America the Newcomer: Claiming the Louisiana Purchase

by Elliott West

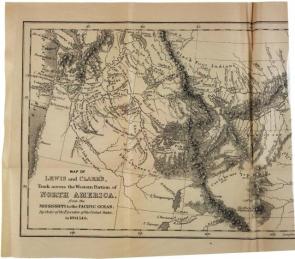

The Lewis and Clark expedition is rightly considered one of the great American stories. In May of 1804 Meriwether Lewis and William Clark set off by keelboat up the Missouri River with thirty-one men, the "Corps of Discovery," on an expedition authorized by Congress at the request of Thomas Jefferson. President Jefferson had instructed the two men, commissioned army captains, to ascend the Missouri to its source, then find the most accessible route across the Rocky Mountains to the Pacific Ocean. They were also to open peaceful relations with Native peoples, explore the possibilities of trade, and gather scientific information and examples of western flora and fauna. After a near-violent brush with the Teton Sioux (Lakota) and the expedition’s only death, probably from appendicitis, the Corps spent a frigid winter in a log fort they built at the villages of the Mandan and Hidatsa, near present-day Bismarck, North Dakota. During their stay they hired a trapper, Toussaint Charbonneau, and his Shoshoni wife, Sacagawea, as interpreters and guides. In April 1805 they resumed their ascent of the Missouri.

The Lewis and Clark expedition is rightly considered one of the great American stories. In May of 1804 Meriwether Lewis and William Clark set off by keelboat up the Missouri River with thirty-one men, the "Corps of Discovery," on an expedition authorized by Congress at the request of Thomas Jefferson. President Jefferson had instructed the two men, commissioned army captains, to ascend the Missouri to its source, then find the most accessible route across the Rocky Mountains to the Pacific Ocean. They were also to open peaceful relations with Native peoples, explore the possibilities of trade, and gather scientific information and examples of western flora and fauna. After a near-violent brush with the Teton Sioux (Lakota) and the expedition’s only death, probably from appendicitis, the Corps spent a frigid winter in a log fort they built at the villages of the Mandan and Hidatsa, near present-day Bismarck, North Dakota. During their stay they hired a trapper, Toussaint Charbonneau, and his Shoshoni wife, Sacagawea, as interpreters and guides. In April 1805 they resumed their ascent of the Missouri.

Now they were in country previously unknown to white outsiders. Paddling canoes and dodging grizzly bears (the first seen by white Americans), the Corps made their way to the Missouri headwaters in the northern Rockies. The first American Indians they met were Shoshonis led, astonishingly, by Sacagawea’s brother, Cameahwait, whom she had not seen since the Blackfeet had captured her as a young girl. Lewis and Clark acquired horses from them, as well as the advice they used to cross the mountains that proved a far more difficult barrier than they had expected. After descending the Columbia River, they spent a miserable second winter near its mouth, then retraced their outward journey. Lewis and three others had a brief fight with the Blackfeet that left two warriors dead during a detour up the Marias River, a northern tributary of the Missouri. It was the expedition’s only violent clash with American Indians. The rest of the journey was uneventful, and in September 1806, the Corps reached St. Louis, twenty-seven months after leaving it.

The expedition’s grip on the popular imagination is understandable. It features adventures and trials, close calls and improbable coincidences, exotic encounters and fascinating personalities. To tell its tale we have the superb journals of Lewis and Clark and a few of their fellow travelers. The very power of the story, however, is a shortcoming. Its high drama tempts us to see it as a mythic confrontation with a wilderness untrodden and untouched by a world outside, a land where history had not truly begun. That appeal is especially strong among Americans drawn to an episode that seems to give them a special claim to the land traversed by the captains, and beyond it to the West at large.

In fact, far from setting history in motion, Lewis and Clark were stepping into the middle of developments that had been gathering strength for generations, and as they did they introduced new influences, those of the young nation that a few generations later would dominate the land to the Pacific. When seen in context, the story of the Corps of Discovery becomes a revelation of the West at a moment of accelerating change.

As they moved up the Missouri, for instance, Lewis and Clark were tapping into an ancient and recently invigorated system of trade. The Mandan villages where they spent their first winter were a major transition point of commerce up and down the Missouri and overland to Canada and the southern plains. For a quarter century before the expedition, French and British traders had brought in goods ranging from firearms and copper bells to peppermint candy and corduroy trousers. Some of the horses the Corps acquired in the Rockies had been branded as colts in Spanish New Mexico. As they proceeded the captains found evidence of foreign presence—trade goods among peoples of the Columbia basin and, during their winter on the Pacific coast, a young woman with a British trader’s name, "J. Bowmon," tattooed on her arm. As new players in an old trade, the Americans complicated an already complex arrangement. They were welcomed by groups like the Mandan, Shoshoni, and Nez Perce who were eager for fresh sources of goods, especially firearms. Groups that dominated the current system, on the other hand, were in no mood for competition. It was probably no coincidence that the captains’ most hostile reception was from the Teton Sioux, who controlled the cross-plains trade routes, and the Blackfeet, Britain’s prime partners.

The Blackfeet’s European connections are a reminder that the United States was only one of several outside powers looking covetously at the West. Jefferson knew well, in fact, that he was entering quite late into an imperial contest for the region. The immediate goad for organizing the expedition was a book by the British explorer Alexander Mackenzie, whose journey across Canada was the first continental crossing by a non-Indian. When Mackenzie recommended that England plant settlements in the Pacific Northwest, where Russians also had already had a vigorous trading presence, Jefferson decided he had to act. Closer to home, Spain and France had long vied for the allegiance of peoples on the Great Plains. An Indian delegation from Kansas and Missouri had once visited the French court, performing dances at the Paris opera and demonstrating riding skills in the royal woods. This was in 1724, eighty years before Lewis and Clark.

In 1763 France had ceded greater Louisiana, essentially the western watershed of the Mississippi River, to Spain, but in 1800 Napoleon got it back in an effort to re-establish a North American French empire. A looming war with England and a disastrous campaign to subdue the Caribbean island of Saint Domingue led Napoleon to make the stunning offer to sell Louisiana to the United States in 1803. Mere weeks before the Corps’ departure, the Louisiana Purchase was finalized. It doubled the size of the United States and projected it toward the Pacific. When Lewis and Clark began organizing their journey, they assumed they would be launching into foreign territory. Now they would be exploring a western portion of their own nation—country as unknown to its supposed owners as the far side of the moon.

The Louisiana Purchase instantly intensified America’s rivalry with one European power in particular—Spain. Jefferson thought the Missouri would open onto easy access to Spanish settlements in New Mexico (he was wrong). Spanish leaders feared that American settlers would wash across the Mississippi and threaten those settlements (they were right). The Spanish naturally saw the expedition as a challenge to their northern frontier. New Mexican authorities sent no fewer than four military units on failed efforts to arrest Lewis and Clark. Jefferson meanwhile sent two expeditions up the Red River, into what is today Louisiana, Arkansas, and Texas, to reconnoiter the border of New Spain. A third expedition under Lt. Zebulon Pike, dispatched by General James Wilkinson, ascended the Arkansas River, crossed the Rocky Mountains, and was seized in Spanish territory and taken to Mexico before being released. The United States was in a tense standoff with Spanish troops along the Louisiana-Texas border as Lewis and Clark arrived home in St. Louis—dramatic evidence that the captains had toured not a static wilderness but a land in flux.

Those changes only quickened in the years ahead. Lewis and Clark’s reports from the West quickly drew interest from what was arguably the biggest business in the Atlantic World—the fur trade. The demand for beaver hats in Europe and America had depleted the animal population in the eastern woodlands, and descriptions of country teeming with beavers sent freelance trappers into the West almost immediately. In 1810–1811 John Jacob Astor, head of the American Fur Company and America’s first millionaire, hatched an audacious scheme to use a post near the mouth of the Columbia River as the pivot of a trading system sending western beaver pelts in exchange for Asian spices and silks. After the War of 1812 thwarted that ambition, Great Britain’s North West and Hudson’s Bay Companies organized trapping brigades that dominated the Pacific Northwest until the 1820s, when other American businessmen, led by William Ashley and Andrew Henry of St. Louis, again entered the competition.

American "mountain men" fanned out across the West, trapping and searching for untapped beaver populations and gathering at annual rendezvous in the Rocky Mountains to exchange the year’s results for goods brought by wagon from St. Louis. Ranging widely across the region made them profit-driven explorers. Far more than Lewis and Clark and other government expeditions, mountain men filled in what had been empty spaces on the map of the far West.

Like Lewis and Clark, mountain men are often portrayed as mythic figures, in their case as men turning their backs on their society in pursuit of life in the wild. Wild some of them could be. In their buckskins and long hair most were certainly wild-looking. As workers in a global enterprise, however, they were harbingers of economic change, and they were some of the most effective agents in opening the region to the nation that had birthed them.

The changes at work in 1804, as the Corps of Discovery poled its way up the Missouri, still rippled through the region, but the youthful American republic was as a result in a far stronger position in its competition with its European rivals. Control of the West, however, remained with those whose land it had been for millennia.

Elliott West is Alumni Distinguished Professor of History at the University of Arkansas. He is author of, among other books, The Contested Plains: Indians, Goldseekers, and the Rush to Colorado (1998); The Way to the West: Essays on the Central Plains (1995); and, most recently, The Last Indian War: The Nez Perce Story (2009).