this Spanish-language song top the Billboard Hot 100 chart for a record-tying sixteen weeks straight? Good songwriting and production helped, and a version recorded with Justin Bieber helped it cross over to English-language audiences. But the ground for the song’s success was laid by the expanding popularity of reggaetón.

How did this Spanish-language song top the Billboard Hot 100 chart for a record-tying sixteen weeks straight? Good songwriting and production helped, and a version recorded with Justin Bieber helped it cross over to English-language audiences. But the ground for the song’s success was laid by the expanding popularity of reggaetón.

Reggaetón, which features spoken word over a distinctive “dem bow” beat[2] (first heard here at the chorus), has roots in different places. In the South Bronx, Puerto Rican youth participated in the street culture of hip hop in the 1970s, where they rapped, danced, and DJ’d. Meanwhile Jamaican DJs invented dance hall music, with their own style of rapping over records. Before long Panamanian youth created a version of dance hall in Spanish, called “reggae en español.” These styles converged in the “underground” music scene in San Juan, Puerto Rico, in the 1990s and turned into reggaetón. The first reggaetón song to get play on English language radio, “La Gasolina,” was recorded in 2004 by Daddy Yankee, presaging his even bigger success with “Despacito” thirteen years later.

*****

Where the next big thing in US pop music will come from we cannot know, but we know that Latino and Latina artists in every generation help renew our music, injecting it with fresh sabor and a dynamic vision of America.

Selected Bibliography

Berríos-Miranda, Marisol, Shannon Dudley, and Michelle Habell-Pallán. American Sabor: Latinos and Latinas in US Popular Music. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2018.

Flores, Juan. Salsa Rising: New York Latin Music of the Sixties Generation. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016.

Glasser, Ruth. My Music Is My Flag: Puerto Rican Musicians and Their New York Communities, 1917−1940. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995.

Loza, Steven. Barrio Rhythm: Mexican American Music in Los Angeles. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1993.

Pacini Hernandez, Deborah. Oye como va!: Hybridity and Identity in Latino Popular Music. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2010.

Paredes, Américo. With His Pistol in His Hand: A Border Ballad and Its Hero. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1958.

Peña, Manuel. The Texas-Mexican Conjunto: History of a Working-Class Music. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1985.

Reyes, David, and Tom Waldman. Land of a Thousand Dances: Chicano Rock ’n’ Roll from Southern California. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1998.

Rivera, Raquel Z. New York Ricans from the Hip Hop Zone. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003.

Roberts, John Storm. The Latin Tinge: The Impact of Latin American Music on the United States. New York: Oxford University Press, 1979; repr. 1999.

San Miguel, Guadalupe. Tejano Proud: Tex-Mex Music in the Twentieth Century. College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2002.

[1] Colón, Willie. October 2006 interview by Marisol Berríos-Miranda, New York. Experience Music Project archives.

[2] The “dem bow” rhythm gets its name from a 1990 song by Jamaican dance hall artist Shabba Ranks.

Marisol Berríos-Miranda and Shannon Dudley are married and are professors of ethnomusicology at the University of Washington. Berríos-Miranda has written numerous articles on salsa music. Dudley’s publications on Caribbean music include Music From Behind the Bridge: Steelband Spirit and Politics in Trinidad and Tobago (Oxford University Press, 2008). The two are co-authors, along with Michelle Habell-Pallán, of American Sabor: Latinos and Latinas in US Popular Music (University of Washington Press, 2018), a project that began as a bilingual museum exhibit that toured eighteen cities in the United States and Puerto Rico from 2007 to 2015.