The Diary of Ella Jane Osborn, World War I US Army Nurse

by Susan F. Saidenberg

The unpublished diary of Ella Jane Osborn (1881–1966) in the Gilder Lehrman Collection opens an extraordinary window into the daily experiences of one American woman stationed in a US Army hospital in a dangerous and contested battle zone during the final year of World War I. Osborn’s daily entries serve as an uncensored record and provide an interesting counterpoint to the published writings of Ellen La Motte and Mary Borden, two American volunteer nurses whose polished, edited accounts of their activities document the brutal nature of war devoid of nobility or ideals. Osborn’s handwritten diary permits us to peek over her shoulder and be there to observe the life of an American nurse stationed just miles away from the bloody battles of 1918.

The first entry in Osborn’s diary is dated January 18, 1918, and captures her sense of anticipation and her eagerness to participate in active service overseas:

About 4 oclock . . . received word the Unit was to mobilize & report to Ellis Island with out delay, so there was some excitement, most of us had to sit up most the night & pack

When she "consented" to enlist—as the military termed it—Osborn, from Wainscott, Long Island, was thirty-six years old and working as a nurse in a New York City hospital. On February 6 she sailed from New York, landing in Great Britain, and then traveled by boat and train to her post at an evacuation hospital in Toul, a town in northeast France, close to the German border.

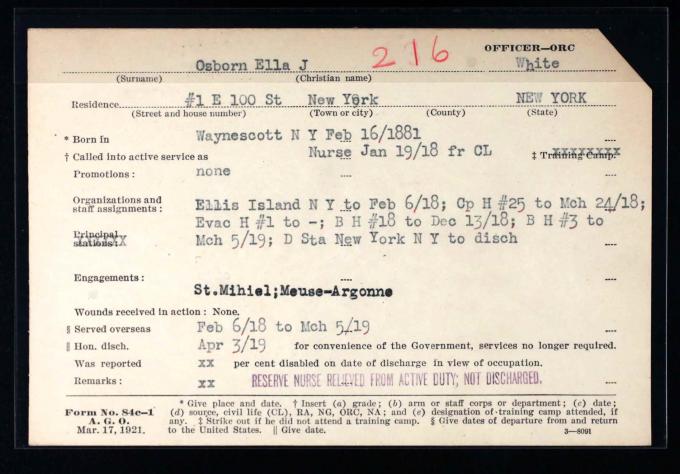

Osborn made daily entries in the diary from the moment she signed up and continued until April 3, 1919, when she was "relieved from active duty; not discharged," according to her military service record:

Osborn’s entries are primarily a record of her tasks as a nurse in a combat-zone hospital, as well as of social activities with a group of friends she made among the nurses. These activities included trips to a nearby town, excursions with servicemen, shopping, picnics, and dinners in hotels. The entries, written in matter-of-fact language, combine descriptions of her work treating horribly wounded soldiers with comments about having tea, meeting with friends, or hitching rides in ambulances. The following entries from July 1918 are typical of Osborn in their straightforward, unembellished style:

July 6 We had a busy day. Was alone a good part of the day as 18 nurses went back to their base and 18 new ones came.

July 7. Sun. Busy all day, came off after supper.

July 8. Miss Rottman, Miss Lent & I went to Bruley, and had an omlet, also bought some French cake which we could not eat.

Mon July 29. Went to the dressing room this morning had 22 dressings. 2 under anesthesia, did not get off for any time & came off dead tired & went to bed

The diary is also a record of the challenging and perilous conditions in which Osborn worked. The evacuation hospital in which she was stationed was on contested land between France and Germany, close to the fierce final battles between the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) and the Germans.

In the two entries below, Osborn describes the German air attacks and bombing raids she witnessed in July 1918, as well as the response from Allied guns:

July 15. About 11 P.M. we heard the Anti-Air-Craft guns and the Search light from St Michael Hill flashed across our window. We got up & had a very interesting time the Shrapnel was flying all around us—and a piece went through the roof of one of the canvas tents where the boys were sleeping but no one was hurt. The Bosh come nearer & nearer all the time.

July 16 - Tues. A Bosh airplane over this morning which we could see distinctly, the Anti-guns shot Several times at it – They usually come over the next morning to see what damage they did the night before.

Surprisingly, Osborn chooses to comment on a humorous sight in the midst of an attack, depicting the chaos among her fellow nurses:

July 18. Thurs. About 11 oclock we were awaken and told to get to the dug out (we never knew there was one before) so up we got, mad because we had to get out, the sirens at Toul started to blow also our own, we went to the dug out but it wasn’t very comfortable & we came back & went to bed. The Bosh came right over us but did not drop a bomb near us. later on they came back & the Anti guns fired at them, they dropped several bombs on Toul—The dug out was a long ways off and the girls were a sight going down, some with their hair flying, some in kimonas & some in bed room Slippers & no stockings

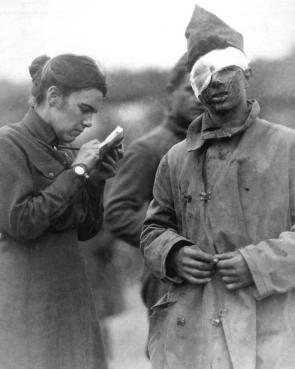

Osborn describes her work in the wards and the care she provides for wounded soldiers in a blunt yet empathetic way:

Osborn describes her work in the wards and the care she provides for wounded soldiers in a blunt yet empathetic way:

Fri. May 31st nearly 400 of our boys were gased last night and are at 102 field Hosp. some are very bad—some say it was Phosgene gas and others say Mustard.

June 17. Total of cases admitted yesterday 148. I went to bed & took a good sleep. The boys were very badly shot up the worst wounded yet. one boy has 16 big wounds. 12 died. six prisoners brought in—one died later

July 18. Thurs. Found three very sick patients on my ward when I went on duty. The three of them were all hurt by the same explosive shell, three others were killed & three others hurt & one killed.

Osborn’s account of the suffering of injured soldiers offers no clues about her emotional state or the impact on her psyche of tending each day to wounded and dying men. Perhaps Osborn’s detachment helped her maintain equilibrium and enabled her to survive the experience of war and cope with the omnipresence of death.

Nurse Osborn refers to her patients as "the boys" and usually does not identify them by name. Yet, in one exceptional instance, she poignantly records the story of 2nd Lt. Lynn Harriman of Warner, New Hampshire, who fought with the 101st Infantry Regiment, 26th Division of the AEF:

May 27. Mon. I am in the officers ward but like taking care of the boys much better. Admitted Lt Lynn Harriman – he was on duty at the front in France on May 27-1918—Enemy put over a barrage followed by an attack – In the Strugglle he was hit by the Enemy's bullet & wounding him in the left shoulder – and passing downward the lung, he lie in the trenches unable to move (paralyzed from waist down) for two hours, while lying there a bunch of germans came along with large clubs & carrying bombs, realizing he could not move he made believe dead.

Osborn notes that despite his wounds, Harriman opened fire on the Germans, "dropping one or two & causing the others to flee." On May 31, she reports that "Lt Harriman died today—just after he died word came from General Pershing that he had been given the D[istinguished] S[ervice] C[ross]."

Although Osborn does not comment on how Harriman’s or other soldiers’ deaths affected her, she made frequent trips to the cemetery with her friend Miss Forsythe to lay flowers on the graves. In the following entry, she chose to record a moving event:

August 11. Chaplain Hyman of the 82 Div & the 326 Regiment came down and asked for three of us girls to go up & help them decorate the graves of the boys from his division, 12 of them buried in one day. He said we were to take the place of their mothers & Sister who could not be there. We placed the wreaths on each of their graves.

Osborn reserves her most enthusiastic and emotional comments for the victories and advances of the American troops. Her decision to enlist was a testament to her patriotism—nurses volunteered to serve and none were ever drafted. She frequently notes that the troops are making great progress, and also eagerly records the news of the impending armistice:

Sept. 13 Fri. News exciting & very good. Allies advancing taking Tours & prisoners, three German Ambulances have been taken & one is being used to transfer our p[a]t[ient]s from the field here. The boys told us they were carried in by the german prisoners, they were made to act as stretcher bearers, . . . Worked 18 hours straight.

For Ella Osborn as for many other American nurses and soldiers who were sent to Europe in 1918, service presented an opportunity to visit monuments, churches, and historical sites in France and England. On October 29, near the end of her official tour of duty, Osborn left Toul and went on a vacation promised to her by the Army in August. She traveled to Paris, Nice, and the south of France. She returned to her station in Toul in November 1918 and suffered a mild case of influenza. On February 17, 1919, Osborn joined a group of nurses on a ship sailing from Bordeaux, arriving in New York City on March 5, 1919. Osborn was relieved of duty on April 3, 1919. The final entry in her journal, dated April 29, 1919, reads "Married."

The diary of Ella Osborn is a fascinating and valuable record, a rare document that enables us to view World War I through the words and eyes of one who experienced it firsthand.

Osborn never wrote about the meaning of the war for her as an American nurse. Yet on July 29–30, 1918, she chose to transcribe in full two major poems about the war: "In Flanders Fields" by Lt. Col. John McCrae and "The Answer" by Lt. J. A. Armstrong. Perhaps these powerful lamentations on death held a special meaning for her and reflected her deeply held but unexpressed response to the horrors of war.

Susan F. Saidenberg is the Director of Publications and Exhibitions at the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History and the senior project editor of the award-winning series People, Places, Politics: History in a Box. Her recent publications include Slavery in the Founding Era: Literary Contexts (Gilder Lehrman Institute, 2005), Freedom to Move: Immigration and Migration in US History (GLI, 2012), and The Twentieth Century: The United States and the World, 1898–1991 (GLI, 2014).