Welcome To The Second Issue of History Now

Students often ask: How do historians know what happened in the past? How do they know what Frederick Douglass said about slavery, what Abigail Adams thought about American independence, or what happened at Sutter’s mill? As scholars and teachers, we know that primary sources are the building blocks, the "stuff" of history.

Official government documents, political speeches, wills, newspapers, diaries, and letters are just a few of the sources we can draw upon to reconstruct an historical era or an individual life. We can also turn to paintings, political cartoons, and in later decades, photographs and film footage. Borrowing techniques from other disciplines such as archaeology and anthropology, historians can reconstruct the material world of seventeenth-century Jamestown colonists and the family structures of eighteenth-century enslaved men and women of the Chesapeake. Using the technology of the twentieth century, we can computerize hundreds, even thousands, of tax records or probate court documents and discover patterns that reveal economic differences among residents of a nineteenth-century city or the steady growth of a consumer culture in the early Republic.

In addition, the tools people leave behind are clues to the lives of women and men who did not have the time or the skill to record their thoughts and experiences in letters. Slave ship logs provide documentation of journeys taken, while the oral histories passed from one generation to another preserve life stories as valid as those preserved in diaries. Modern-day census data, tax returns, business audits, architectural drawings, department store catalogues, clothing, jewelry -- even your students’ report cards and term papers -- these will all be primary sources for future historians hoping to understand our society and culture.

Increasingly, teachers at every level are bringing primary sources into the classroom. Working with these sources, students learn how to piece together a story of the past and how to become active investigators and analysts, rather than passive listeners to a story. In reading a slave’s account of her escape to freedom or a soldier’s account of a World War I battle, students develop their capacity to empathize with the world views of people distant from them in both time and space.

Because we believe that bringing the "stuff" of history into the classroom is so important, HISTORY NOW devotes its second issue to the examination of primary sources. Our contributing scholars focus on four different types of primary sources and apply them to the task of looking at the history of enslaved African Americans. Their essays tell us not only what these types of sources reveal but also how to evaluate their validity and how to use them effectively. David Blight, at Yale University, writes about slave narratives as both an historical source and a literary genre. Eric Foner, at Columbia University, looks at the Reconstruction Amendments and the social history behind them. Douglas R. Egerton, from Le Moyne College, explains the importance of looking at artifacts enslaved people left behind. And Annette Gordon-Reed, from New York Law School, discusses the intersection of oral history and documentary evidence.

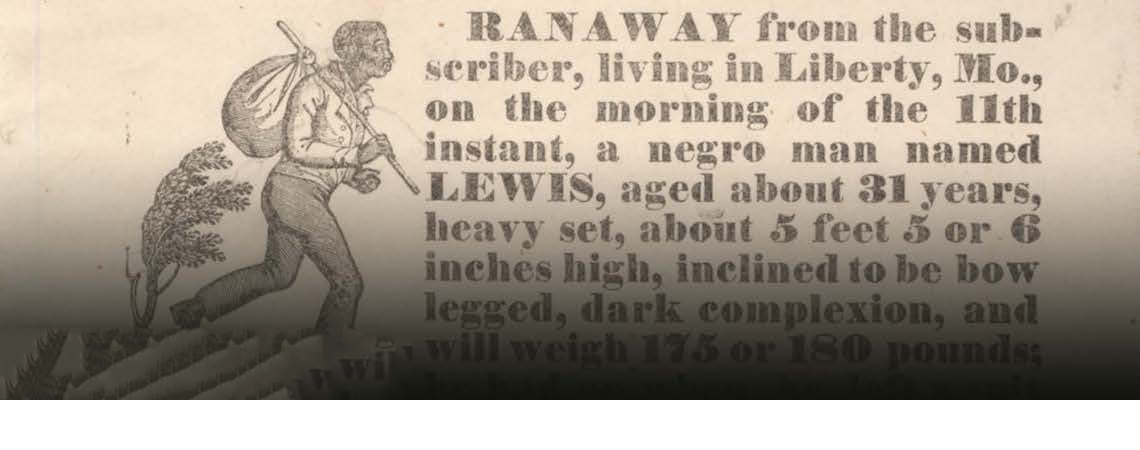

We have provided four lesson plans from master teachers outlining ways in which to use primary sources at the fifth grade, middle school, and high school levels. The lesson plans include printable primary sources such as abolitionist broadsides and runaway slave notices, and links to outside resources that provide a host of ideas for your classroom. Our interactive map of the United States will give students a chance to examine primary sources relating to slavery from every region of the country, and our archivist once again gives resource suggestions for further study.

We look forward to hearing from you at our "Digital Drop Box," where you can submit questions, comments, and stories from your classroom.

Sincerely,

Carol Berkin Angelo Angelis

Editor, History Now Associate Editor

Carol Berkin is Professor of History at Baruch College and The Graduate Center, City University of New York. She is the author of several books including Jonathan Sewall: Odyssey of an American Conservative, First Generations: Women in Colonial America, A Brilliant Solution: Inventing the American Constitution, and Revolutionary Mothers: Women in the Struggle for America's Independence.