America and the China Trade

by William R. Sargent

On a quarter-mile strip of land in the bustling city of Canton (Guangzhou), China, trade was conducted between merchants from China and the eastern seaboard of America, beginning in 1784 and lasting until the mid-nineteenth century. The starting date for this is precise—February 22, 1784—but there is a longer and far more complicated story.

Trade for the luxury goods that the Chinese (and no one else) could produce had already been taking place along arduous land routes known as the Silk Road for a millennium. These trails ran through Western China to Eastern Europe, as well as to India, Persia, and the Roman Empire. Spices and silk were the major commodities then, with some porcelains and, much later, tea. Discovering a quick, direct, and therefore more lucrative sea route was the goal of many, including Christopher Columbus, who thought he had indeed discovered the Indies when landing in the Americas. It was the Portuguese, however, who would be the first to make the momentous discovery of a viable sea route in the fifteenth century. At the turn of the sixteenth century the Dutch followed in the path of the Portuguese, and quickly on their heels came the English, Spanish, French, and other Europeans. The goods most often sought in those years included spices, silks, porcelains, precious stones, and other luxury commodities.

Spanish merchants brought China trade goods to the shores of North America by way of the Manila Galleon trade as early as 1565; the Dutch trade brought similar goods to New Amsterdam in the seventeenth century. The English arrived on the American continent with Chinese goods acquired through the English East India Company. Seventeenth-century archaeological evidence on the east coast includes wine cups discovered along the James River Basin and bowls found along the Hudson River. Seventeenth-century estate inventories recording Chinese porcelains in Dutch and English households also substantiate the importance of Chinese goods in North America.

During the seventeenth century, the presence and influence of Chinese luxury goods in the American colonies were profound. Among the most enduring reflections of this impact are furniture items made to imitate Asian lacquer ware and Chinese-style engravings on colonial silver—all examples of "chinoiserie," the artistic interpretation in the West of Chinese styles.

Colonial American access to luxury Chinese goods was limited, by the English Navigation Acts of 1651 and subsequent legislation, to merchandise shipped to the colonies on British ships out of British ports. It is a well-known story that the American Revolution was fomented by "taxation without representation" and that the main complaint was taxation on Chinese tea transshipped on British vessels.

Colonial America was allowed to trade directly with China after the signing of the Treaty of Paris in 1783. Only then were Americans free to take advantage of the profitable trade with the Celestial Empire. The first American ship to trade directly with China was the Empress of China, built as a privateer in 1783 and then used as a merchant ship, leaving New York City on February 22, 1784, and returning in 1785. On May 16, 1785, the Pennsylvania Packet carried a report on the successful arrival of the ship: "As the ship has returned with a full cargo, and of such articles as we generally import from Europe, a correspondent observes that it presages a future happy period of our being able to dispense with that burdensome and unnecessary traffick, which heretofore we have carried on with Europe."

America was off and running, establishing itself as an economic world power, taking a lead in an Asian trade that was receding in Europe. Fortunes were made by dozens if not hundreds of entrepreneurial sea captains and merchants. New York, Salem, Boston, and Providence were the major ports engaged in the trade with China, but from Maine and Connecticut to Maryland and Pennsylvania, traders joined the rush to make their fortunes in what could be a very profitable business.

Initially the primary cargoes American traders took to China were silver specie (coins) and ginseng. Both continued to be important for American traders, but efforts were expanded to include seal fur from the Pacific Northwest, sandalwood, and spices, plus bird’s nest and bêche-de-mer from what were then known as the Sandwich Islands. Efforts to secure these goods led to American interest in Alaska and the Hawai’ian Islands.

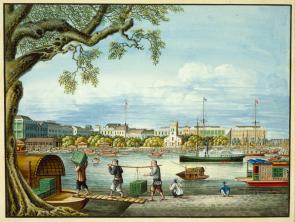

Samuel Shaw, supercargo on the Empress of China, America’s first ship to Canton, wrote: "The Factories at Canton, occupying less than a quarter of a mile in front, are situated on the bank of the river . . . The [lives] of the Europeans are extremely confined; there being, besides the quay, only a few streets in the suburbs, occupied by the trading-people, which they are allowed to frequent. Europeans, after a dozen years’ residence, have not seen more than what the first month presented to view." There were thirteen buildings rented to foreign traders called hongs (from the Cantonese word for company or business, hang). Each was two stories with storerooms on the first floor and accommodations on the second where agents (factors, hence the term "factories") lived during the short trading season. In front of these were poles from which the flags of countries in residence would fly, including America’s.

Each factory was under the watchful eye of a Chinese merchant responsible for making sure Westerners obeyed the laws of China. One of these merchants was Wu Bingjian (1769–1843), known to American merchants as Houqua. He was a favorite of American merchants and the affection was returned. His friendship with Americans led to his investing in American railroads. He amassed a fortune estimated at $26 million, making him one of the richest men in the world at the time.

Tea and silk, the major commodities, were consumed or easily damaged and discarded, but many porcelains have survived to the present day as a permanent reminder of the demand for Chinese goods in America. An advertisement published in the Providence Gazette on May 12, 1804, illustrates the popularity of Chinese porcelains, announcing the availability of specific designs and describing the procurement procedure: "Yam Shinqua, China-Ware Merchant, at Canton, Begs Leave respectfully to inform the American Merchants, Supercargoes, and Captains, that he procures to be Manufactured, in the Best Manner, all sorts of China-Ware with Arms, Cyphers, and other Decorations (if required) painted in a very superior Style, and on the most reasonable Terms. All orders carefully and promptly attended to. Canton, Jan. 8, 1804."

The demand from China for silver as the main trade commodity resulted in a silver shortage in the West, which prompted European and American traders to initiate a trade in opium instead. The Chinese effort to stop this illicit trade resulted in the First Opium War (1839–1842) after China banned the import of British opium. The Chinese loss resulted in the Treaty of Nanking in 1842 between China and Great Britain, which ended the so-called "factory" system and opened additional ports to foreign trade, including Xiamen, Fuzhou, Ningbo, and Shanghai. A second treaty, between China and the United States, the Treaty of Wangxia, was signed in 1844. A Second Opium War, lasting from 1856 to 1860, was fought by China against English and French forces.

While significant trade waned after the mid-nineteenth century (tea, silk, and porcelain were now produced all over the world), it has continued in other ways to the present time. Despite the diminished importance of trade between America and China, the influence of the China trade and its arts on America was and continues to be significant. In 1876 the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia sparked a renewed interest in Chinese decorative arts and commodities, as would many subsequent expositions. In the early twentieth century, sections of large American cities developed enclaves, Chinatowns, which became centers of a new type of outlet for China trade arts: souvenir and curio shops.

In 1941 the Metropolitan Museum of Art held a groundbreaking exhibition of Chinese export art, The China Trade and Its Influences, to celebrate "the manifold aspects of this important cultural exchange." Many books have been published and exhibitions held since then to celebrate the long and significant political, artistic, cultural, and economic relationship America has had with China. Major exhibition catalogs include David Howard’s New York and the China Trade (1984) and Jean Gordon Lee’s Philadelphia and the China Trade (1984). Among the best studies of the past decade are Patrick Conner’s Western Merchants in South China as Depicted in Chinese Art (2009) and Paul A. Van Dyke’s monograph on eighteenth-century trade in Canton and Macao (2011). Many historic houses and museums on the eastern seaboard explore local connections with the China trade. Foremost among these is the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts, which holds the largest collection in the world of Asian export art.

There is a rapidly increasing interest among Chinese collectors in the history of trade with America, and museums are being developed in mainland China exploring the history of trade with the West. There are trade-focused exhibitions at the Guangdong Museum, Guangzhou, and the Nanchang University Museum, Nanchang, as well as continuing displays in the trade galleries of the Hong Kong Museum of Art and the Hong Kong Maritime Museum. A recent exhibition at the Palace Museum in Beijing of export ceramics from the British Museum and the Victoria and Albert Museum was the first in the capital city to expose the public to the trade in ceramics between China and the West. These exhibitions, along with the appearance of chronologies of the China trade on museum and university websites, demonstrate that interest in this crucial aspect of US-China relations is flourishing in the twenty-first century.

William R. Sargent, former curator of Asian export art at the Peabody Essex Museum, is Independent Curator at William R. Sargent Consulting and a guest curator at the Asian Civilisations Museum in Singapore. His publications include Treasures of Chinese Export Ceramics from the Peabody Essex Museum (Yale University Press, 2012).