Douglass and Lincoln: A Convergence

by James Oakes

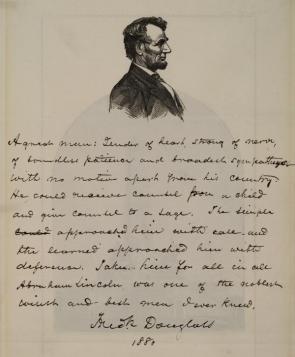

In 1880, Osborn Oldroyd invited Frederick Douglass to write something for a collection of tributes to Abraham Lincoln, published two years later as The Lincoln Memorial: Album-Immortelles. Douglass was uncharacteristically brief, but in a mere sixty-eight words he captured many of the elements of character that he believed made Lincoln “a great man.” Lincoln was tender but strong, patient, a man of broad sympathies, and above all a patriot. At once unpretentious and impressive, Lincoln was, to Douglass, “one of the noblest wisest and best men I ever knew.”

In 1880, Osborn Oldroyd invited Frederick Douglass to write something for a collection of tributes to Abraham Lincoln, published two years later as The Lincoln Memorial: Album-Immortelles. Douglass was uncharacteristically brief, but in a mere sixty-eight words he captured many of the elements of character that he believed made Lincoln “a great man.” Lincoln was tender but strong, patient, a man of broad sympathies, and above all a patriot. At once unpretentious and impressive, Lincoln was, to Douglass, “one of the noblest wisest and best men I ever knew.”

Douglass’s admiration for the sixteenth president was by then well-known. As far back as 1865 he had described Lincoln as “the black man’s president” and declared that whatever the assassination might have meant for White Americans, for African Americans it was “an unspeakable calamity.” A decade later, in his longest and most thoughtful evaluation, given at the dedication of the Freedmen’s Monument in Washington, DC, Douglass described Lincoln as a “statesman” who, measured “by the sentiment of his country,” had been a “swift, zealous, radical, and determined” supporter of emancipation. When an idealistic radical like Frederick Douglass falls into such effusions about a cagey and conservative politician like Abraham Lincoln, explanations are in order.

Douglass had not always been so kindly disposed. “I cannot support Lincoln,” he wrote in 1860, vowing to cast his vote for the Radical Abolitionist presidential candidate. Well into Lincoln’s presidency, Douglass found nothing but fault. The government, Douglass concluded in August of 1861, “has resolved that no good shall come to the Negro from this war.” A year later, still waiting impatiently for word of an emancipation proclamation, Douglass denounced Lincoln as “a genuine representative of American prejudice and Negro hatred.”

When the proclamation came, Douglass’s attitude toward Lincoln inevitably softened. To be sure, there were new fights to be fought, new struggles to be engaged: Black and White soldiers should be treated equally, and Black men should be allowed to vote. But it was different, now, and Douglass had enough faith in Lincoln to tell him these things directly. The two men met for the first time on August 10, 1863. The radical spoke his piece, the President stood his ground, and Douglass left the meeting deeply impressed by Lincoln. “Wise, great, and eloquent,” Lincoln would “go down to posterity, if the country is saved, as Honest Abraham.”

Douglass was impressed, but he was not fully convinced. In early 1864, he cast his lot with a small faction of Republicans who hoped to replace Lincoln with a more reliably radical presidential candidate. It was during these months that Douglass, writing privately to an English abolitionist, made some of his harshest remarks about Lincoln. The President’s policy, Douglass complained, is “Do evil by choice, right from necessity.” That was the worst of Douglass’s criticism, but it was also the last of it.

In the 1864 election, Lincoln easily put down his radical rivals, the Democrats spilled forth a Niagara of racial demagoguery, and Douglass threw himself into the campaign for the President’s re-election. In the midst of it all, when things looked grimmest for Lincoln, he invited Douglass back to the White House for a second visit in August 1864. This time, Douglass realized the President was irreversibly committed to emancipation and that Lincoln himself was utterly lacking in common racial prejudices. “In his company I was never in any way reminded of my humble origin, or of my unpopular color.” Indeed, the two men genuinely seemed to like each other. They met one last time, at Lincoln’s second inaugural, where the President publicly embraced “my friend Douglass” as a man whose opinion he valued and whose company he enjoyed. A few weeks later Lincoln was dead.

But Douglass lived on, and for the next forty years, his reflections on the sixteenth president were haunted by the question, what if Lincoln had lived? Douglass’s answer was inevitably shaped by the fact that he himself had changed his mind about Lincoln. This was partly a matter of personality—although they met only three times, the more Douglass saw of Lincoln the more he liked him. Lincoln, too, had changed. He had been radicalized by the war, and this had made him more attractive to Douglass. In turn, Douglass had come to understand the power of mainstream politics and to appreciate what an astute politician like Lincoln could accomplish in a democracy where elected officials were responsible to an electorate that was rarely sympathetic to the demands of radicals like Frederick Douglass.

No doubt the assassination colored Douglass’s later views. Moreover, as Black southerners were subjected to an intensifying campaign of terror, as the freedoms won in war were whittled down by an uneasy peace and the political rights hammered into place during Reconstruction were sawed away, Douglass looked back wistfully at the legacy of Abraham Lincoln. This was neither nostalgia nor hazy retrospection. The two men had been converging for years, long before Lincoln’s assassination. Thereafter, the same person Douglass had once denounced as the mindless mouthpiece of pro-slavery racism came into clearer focus as a great politician and a great man.

Douglass lived a long and remarkable life. He had known many of the greatest reformers of his age. And yet, “take him for all in all Abraham Lincoln was one of the noblest wisest and best men I ever knew.” It had taken Douglass some time to reach that conclusion, but for that it was all the more heartfelt.

James Oakes is Graduate Humanities Professor and professor of history at the Graduate Center, The City University of New York. He is the author of The Radical and the Republican: Frederick Douglass, Abraham Lincoln, and the Triumph of Antislavery Politics (2007), winner of the Lincoln Prize.