Douglass, Lincoln, and the Civil War

by Chandra Manning

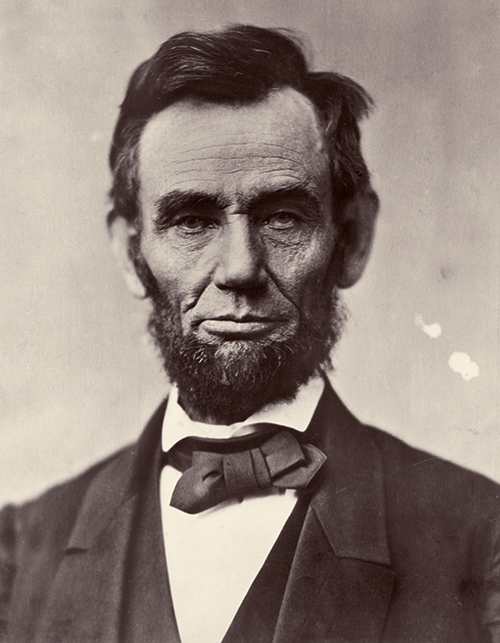

“Here comes my friend Douglass,” exclaimed President Abraham Lincoln in the East Room of the White House after delivering his Second Inaugural Address on March 4, 1865. As he grasped the hand of the distinguished abolitionist and orator Lincoln continued, “there is no man in the country whose opinion I value more than yours. I want to know what you thought of it.” In stately tones, Douglass told the President that the speech “was a sacred effort.” [1]

“Here comes my friend Douglass,” exclaimed President Abraham Lincoln in the East Room of the White House after delivering his Second Inaugural Address on March 4, 1865. As he grasped the hand of the distinguished abolitionist and orator Lincoln continued, “there is no man in the country whose opinion I value more than yours. I want to know what you thought of it.” In stately tones, Douglass told the President that the speech “was a sacred effort.” [1]

Lincoln’s second inauguration occurred four years into the Civil War, and in the address that Douglass praised so warmly, the re-elected president identified slavery as a “peculiar and powerful interest” which “all knew . . . was somehow the cause of the war.”[2] Slavery represented the single greatest source of wealth in the nation aside from land, powered the national economy, and until 1861, its proponents controlled the federal government. A close look at the evolving relationship between Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass lends insight into how the war dismantled slavery.

For President Lincoln, the goals of saving the Union and ending slavery were linked. A separate Confederacy would ensure the survival of slavery in the seceded states, just as a United States with slavery would continue to fracture over the contentious issue. Personally, Lincoln hated slavery. “If slavery is not wrong, then nothing is wrong,” he insisted.[3] But as president, his approach was cautious and legalistic, and at times seemed to prioritize the Union over abolishing slavery. For example, Lincoln believed that keeping Border States (states with slavery that did not join the Confederacy) in the Union was crucial to winning the war, so in his First Inaugural Address of March 1861 he stated that he had “no purpose, directly or indirectly, to interfere with slavery in the states where it exists.”[4]

For Frederick Douglass, the goal of ending slavery was paramount. Born in bondage in Maryland, Douglass grew up relatively “privileged” compared to most American slaves, yet slavery still stole almost everything from him: family (he never knew his father and his mother died when he was seven), opportunity (as a slave, he was forced to labor for the enrichment of others), and basic human rights (he was beaten, starved, and neglected). He fought back by learning to read. At age twenty, he ran away. At first he settled with his wife in New Bedford and made a living as a ship caulker, but soon he launched a career as an abolitionist orator, writer, and newspaper editor.

When war came, Douglass hoped the Union would “strike down slavery itself, the primal cause of that war.” As he saw it, immediate abolition offered “one easy, short and effectual way to suppress and put down the desolating war.”[5] Lincoln’s cautious approach frustrated Douglass because it did not adequately combat the horrors of slavery and seemed to validate rather than challenge northern racism. Besides, the history of the 1840s and 1850s showed that compromise prolonged rather than resolved conflict by emboldening pro-slavery forces. Douglass’s frustration boiled over in a speech delivered July 4, 1862, in which he declared, “We have a right to hold Abraham Lincoln sternly responsible for any disaster or failure attending the suppression of this rebellion,” because of hesitancy to smash rebellion’s root cause immediately.[6]

Differences between Lincoln and Douglass arose from their contrasting backgrounds. Unlike Douglass, Lincoln had never been enslaved. A lawyer, statesman, and recipient of the blessings of liberty furnished by the US government, Lincoln nurtured a bedrock belief in law and in the American system of government. To him, the United States was the “last best hope of earth” for a self-governing republic dedicated to the well-being of its citizens. He remained staunchly committed to working within the political system to effect change.[7]

The winds of civil war eroded the men’s differences, revealing underlying similarities like hard marble below chalky soil. As Douglass frequently observed, both were self-made men, a quality so important to Douglass that he gave over fifty speeches on it.[8] Both had been deeply influenced in their youth by The Columbian Orator, a children’s reader of great speeches that endowed each with a belief in the power of language. Above all, both truly hated slavery despite their initially divergent strategies for ending it.

The two men met in person only three times. The first meeting occurred about two-and-a-half years into the war on August 10, 1863.

By then, the federal government’s policy on slavery had evolved considerably. From the first shots in 1861, enslaved men, women, and children ran to the Union Army and contributed their labor and local knowledge (perfect for spying) to the war effort. Confiscation Acts passed in August 1861 and July 1862 emancipated slaves who made it to the Army. Congress outlawed slavery in federal territories and the District of Columbia. The Emancipation Proclamation declared slaves in Confederate-held territories “forever free” as of January 1, 1863. Also in 1863, the Army did what Frederick Douglass had urged since the spring of 1861: admitted black men into the ranks of the Union Army. Past military age himself, Douglass served as a recruiter, but his sons, Charles and Lewis, fought; Lewis was wounded when his regiment, the Massachusetts 54th Infantry, stormed Fort Wagner in South Carolina.

Despite their courageous service, black soldiers were initially paid less than white soldiers, barred from officers’ ranks, and faced greater dangers because Confederates killed or enslaved black prisoners of war. Outraged, Douglass boarded a train from his home in Rochester, New York, to confront President Lincoln in person about these inequities.

When Douglass arrived at the White House, he presented his card and within minutes was invited into Lincoln’s office. There, the sprawling, disheveled president leapt to his feet, extended his hand, and said, “Mr. Douglass, I know you; I have read about you. . . . Sit down, I am glad to see you.”[9] Douglass criticized Lincoln’s statements in support of colonization of freedpeople outside the United States and objected to the treatment of black soldiers. He was heartened by Lincoln’s recent order retaliating against Confederates who killed or enslaved black prisoners of war, but wondered why it had taken so long to issue. Lincoln answered each charge by claiming that he had to wait for white public opinion to catch up, or risk backlash. Douglass was not entirely satisfied with the President’s answers, but he appreciated Lincoln’s “honesty and sincerity” and the complete equality with which Lincoln treated him.[10]

The second meeting took place on August 25, 1864. By that time, pay equity and other conditions for black soldiers had improved, and Lincoln was running for re-election on a platform of unconditional restoration of the Union and a constitutional amendment abolishing slavery. But the Union military effort bogged down. War weariness mounted, and Lincoln feared that his opponent, George McClellan, might win on an anti-war platform that would roll back emancipation.

Lincoln invited Douglass to the White House to ask for help. Douglass agreed to travel “beyond the lines of our armies, and urge the slaves to come within our boundaries,” where they would be emancipated.[11] The fall of Atlanta and Lincoln’s re-election in November rendered the plan unnecessary, but both men valued the visit as an opportunity for two strong thinkers to collaborate on a shared goal.

Douglass’s and Lincoln’s final meeting at the second inauguration in March 1865 happened just one month before Confederate forces surrendered and a mere forty-one days before Lincoln was assassinated. Learning of the President’s murder while at home in Rochester, Douglass delivered a spontaneous eulogy in which he quoted the Second Inaugural Address and identified Lincoln as “that great and good man, one of the noblest men to trod God’s earth,” thanks to whom “the nation is saved and liberty established forever.”[12] In December 1865, ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment abolishing slavery seemed to prove Douglass’s point.

But things were not so simple. Douglass always saw abolition as a first but not final step toward equal rights and full inclusion for African Americans. In later decades, successive steps proved halting. Douglass remained active in the Republican Party for the rest of his life, serving as Recorder of Deeds for the District of Columbia and US ambassador to Haiti. He fought vigorously for voting rights and equality before the law. Sometimes his efforts yielded fruit, such as the passage of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments, but prior to Douglass’s death in 1892, white supremacists recaptured southern state governments while white northerners, the federal government, and the judicial branch looked the other way at best, and colluded at worst. Douglass’s optimism and his estimation of Abraham Lincoln fluctuated. Sometimes, he called Lincoln “pre-eminently the white man’s President, entirely devoted to the welfare of white men,” while at other times he called him “emphatically, the black man’s President: the first to show any respect to their rights as men.”[13]

The Civil War made allies of Lincoln and Douglass, but it did not make them perfect or the same. Neither could single-handedly overcome intransigent American racism, but working within and through their differences allowed Douglass and Lincoln to do more together to destroy slavery than either could achieve on his own.

[1]Frederick Douglass, The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass, Written by Himself, Reprinted from the Revised Edition of 1892 (London: Collier-Macmillan, 1962), pp. 365–366.

[2] Abraham Lincoln, Second Inaugural Address, March 4, 1865.

[3] Abraham Lincoln to Albert Hodges, April 4, 1864.

[4] Abraham Lincoln, First Inaugural Address, March 4, 1861.

[5] Frederick Douglass, “How to End the War,” Douglass’ Monthly, May 1861, in Frederick Douglass: Selected Speeches and Writings, ed. Philip S. Foner (Chicago: Lawrence Hill Books, 1999), p. 448. Italics in original.

[6] Frederick Douglass, “The Slaveholders’ Rebellion,” July 4, 1862, Frederick Douglass: Selected Speeches and Writings, p. 502.

[7] Abraham Lincoln, Annual Message to Congress, Dec. 1, 1862.

[8] See, for example, Frederick Douglass, “Self-Made Men,” in John Blassingame and John McKivigan, eds., The Frederick Douglass Papers, Series One, Vol. 5, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2991), pp. 545–575,

[9] Douglass, Life and Times, p. 347.

[10] Frederick Douglass to George Stearns, August 12, 1863, quoted in James Oakes, The Radical and the Republican: Frederick Douglass, Abraham Lincoln, and The Triumph of Antislavery Politics (New York: Norton, 2007), pp. 210–217, and John Stauffer, Giants: The Parallel Lives of Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln (New York: Twelve, 2008), pp. 19–22.

[11] Douglass, Life and Times, pp. 358–359.

[12] Frederick Douglass, “Our Martyred President,” Rochester, NY, April 15, 1865 in Frederick Douglass Papers.

[13] “Oration in Memory of Abraham Lincoln, Delivered at the Unveiling of the Freedmen’s Monument in Memory of Abraham Lincoln, in Lincoln Park, Washington, D.C., April 14, 1876,” Frederick Douglass: Selected Speeches and Writings, p. 618; Frederick Douglass, June 2, 1865, Frederick Douglass Papers, Library of Congress.

Recommended Resources from the Author

Digital Resources

Frederick Douglass Papers at the Library of Congress

https://www.loc.gov/collections/frederick-douglass-papers/about-this-collection/

Frederick Douglass Papers

http://frederickdouglass.infoset.io/

Teaching with the Frederick Douglass Papers (Library of Congress): https://www.loc.gov/teachers/classroommaterials/connections/frederick-douglass/

Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress

https://memory.loc.gov/ammem/alhtml/malhome.html

Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln

https://quod.lib.umich.edu/l/lincoln/

For Further Reading

David Blight, Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln: A Relationship in Language, Politics, and Memory (Milwaukee: Marquette University Press, 2001).

David Blight, Frederick Douglass’ Civil War: Keeping Faith in Jubilee (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1991).

Eric Foner, The Fiery Trial: Abraham Lincoln and American Slavery (New York: Norton, 2011).

Russell Freedman, Abraham Lincoln & Frederick Douglass: The Story Behind an American Friendship (New York: Clarion Books, 2012). For young readers.

Paul Kendrick, Douglass and Lincoln: How a Revolutionary Black Leader and a Reluctant Liberator Struggled to End Slavery and Save the Union (New York: Walker & Company, 2008).

James Oakes, The Radical and the Republican: Frederick Douglass, Abraham Lincoln, and The Triumph of Antislavery Politics (New York: Norton, 2007).

John Stauffer, Giants: The Parallel Lives of Frederick Douglass & Abraham Lincoln (New York: Twelve, 2008).

Katherine Scott Sturdevant and Stephen Collins, “Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln on Black Equity in the Civil War,” Black History Bulletin 73:2 (Summer 2010): 8.

Dwight Jon Zimmerman and Wayne Vansant, The Hammer and the Anvil: Frederick Douglass, Abraham Lincoln, and the End of Slavery in America (New York: Hill and Wang, 2012). Graphic novel aimed at high school students.