Photographing the Transcontinental Railroad

by Glenn Willumson

On a brisk May afternoon, in the high desert of Utah, the shrill tap of the telegraph key simultaneously announced the completion of North America’s first transcontinental railroad to cities across the United States. Immediately church bells rang, cannons fired, and spontaneous parades celebrated the great engineering triumph. Today, however, the sound of celebration has long since faded. Our appreciation of the transcontinental railroad is framed today not by sound but by sight. The photographs, not only of the Golden Spike Ceremony at Promontory, Utah, but also of the years of construction, create a vivid picture of this tremendous undertaking and, in the broadest sense, of the industrial progress that characterized the second half of the nineteenth century in the United States. Each of the rival railroad companies employed a special photographer and each of these men brought unique characteristics to the project of framing the railroad for the contemporary public and for future generations.

On a brisk May afternoon, in the high desert of Utah, the shrill tap of the telegraph key simultaneously announced the completion of North America’s first transcontinental railroad to cities across the United States. Immediately church bells rang, cannons fired, and spontaneous parades celebrated the great engineering triumph. Today, however, the sound of celebration has long since faded. Our appreciation of the transcontinental railroad is framed today not by sound but by sight. The photographs, not only of the Golden Spike Ceremony at Promontory, Utah, but also of the years of construction, create a vivid picture of this tremendous undertaking and, in the broadest sense, of the industrial progress that characterized the second half of the nineteenth century in the United States. Each of the rival railroad companies employed a special photographer and each of these men brought unique characteristics to the project of framing the railroad for the contemporary public and for future generations.

Alfred Hart (1816–1908), the photographer of the Central Pacific Railroad, was a former Connecticut portrait and history painter who moved to California in the 1860s. We don’t know why he came west, but in January 1866, at the age of fifty, Hart became the exclusive photographer of the Central Pacific Railroad. He specialized in stereography—a form of photography in which paired photographs that appear to be identical, when placed in a special viewing device, merge to form a single image with three-dimensional depth. The visual results were spectacular, particularly when the stereographs were made by someone of Hart’s skill. He used imaginative compositions, often supported by creative titles, to record the progress of construction from the California state capital in Sacramento eastward over the Sierra Nevada Mountains and through Nevada and Utah.

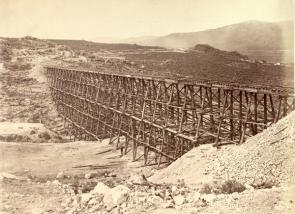

Andrew Russell (1829–1902), the photographer of the Union Pacific Railroad, was a landscape painter in upstate New York before he enlisted in the 141st Regiment of the New York Infantry in 1862. Russell learned photography during the Civil War and worked for General Herman Haupt and the US Military Railroad. It is likely that these military connections helped him secure a commission to photograph the Union Pacific Railroad during the final year of its construction in 1868 and after the completion of the line in 1869. Unlike Hart, Russell did not limit himself to one photographic format; he made both stereographic and large format (10 x 13 inches) negatives. Although Russell worked far from photographic suppliers and lived under harsh environmental conditions, his photographs show a scrupulous attention to visual description and detail.

It took stamina and ingenuity to make any photographs in the West in the 1860s; the issues associated with the railroad construction only compounded the challenge. Both Hart and Russell had to carry not only their cameras and lenses but also glass and chemicals. Unlike digital photographers today, nineteenth-century photographers created a negative for each picture, which was later printed to make the positive image that we consider the photograph. But this is the end of a long process requiring manual dexterity and physical fortitude. A viscous solution of photographic chemicals had to be carefully poured onto a prepared glass plate negative, tilted so that it coated evenly, and then, still wet, carried to the camera and exposed. When sufficient time had elapsed, from a few seconds to almost a minute, the photographer removed the fragile glass plate from the back of the camera, carried it back to the darkroom, and developed it before the light-sensitive solution dried. For all this to happen in a short space of time, photographers needed to transport camera, tripod, lenses, glass, chemicals, and trays to each photographic location. Alfred Hart, traveling back and forth from Sacramento, had a full-sized photographic wagon outfitted with a complete darkroom; Andrew Russell, in the field for months at a time, had to make do with a tall rectangular box that he mounted on the back of a buckboard wagon.

It is easy to understand the popularity of these historic photographs. They seem to offer a window into a triumphal moment in the history of the United States. What we must recognize, however, is that this sense of transparency is an illusion. These images are, in fact, complex representations whose meaning goes far beyond simple documentation or even the intentions of any single person. The photographs that we too often assume are straightforward and uncomplicated are influenced by the photographers; the men to whom they hoped to sell the photographs, Central Pacific attorney E. B. Crocker and Union Pacific vice president Thomas Durant; and a public the directors hoped to influence. The way these images look, the meanings they convey, and the power they exert to this very day are a result of the triangulation of intentions among maker, client, and audience.

It is easy to understand the popularity of these historic photographs. They seem to offer a window into a triumphal moment in the history of the United States. What we must recognize, however, is that this sense of transparency is an illusion. These images are, in fact, complex representations whose meaning goes far beyond simple documentation or even the intentions of any single person. The photographs that we too often assume are straightforward and uncomplicated are influenced by the photographers; the men to whom they hoped to sell the photographs, Central Pacific attorney E. B. Crocker and Union Pacific vice president Thomas Durant; and a public the directors hoped to influence. The way these images look, the meanings they convey, and the power they exert to this very day are a result of the triangulation of intentions among maker, client, and audience.

For their part, E. B. Crocker and Thomas Durant each had significantly different understandings of the value of photography. Because there was tremendous skepticism about the ability of the Central Pacific to construct a railroad over the treacherous terrain of the Sierra Nevada Mountains, Crocker needed proof of the company’s success. To this end, beginning in January 1866, he created a corporate photo archive, purchasing negatives directly from Alfred Hart and titling and sequencing 364 negatives into stories of railroad progress. For his part, Hart created visually dramatic pictures venturing far from his wagon, climbing up the side of a mountain or on top of a locomotive.

Once the photographs entered the Central Pacific archive, they were printed and distributed widely. Many were sent to New York where the company’s vice president, Collis Huntington, distributed them to government officials, potential investors, and industrial suppliers. Crocker understood that stereographic originals could influence individuals, but reproductions could influence thousands of people. Consequently, he also had them reproduced as wood engravings in illustrated newspapers such as Harper’s Weekly and the Illustrated London News.

Unlike Crocker, Thomas Durant did not purchase negatives and, consequently, Andrew Russell was largely on his own during his long stays in the West. One of the most remarkable aspects of Russell’s photographs of the Union Pacific is his skill with the camera. Because negatives were not enlarged in the 1860s, the size of the finished photograph was the same as the negative, and the larger the negative, the more difficult to get the light-sensitive chemicals onto the glass plate. Russell’s 10 x 13-inch negatives were among the largest and show great clarity and detail. Durant used the impressive size of Russell’s photographs to great advantage.

Durant wanted to monetize the abundant land from government grants by encouraging investment and emigration. Consequently, a month before the Promontory celebration, Andrew Russell, with the backing of the Union Pacific, produced The Great West Illustrated, a lavish album of fifty large-format photographs representing the West from Cheyenne to Salt Lake City. Highlighting the natural resources of the newly opened lands west of the Missouri River, Russell’s photographs offered impressive visual proof of the infrastructure that the railroad had fostered—hotels, windmills, cities—and of the raw materials—timber and water—that were available to settlers and investors alike.

The railroad, and its concomitant picture production, played a vital role in the post–Civil War history of the United States. For an earlier generation, the Mason-Dixon Line, congressional representation, and slavery were issues played out against a backdrop of north and south. The prospect of a transcontinental railroad allowed the federalized union to turn its martial energies, so destructive during the military campaigns of the Civil War, to a new project that re-created the United States as an east-west nation. The spectacular success of the railroad builders, however, would have remained only a technical and practical accomplishment were it not for the accompanying picture production. The photographs that surrounded the railroads’ efforts were the vehicles for the ideological reconstruction of America as both an industrial nation and a country with a grand new western horizon.

Glenn Willumson is Florida Foundation Research Professor of Art History and the director of the graduate program in museology at the University of Florida. He is the author of Iron Muse: Photographing the Transcontinental Railroad (2013).