Amateurism and Jim Thorpe at the Fifth Olympiad

by Kate Buford

Thorpe’s deception and subsequent confession deals amateur sport in America the hardest blow it has ever had to take and disarranges the scheme of amateur athletics the world over.

New York Times, January 28, 1913

The early years of the twentieth century were a dynamic, often chaotic time for the emerging phenomenon of sports in America. With the exception of baseball, which had its modern form in place by 1900, rules and organizations were formed and reformed year by year. Basketball was brand new, invented in 1891. Football was strictly a collegiate game dominated by the northeastern Big Three—Yale, Harvard, and Princeton. Professional football was deemed the "reptile sport" because its few and mainly lower-class players were paid. The ideal of the "pure amateur"—the pervasive ethos of the new American industrial elite and the aristocracy of Britain and Europe—was the athlete who played for the love of sport and not money.

A misreading of ancient Greek history by Victorian scholars had created the myth that the first Olympians competed for no financial gain or prize. The word "amateur" does not, in fact, exist in ancient Greek; it is a French word derived from the Latin amare, to love. The myth justified the cautionary view that when the ancient Games had "degenerated" into professional events, it had been a key sign of the end of the great Greek civilization.

Amateurism was in fact a ruthless standard meant to keep the lower, laboring classes out of sports. Only athletes with independent means of support could afford to compete. But amateurism was also the means to a bigger end for the wealthy class. It secured their control of the play, prestige, and money from the emerging sports universe.

The revival of the ancient Greek Olympic Games in 1896 was the most organized and famous expression of this amateur ethos. A French baron, Pierre Frédy de Coubertin, founded the modern Olympic movement in part as a way to inject the authentic ancient Greek ideal of a sound mind in a sound body into modern nations in danger, he believed, of becoming physically unfit and thus morally soft. By 1912, for the fifth modern Olympiad in Stockholm, each competitor had to sign an entry form affirming that he or she was an amateur—"one who has never" competed for money or prize, competed against a professional, taught in any branch of athletics for payment (i.e., been a coach) or "sold, pawned, hired out, or exhibited for payment" any prize.

The most prestigious athletic events of the modern Olympics were the classic track-and-field sports originated by the Greeks to showcase the glory of the fit human body. The five-event pentathlon and the ten-event decathlon were the supreme tests of the complete athlete. Running, pole vaulting, hurdles, high and long jumps, javelin and discus throws, and putting the shot were meant to "reconcile the irreconcilable: speed and resistance, dynamism and statism, strength and lightness, power and relaxation" according to French track expert Robert Pariente.

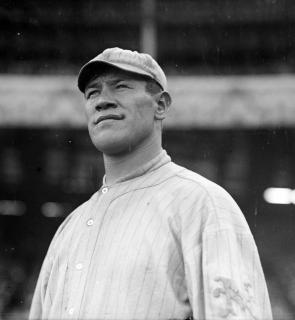

When Jim Thorpe, an American Indian from Oklahoma, triumphed in the pentathlon and decathlon by huge margins, the achievement surprised all. Americans were generally derided as specialists who trained too hard. They were not expected to win these multi-events in Stockholm. Sweden’s King Gustav V, placing the traditional laurel crown on Thorpe’s head for the decathlon gold medal victory, called him "the most wonderful athlete in the world."

Thorpe had already captured the imagination of Americans with his stellar performance on the 1911 Carlisle (Pennsylvania) Indian Industrial School football team, leading it to victories over powerhouses such as Harvard and the University of Pennsylvania. Since the first game in 1869, American collegiate football had developed into the athletic crucible of the nation’s elite. Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson passionately extolled its "moral qualities." Four months after winning the two Olympic gold medals, Thorpe was the star of Carlisle’s remarkable upset win against the Army team at West Point, the most stunning in the school’s 12-1-1 season of 1912. Barely more than two decades after the massacre at Wounded Knee, the Indian School’s football victories inspired both admiration and animosity. Thorpe, the team captain and the world’s most famous Olympian, seemed too good to be true.

The turning point in Thorpe’s life and, by extension, in American and international sports, came fast on the heels of his athletic success. In late January 1913, a scoop in the Worcester Telegram revealed that Thorpe had played professional minor league baseball in North Carolina during the summers of 1909 and 1910. He was thus not only a "professional," he had covered it up to compete as an amateur in Stockholm.

Newspapers across the country and around the world followed every twist of the story. It was a bona fide international sports scandal—one of the first and most notorious. After a series of snafu-ridden Olympiads, the Swedish Olympics had been the first well-run games of the modern era. Thorpe’s remarkable performance had set a standard of achievement and newsworthiness that put the Olympic movement on a much more solid footing. The reaction and analysis went on for months. The International Olympic Committee, based in Switzerland, let the American organizers deal with the Thorpe "peccadillo," as de Coubertin called it. Though the baron’s private view of amateurism was more nuanced than most, he needed the financial and organizational backing of his aristocratic colleagues on both sides of the Atlantic to ensure the future of the games.

Thorpe’s role in the scandal was complicated. He had left the Carlisle Indian School in 1909 to play minor league baseball for pay and, he hoped, do well enough to move into the major leagues. The only sport at the time with an organizational structure of leagues and teams, and the relative financial security that came with it, was professional baseball. Playing ball during the summer attracted many "college boys." Most of them changed their names to protect their amateur status when they returned to school in the fall. Thorpe did not. In his mind he had turned professional.

Thorpe returned to Carlisle in 1911 at the request of his football and track-and-field coach, Glenn S. "Pop" Warner. Thorpe had been an outstanding track-and-field athlete in 1909 and Warner wanted to prepare him for the Stockholm Olympics. Thorpe trusted Warner to figure out the amateurism issue. Warner knew about Thorpe’s professional baseball summers, but denied any such knowledge when the scandal broke. To do so would have risked his own rising stature in American sports, largely earned as a result of Thorpe’s football and Olympic successes. Warner wrote the famous letter to the Amateur Athletic Union in Thorpe’s name. In the letter, the twenty-six-year-old athlete said he was "simply an Indian schoolboy" who knew no better about the rules of amateurism and hoped the AAU and "the people" would not be too hard in judging him.

But the AAU was very hard indeed and rushed to repair the damage to America’s new status as the world’s leader in sports. The Swedish Olympic Committee’s 1912 rules stipulated that all challenges to the Games had to be presented within three months of the event in question. That time was long past. The AAU and the American Olympic Committee (virtually the same organization at the time) ignored the rule. There was no system of arbitration or redress in place. "Such a case has not occurred before," the Revue Olympique commented in March 1913, "and a jurisprudence will have to be established."

Five days after the story broke Thorpe was stripped of his amateur status and ordered to return his two gold medals and trophies to the AAU for shipment back to Sweden. The gold, silver, and bronze medal winners and records were adjusted accordingly. "In the history of amateur athletics," reported one newspaper, "there is no case to parallel the rise to fame of the . . . Indian and his even more meteoric descent to the ranks of the professionals."

"The people," however, embraced Thorpe’s story with a fervor and tenacity that would persist for decades even as new sports heroes surpassed him, their fame enhanced by the advent of radio in the 1920s and television in the 1950s. Thorpe was seen as the outsider wronged by a snobbish elite invested in preserving sports for the privileged few. What did baseball have to do with track and field? A Harvard or Yale college student would have been handled differently, protected. At a time when immigrant Jews, Irish, Italians, and others were second-class citizens and African Americans were barred from white sports almost entirely, the summary disposal of this outstanding Native American athlete was bitter proof that an equal playing field did not exist.

Thorpe’s identity as an American Indian, though with almost half-white ancestry, was especially significant. He was not an American citizen, but a ward of the nation. The white conquest of the continent had been completed by 1890. Memories of the so-called Indian Wars were fresh. Crude stereotypes of the ignorant, violent savage were encouraged by the Wild West shows popular at the time, as well as by the dime novels read by millions. With sports glorified as tests of superior mental and physical worth and Indians generally considered to be in danger of extinction, Thorpe’s astonishing performance against the best white athletes upended many deeply held assumptions. The unique combination of his extraordinary athletic skill, his Indian identity, and the shabby treatment of him by the guardians of amateurism created a kind of folk-hero mystique. In a century that would be marked by increasing political, social, and sporting equality, he became a touchstone.

The more astute observers of the Thorpe scandal at the time derided the sham of amateurism and predicted that professionalism would be the athletic paradigm of the future. Yet it would take the better part of the rest of the century for the idea of amateurism to die. The word "amateur" would indeed become a more derogatory term, meaning someone who is not good at what he does (e.g., "amateur hour," "a bunch of amateurs," etc.). "Professional," on the other hand, would come to mean expert, the person who works and practices until he masters a skill and is paid and rewarded for his effort.

Thorpe turned professional in 1913. In 1920, he was elected president of the organization that became, two years later, the National Football League. By the time his athletic career ended in 1928 he had played major league baseball and boosted the status of professional football out of its sandlot beginnings. Thorpe died in 1953, but the popular anger at the injustice of his Olympic story only grew. His amateur status was reinstated by the AAU in 1973. In 1982, after a vigorous campaign by his family, athletes, and US political leaders, the International Olympic Committee agreed to list him as a co-winner of the 1912 pentathlon and decathlon. The adjusted medal allocations of 1913 were not changed. The IOC refused to enter Thorpe’s remarkable scores in its official record. There are, thus, two official gold medal winners of each multi-event, a sports absurdity.

Jim Thorpe was perhaps the greatest all-around athlete of modern times. His Olympic story, one of the earliest and most dramatic turning points in sports history, remains unresolved.

Kate Buford is the author of Burt Lancaster: An American Life (2000) and Native American Son: The Life and Sporting Legend of Jim Thorpe (2010).