From the Editor

During the war for independence, the first major fundraising drive in American history was mounted in Philadelphia. As the two Pennsylvanians who conceived of the drive knew, this effort to raise funds for Washington’s army would require careful planning and organization. They got to work. They assigned three or four volunteers to cover each of the wards or neighborhoods of Philadelphia and sent them door to door to solicit funds, including someone to collect and record the contributions they received. They sent copies of their organizational plan to friends and relatives across the newly forming states. And, when their fund drive was challenged, they composed a powerful defense of it in the name of patriotism and the struggle for independence. Their success was remarkable; General Washington received over $300,000 to aid his ragtag army.

Who were these creative, efficient, and determined Americans? Two genteel matrons, Sarah Franklin Bache and Esther DeBerdt Reed. Together with their determined volunteers, these women broke the rules that said decent women should not take to the streets without a male escort and never talk to a man unless they had been formally introduced. Undaunted, they visited poor as well as wealthy neighborhoods and knocked on strangers’ doors, asking for contributions. They did this, they said, because, like their husbands, brothers, fathers and sons, they were "born for liberty."

Like Bache and DeBerdt Reed, American women of later eras ignored social conventions in order to serve the public good, whether in philanthropy or elected and appointed office. In this issue of History Now, our contributors track the expanding arenas in which women "born for liberty" can make their mark. They explore the emergence of women as elected officials even before the Nineteenth Amendment, the role they continue to play in creating and directing philanthropic organizations, and the path they have taken as jurists that sometimes led to seats on the Supreme Court bench.

In "Women’s Leadership in the American Revolution," Rosemarie Zagarri argues that one of the most radical impacts of the Revolution was the politicization of women and the unleashing of their organization and literary talents as well as their political voice. She points out that leaders in the movement for independence needed to appeal to new constituencies, including white women. The results were dramatic: once criticized for any political comment, these women were now encouraged by ministers, political figures, and newspaper editors to speak up and act as defenders of liberty. Zagarri uses three examples to demonstrate the entrance of women into the political and public sphere: the literary works produced by Mercy Otis Warren of Massachusetts; the "Tea Party" held by the women of Edenton, North Carolina; and the fund raising phenomenon by Esther DeBerdt Reed’s Ladies Association of Philadelphia. Each of these examples demonstrates the major contributions women made the revolutionary struggle, but, as Zagarri reminds us, we must not forget the thousands of other women who also contributed to our national independence. These women rallied political sentiment, mobilized popular resistance, and made sacrifices that were critical to American success. They were, Zagarri declares, "political ciphers no more."

In "Her Hat Was in the Ring: How Thousands of Women Were Elected to Political Office Before 1920," Wendy E. Chmielewski reminds us that women were elected to local offices, from county treasurers, to school board members, to justices of the peace and town council members, decades before the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment. In fact, some 5,000–6,000 women held elective office across the United States between 1850 and 1920. These women had not been shy about campaigning; they attended party conventions, gave interviews in local newspapers, handed out campaign literature, produced campaign songs and slogans, and gave public speeches. Where they could, these female candidates sought support from temperance, health reform, and feminist organizations. Single or married, these women challenged local customs and social norms to demonstrate that they were born for leadership as much as for liberty.

In "How Women Legislate," Sue Thomas takes up several important questions about women in government. Among them are: Do women legislate differently than men? And if so, does it matter? Thomas cites research that shows that women do indeed have "distinctive points of view" about how to serve their city, state, or country. Women elected to office tend to be more liberal than men, and they are more likely to support social issues that affect their gender, including affordable child care, equal pay, and the prevention of violence against women. Although they are more attuned to these women’s issues, they are also involved in decision-making about foreign policy, infrastructure, and the economy. Thomas’s research finds that women’s leadership style differs from that of men. Women foster cooperation rather than competition; they work to build consensus; and they engage in team-building. They seem to avoid partisan infighting, preferring to pursue solutions to problems rather than simply win an argument. Of course, Thomas reminds us, these characteristics are not universal, and factors such as race, ethnicity, and sexual orientation complicate the generalizations about women legislators.

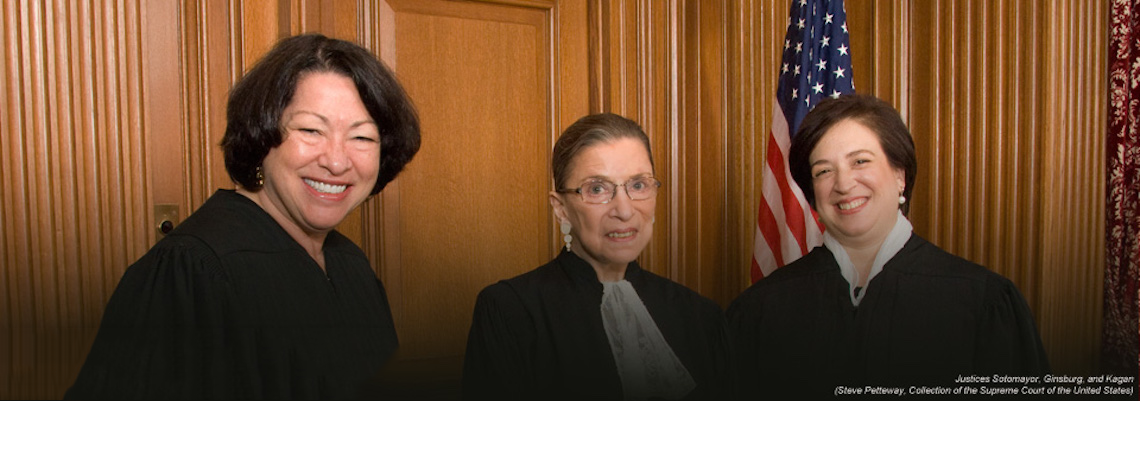

In her essay, "Women and the United States Supreme Court," Julie Silverbrook looks at the women whose ambition and talent led them into the courtroom and onto the judicial bench. From wealthy colonial women like Margaret Brent of Maryland, to a freed black woman named Lucy Terry Prince, seventeenth- and eighteenth-century women argued for their rights before local judges. In the nineteenth century, women fought for admission to law schools and to the bar. Since 1880, almost 1500 women have argued before the US Supreme Court. But, as Silverbrook points out, women also aspired to judgeships, and four of these women reached the the most prestigious position our judicial system offers: a seat on the Supreme Court. In this essay, Silverbrook offers brief histories of the careers of Sandra Day O’Connor, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Sonia Sotomayor, and Elena Kagan.

As Harriet Karr-McDonald demonstrates in "Creating Opportunity: My Fight for Social Justice and Advice for Young Women Today," her personal account of her role as co-founder of the Doe Fund’s Ready, Willing & Able transitional work program in New York City, women continue to demonstrate their leadership abilities in the philanthropic world. In telling her own story, Karr-McDonald recounts how she came to focus her talents on helping the homeless of New York City prepare for the paid workplace. For her, the personal rewards have been well worth the effort that went into establishing this unique—and successful—program. As she puts it, "there is no better life than one centered around helping others"—a sentiment shared by women like Sarah Bache and the many women reformers of the nineteenth century who sought to improve the lives of the poor, the imprisoned, and the immigrants who came to our country.

Our digital feature in this issue is a compilation of videos featuring presentations by noted scholars in the field of women’s history, available on the Gilder Lehrman Institute website, https://www.gilderlehrman.org/multimedia/albums/women%E2%80%99s-world.

And, as always, this issue contains lesson plans that can be adapted by you to your own classroom.

We hope that this issue will serve you well as we enter March, Women’s History Month.

![]()

Carol Berkin

Editor

From the Archives

Past Issues of History Now

Women’s Suffrage: History Now 7 (Spring 2006)

America’s First Ladies: History Now 35 (Spring 2013)

Essays

“A Poem Links Unlikely Allies in 1775: Phillis Wheatley and George Washington” by James G. Basker

“Eleanor Roosevelt as First Lady” by Maurine Beasley

“Women in American Politics in the Twentieth Century” by Sara Evans

“African American Women in World War II” by Maureen Honey

“Nineteenth-Century Feminist Writings” by Anne Firor Scott

“The Seneca Falls Convention: Setting the National Stage for Women’s Suffrage” by Judith Wellman

Featured Primary Sources

Phillis Wheatley’s poem on tyranny and slavery, 1772

Lucy Knox on the home front during the Revolutionary War, 1777

Martha Washington on life after the Revolution, 1784

Lydia Maria Child on women’s rights, 1843

The service of Medal of Honor recipient Dr. Mary Walker, 1864

The women’s rights movement after the Civil War, 1866

Susan B. Anthony on suffrage and equal rights, 1901

Amelia Earhart to her former flight instructor, Neta Snook, 1929