The Ideas behind the Declaration

The Second Continental Congress declared that all human beings shared natural rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. Legitimate governments were founded through consent of the governed, and a people retained the right to resist tyrannical governments that threatened natural rights. The Declaration helped justify separation from Britain and the establishment of a new government. Its concepts were drawn from the pages of philosophical, political, and legal books and shaped by conditions in the colonies. No concept, however, was more potentially transformative, or more consequential to later generations, than the idea that “all men are created equal.”

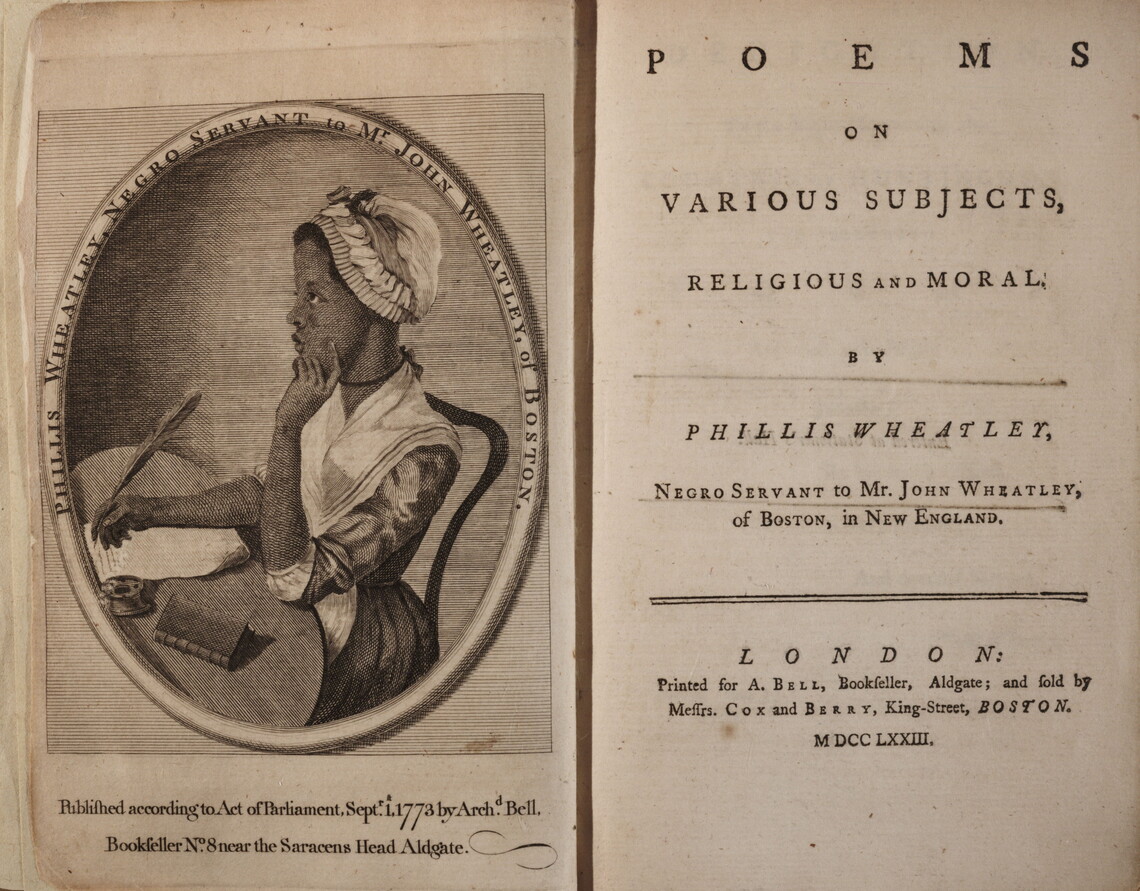

Born in West Africa around 1753, enslaved, and sold at the age of seven to a White family in Boston, Phillis Wheatley would become a literary prodigy and a staunch supporter of the American revolutionary cause. Her landmark 1773 book of poetry helped confirm for readers in Europe and America the idea that neither race nor gender limited a person’s capacity for achievement.

In every human Breast, God has implanted a Principle, which we call Love of Freedom; it is impatient of Oppression, and pants for Deliverance.

—Phillis Wheatley to the Reverend Samson Occom, printed in the Connecticut Gazette, March 11, 1774

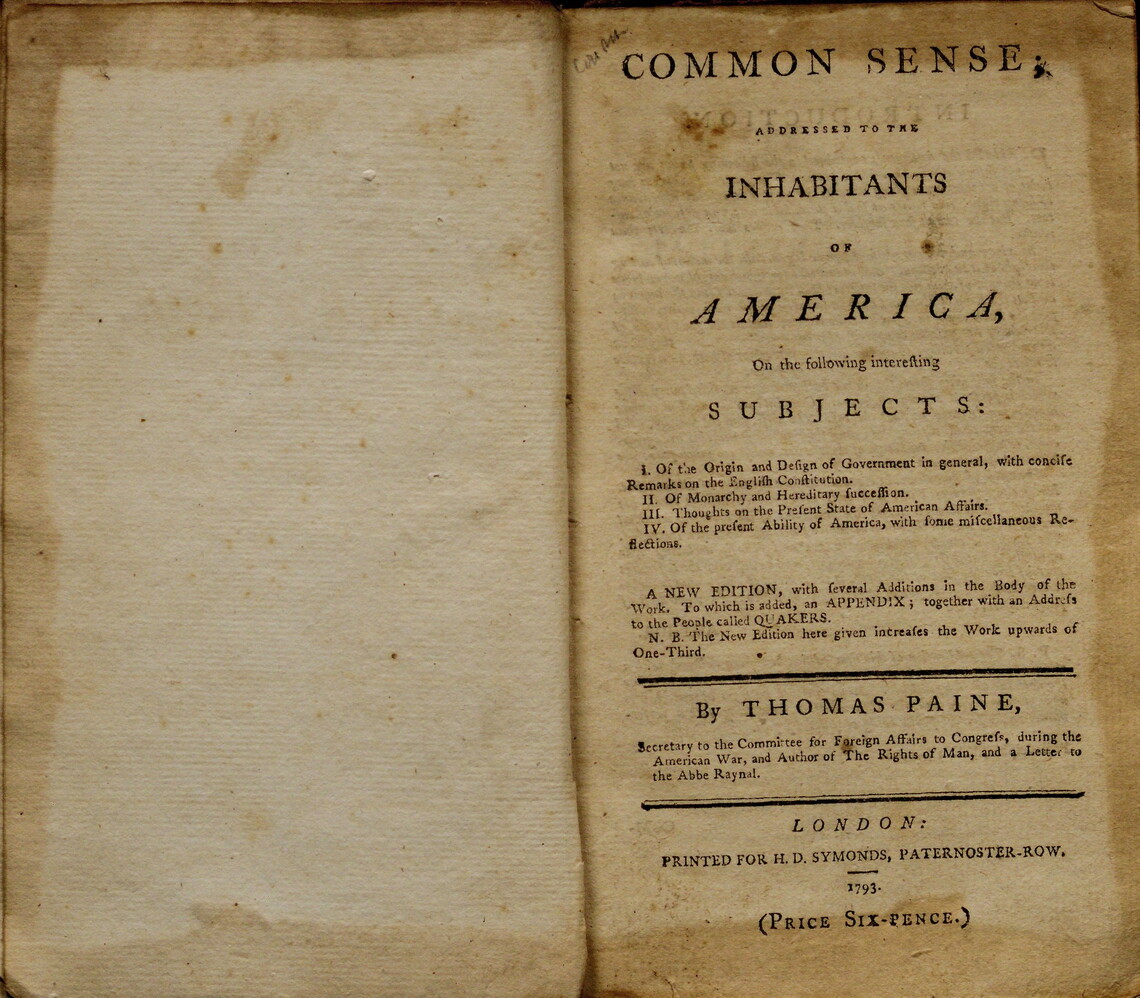

Thomas Paine’s pamphlet proposing separation from Britain was published in Philadelphia in January 1776. Paine shocked readers by calling King George a “Tyrant,” a word printers would not use when the pamphlet reached England. Paine believed that human beings were “originally equals,” that monarchies created inequality, and that “in America the law is King.”

In America the law is king. For as in absolute governments the King is law, so in free countries the law ought to be king; and there ought to be no other.

—Thomas Paine, Common Sense, 1776

Display Full Image

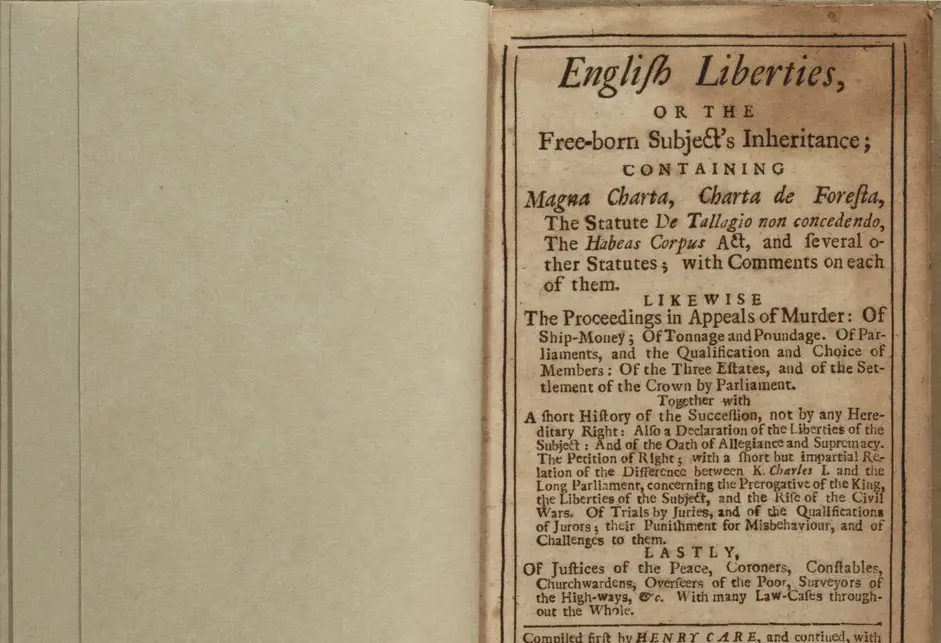

As a teenage apprentice Benjamin Franklin helped print a book about rights, including those delineated by the Magna Carta of 1215. The book celebrated England as a place where “each Man” was born with a “Freedom of his Person, and Property” which he “cannot be deprived of but by his consent.” Influenced by such enlightened ideas, American colonists would claim rights from law and nature.

Benjamin Franklin’s brother James printed this copy of English Liberties, or The Free-born Subject’s Inheritance; Containing Magna Charta, Charta de Foresta, The Statute De Tallagio non concedendo, The Habeas Corpus Act, and several other Statutes, with Comments on each of them, Boston, 1721. (The Gilder Lehrman Institute, GLC01710)

Display Full Image

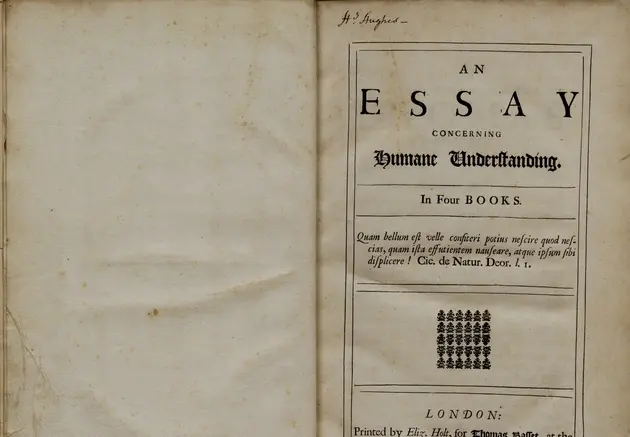

English philosopher John Locke (1632–1704) believed in the natural and original equality of all human beings. While his political thought was influential, his most important book—An Essay Concerning Human[e] Understanding—explored how the mind works. For Locke, education was the chief source of the differences and inequalities between individuals.

John Locke, An Essay Concerning Humane Understanding, London, 1690. (The Gilder Lehrman Institute, GLC00320)

Display Full Image

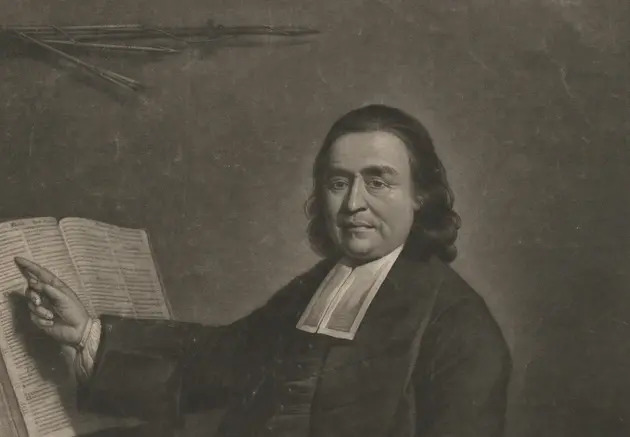

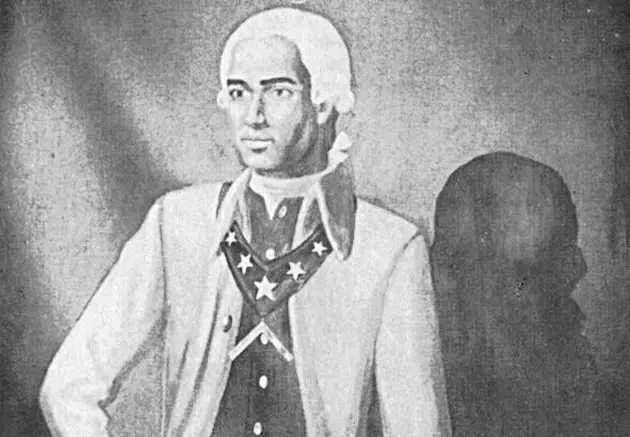

Newly free and one of the most famous writers in the colonies, Phillis Wheatley addressed a letter in 1774 to Samson Occom, a minister and member of the Mohegan nation in Connecticut who had himself achieved great celebrity as a preacher and fundraiser in Britain. In this letter, Wheatley defended the “natural Rights” of enslaved people and openly questioned the morality of colonists who cried for their own liberty while enslaving others.

Samson Occom, mezzotint by Jonathan Spilsbury after Mason Chamberlin, 1768. (National Portrait Gallery)

Display Full Image

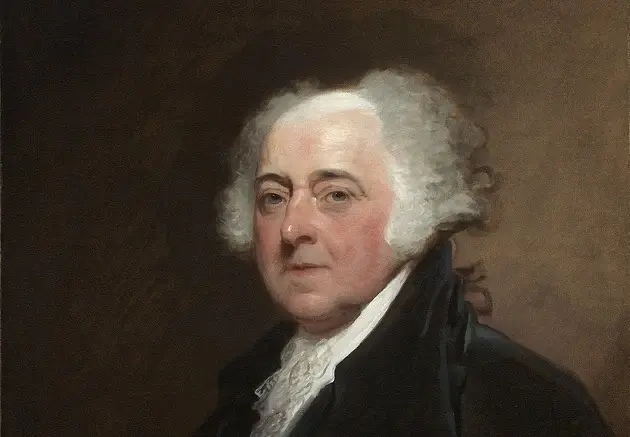

Writing in late 1775 John Adams drew inspiration from Montesquieu (1689–1755), an influential French political philosopher, to develop a “Sketch” for a government based in “Nature and Experience.” To counter “the Effort in human nature towards Tyranny,” the three powers in government—legislative, executive, and judicial—needed to be balanced and equalized.

John Adams, portrait by Gilbert Stuart, 1800/1815. (National Gallery of Art)

Display Full Image

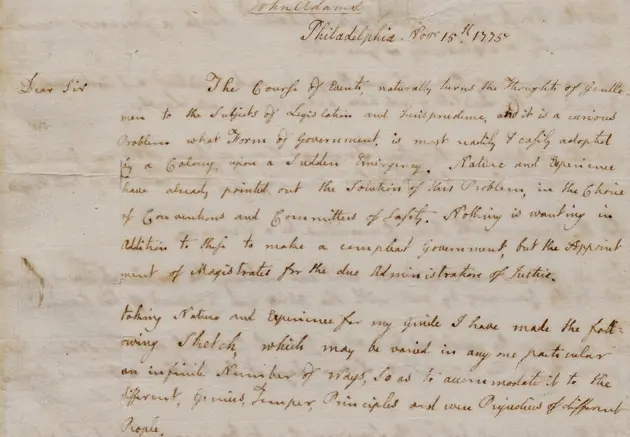

Richard Henry Lee, the Virginia delegate to the Continental Congress who would formally propose declaring independence, visited John Adams on November 14, 1775. The two delegates discussed the forms of government that might be adopted in the colonies in the wake of independence. The next day, Adams drafted this letter outlining the three branches of American government.

John Adams to Richard Henry Lee, November 15, 1775. (The Gilder Lehrman Institute, GLC03864)

The American Revolution

In 1763, few people in Britain or America anticipated American independence. With Britain’s victory over France in the Seven Years’ War, White colonists considered themselves among the freest people in the world. However, the British government soon tightened commercial regulations, limited western land settlement, and imposed new taxes. Colonists claimed these new rules denied their right to equal treatment as subjects in the British Empire. What began as a political protest against Britain ultimately became a revolution that transformed society. Poor White men, women, African Americans, and Native Americans all sought to pursue equality on their own terms.

Display Full Image

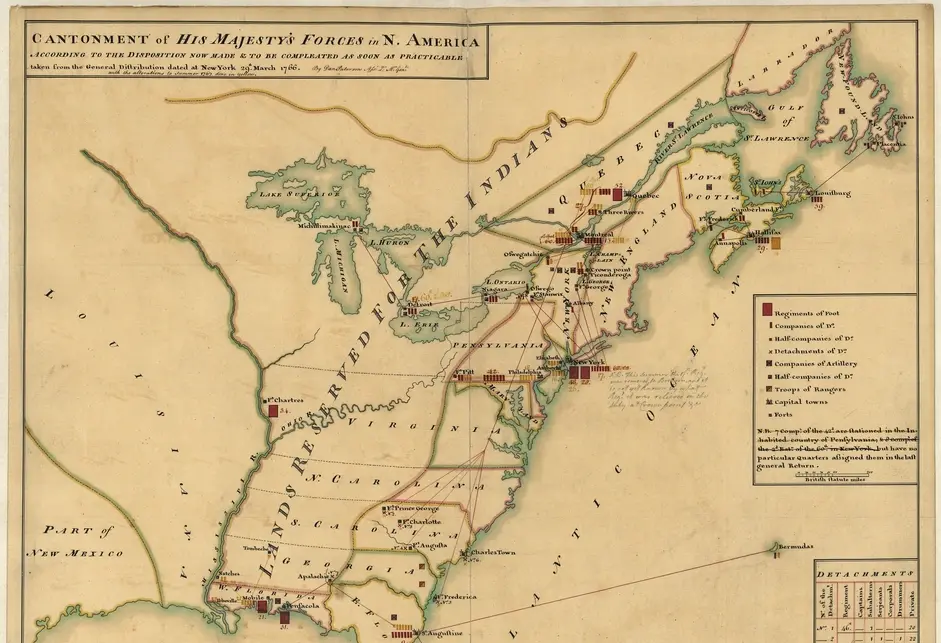

After the Seven Years’ War, the British left forces in America to keep the peace between the colonial settlers and Native Americans.

Cantonment of His Majesty’s Forces in N. America, map by Daniel Paterson, New York, March 29, 1766. (Library of Congress, gm72002042)

Display Full Image

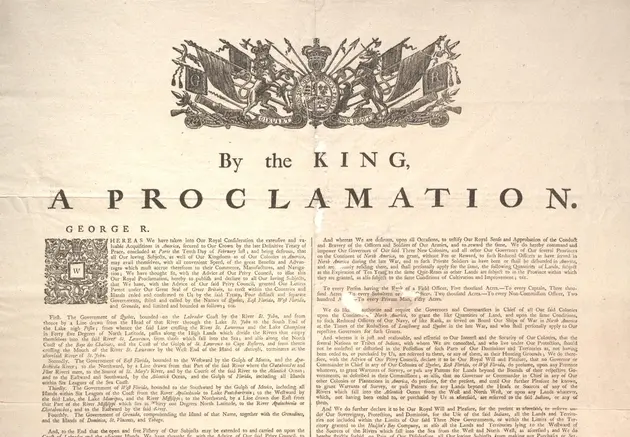

Starting with the Proclamation of 1763, Britain attempted to consolidate its empire. The Proclamation, which prohibited settlement of lands west of the Appalachian Mountains, sought to limit future conflicts with Native Americans. Ultimately, the policy failed to protect Native lands while infuriating colonial American elites with settlement ambitions.

The Proclamation of 1763 initiated a series of imperial reforms in the wake of Britain’s victory over the French in the Seven Years’ War that ultimately ignited the American Revolution. (The Gilder Lehrman Institute, GLC05214)

Display Full Image

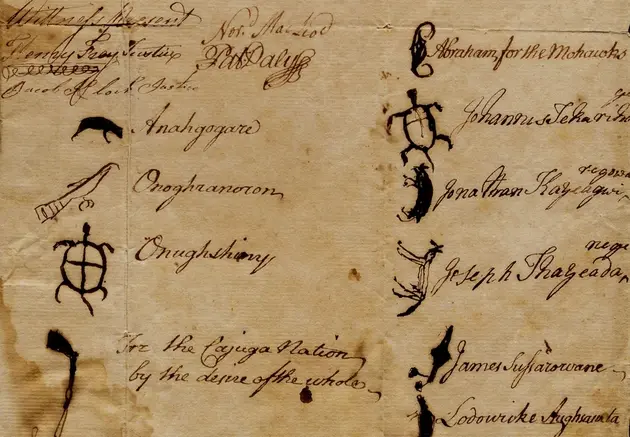

In 1768, the British and leaders of the Haudenosaunee (Six Nations of the Iroquois Confederacy) negotiated a settlement that revised the boundary in the Proclamation of 1763, reflecting ongoing Native sovereignty during the imperial crisis.

Receipt for land negotiated with the Haudenosaunee in the Treaty of Fort Stanwix, signed with the totems of fourteen chiefs, 1768 (The Gilder Lehrman Institute, GLC02548)

Display Full Image

British taxes and regulations inspired broad protests in the American colonies. Initially, the colonists complained of “taxation without representation” since no one residing in the colonies sat in the British Parliament. Over time, the imperial debate grew to concern larger issues of sovereignty, or control, over American affairs.

Paul Revere’s depiction of the Boston Massacre was influential propaganda for the revolution. It also captures the diversity of American protesters. In the lower left corner of this hand-colored copy, Crispus Attucks, a man of African and Native American descent, is correctly depicted as a person of color. The Bloody Massacre Perpetrated in King-Street, engraving by Paul Revere, Boston, 1770. (The Gilder Lehrman Institute, GLC01868)

Display Full Image

American protests split colonial society into rival patriot (emerging American) and loyalist (pro-British) sides. Both groups valued political liberty, but they differed on how to achieve it. Loyalists favored a traditional hierarchical society that emphasized order while patriots increasingly embraced political equality, especially among White men.

This British print depicts rowdy Bostonians forcibly pouring a pot of tea into the mouth of a tarred and feathered tea excise (tax) collector. The Boston Tea Party is in the background. The Bostonian’s Paying the Excise-Man, or Tarring & Feathering, engraving by Philip Dawe, London, October 31, 1774. (The Gilder Lehrman Institute, GLC04961.01)

Display Full Image

Women played a critical role in resisting British policies. They joined crowd actions, penned protests, and supported non-importation (or boycott) efforts against tea and other British goods. The burden of non-importation often fell most heavily on women, who had to produce homespun and other goods in place of British imports.

This deliberately unflattering British depiction of women leaders of non-importation in Edenton, North Carolina, reflects the success of American women in advancing the patriot cause. A Society of Patriotic Ladies, at Edenton in North Carolina, engraving by Philip Dawe, pub. London: Robert Sayer and John Bennett, 1775. (Library of Congress, PC 1 - 5284B)

The American Revolutionary War started with the Battles of Lexington and Concord on April 19, 1775, and spread across North America more than a year before American independence.

The public papers as well as private accounts have Witnessed to the Bravery of the Peasants of Lexington, & the spirit of freedom Breath’d from the Inhabitants of the surrounding Villages.

—Mercy Otis Warren to Catharine Macaulay, August 24, 1775

Display Full Image

The war exposed inequities and differing loyalties in American society. The majority of both African Americans and Native Americans sided with the British, who offered potential freedom for enslaved people and greater respect for Native sovereignty and territory.

The Battle of Lexington April 1775, print by Amos Doolittle, 1775. (Library of Congress)

Display Full Image

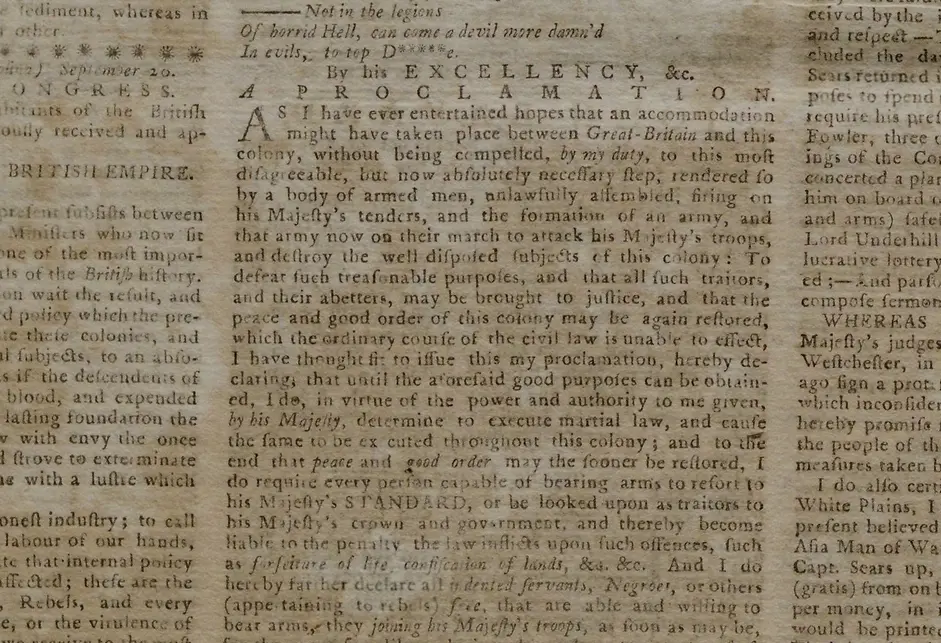

In November 1775, Virginia’s royal governor, Lord Dunmore, offered freedom to enslaved African Americans upon condition that they took up arms for the British. Thousands used Dunmore’s Proclamation and similar British measures to secure their freedom during the Revolutionary War.

Reprinting of Dunmore’s Proclamation of November 7, 1775 in the Pennsylvania Journal and Weekly Advertiser, December 6, 1775. (The Gilder Lehrman Institute, GLC01706)

Declaring Independence

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.

The Second Continental Congress deliberated Thomas Jefferson’s draft of the Declaration of Independence for nearly three full days. Though members of Congress objected to several passages—removing some and rewriting others—they kept the words, “all men are created equal.” The idea of equality was central to the Enlightenment philosophy of natural rights, but after it appeared in the Declaration, it acquired new political significance. Throughout the new nation and beyond, people from all walks of life immediately began to demand equality, and have continued to do so for generations.

In March 1776, Abigail Adams wrote to her husband John, the Continental Congressman. Abigail urged John, as he contemplated laws for the new nation, to “Remember the Ladies” and not give husbands “unlimited power” over their wives. John made light of Abigail’s plea, quipping that the Revolution had “loosened the bands of Government every where.”

[I]n the new Code of Laws which I suppose it will be necessary for you to make I desire you would Remember the Ladies . . . Do not put such unlimited power into the hands of the Husbands.

—Abigail Adams to John Adams, March 31, 1776

To refute the Declaration of Independence, the British ministry hired a lawyer and penman named John Lind. Lind drafted a lengthy pamphlet defending King George III. In the final pages, Lind—collaborating with philosopher Jeremy Bentham—disputed the theory of natural rights and ridiculed Jefferson’s assertion that “all men are created equal.” They made a provocative question explicit: Equal in what way?

"All men," they tell us, "are created equal." This surely is a new discovery; now, for the first time, we learn, that a child, at the moment of his birth, has the same quantity of natural power as the parent, the same quantity of political power as the magistrate.

Display Full Image

Shortly before Thomas Jefferson began to write the Declaration of Independence, the Pennsylvania Evening Post published a draft of the Virginia Declaration of Rights. Authored by George Mason, the draft affirmed, “[A]ll men are born equally free and independent.” This passage inspired Jefferson, but in Virginia, it sparked fears of “civil convulsion.”

George Mason (1725–1792), painting by Louis Mathieu Didier Guillaume after a now-lost portrait by John Hesselius, n.d. (Virginia Museum of History and Culture)

Display Full Image

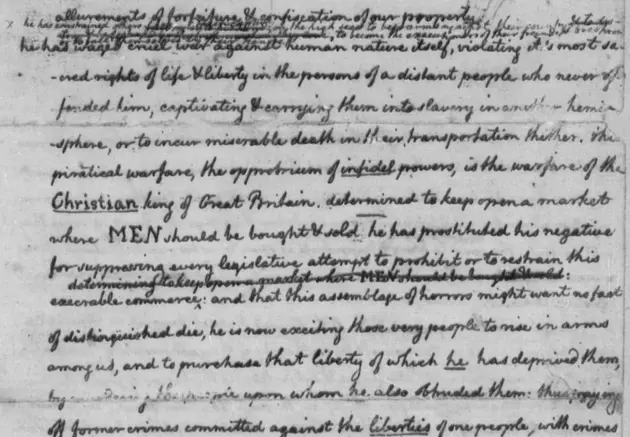

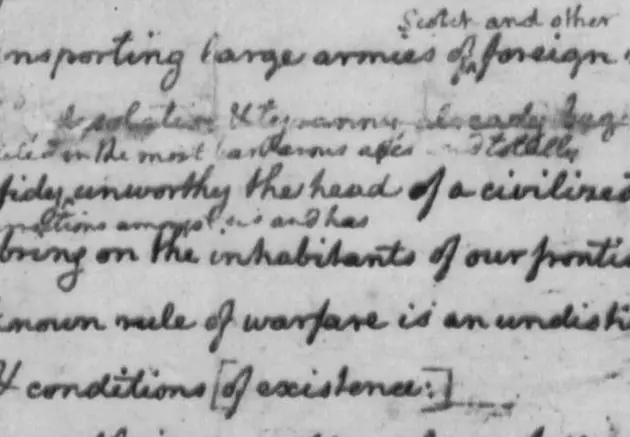

In his rough draft of the Declaration, Thomas Jefferson affirmed that African peoples possess “sacred rights of life & liberty,” and he rebuked King George III for protecting the transatlantic slave trade. Jefferson wrote this despite being a slaveholder himself. Some congressmen, whose constituents invested heavily in slavery, opposed this passage and demanded its removal from the Declaration.

Thomas Jefferson’s Rough Draft of the Declaration of Independence, June 1776. (Library of Congress)

Display Full Image

In the final grievance of the Declaration, Thomas Jefferson blamed King George III for encouraging England’s Native American allies to make war against the former colonies. Jefferson used inflammatory language that he knew would stoke long-standing popular resentment toward Indigenous peoples. He characterized them as “merciless Indian savages.”

Thomas Jefferson’s Rough Draft of the Declaration of Independence, June 1776. (Library of Congress)

Display Full Image

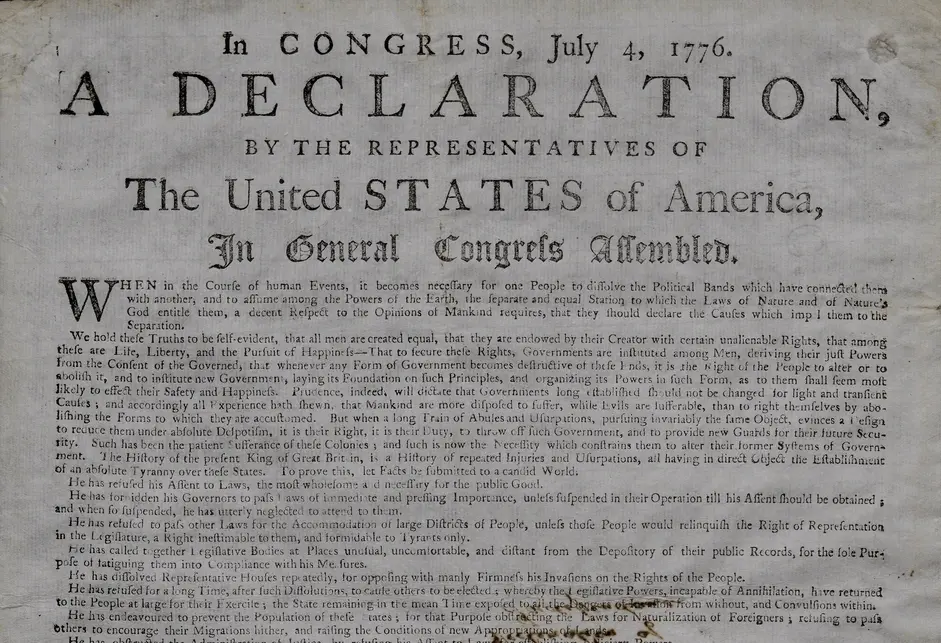

By the end of the summer, no fewer than thirty American newspapers had published the Declaration of Independence. In early August, Peter Timothy, the publisher of the South Carolina Gazette, printed this copy of the Declaration as a broadside, or poster, to be hung in public places around Charleston.

Peter Timothy printed this copy of the Declaration of Independence in August 1776 in Charleston, South Carolina. Timothy would be arrested for treason by British officers in 1780. (The Gilder Lehrman Institute, GLC00959)

Display Full Image

The Second Continental Congress met in the Pennsylvania State House. After Congress adopted the Declaration of Independence, a militia officer read the document to a crowd gathered on the State House lawn. President John Hancock distributed copies to state officials, with instructions that it be published far and wide. In the Continental Army, officers read the Declaration to their soldiers. In Massachusetts, ministers read it from their pulpits. In Virginia, sheriffs read it at local courthouses.

“The Manner in which the American Colonies Declared Themselves Independent of the King of England, throughout the Different Provinces, on July 4, 1776,” engraved illustration in Edward Barnard,The New, Comprehensive and Complete History of England, London, 1782. (Library of Congress)

Display Full Image

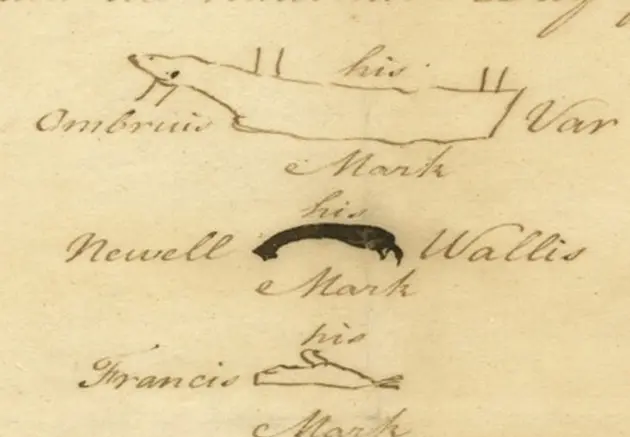

Despite the Declaration’s inflammatory language, General George Washington and the Continental Congress pursued diplomacy with Indigenous nations, encouraging the Maliseet and Mi’kmaq peoples, among many others, to remain neutral or fight in the war against Britain. In mid-July 1776, Massachusetts council president James Bowdoin presented the Declaration of Independence to several Maliseet and Mi’kmaq sachems, who had journeyed to Watertown from their villages in present-day New Brunswick to negotiate a treaty. After an interpreter “fully explained” the document, Maliseet sachem Ambrose St. Aubin replied, “We like it well.”

Ambrose St. Aubin signed the Treaty of Watertown (1776) by drawing his totem, a bear. The transcriber recorded his name as “Ambruis Var.” (University of New Brunswick)

Limits of Independence

A great number of Negroes who are detained in a state of Slavery . . . apprehend that they have, in common with all other Men, a natural and unalienable right to that freedom, which the great Parent of the Universe hath bestowed equally on all Mankind.

—Lancaster Hill, Peter Bess, Brister Slenser, Prince Hall, et al., “The Petition of a Great Number of Negroes Who Are Detained in a State of Slavery,” January 13, 1777.

The Declaration of Independence was a radical document that promised freedom and equality for all. But as the American Revolution unfolded, a glaring gap emerged between promises and reality. Freedom, equal rights, and full citizenship were reserved primarily for White men who owned property. Meanwhile, poor people, women, Black people, and Indigenous peoples remained largely excluded. Property ownership mattered. Some free African American men with property and Indigenous people were permitted to vote, especially those living in urban areas. Women in New Jersey could vote from 1776 through 1807. Within a generation, poor White men demanded—and began to receive—unrestricted voting rights. But women, Black people, and Indigenous peoples were often denied freedom, justice, and equality. In response, they harnessed the Declaration’s language and spirit to fight for freedom and equal rights.

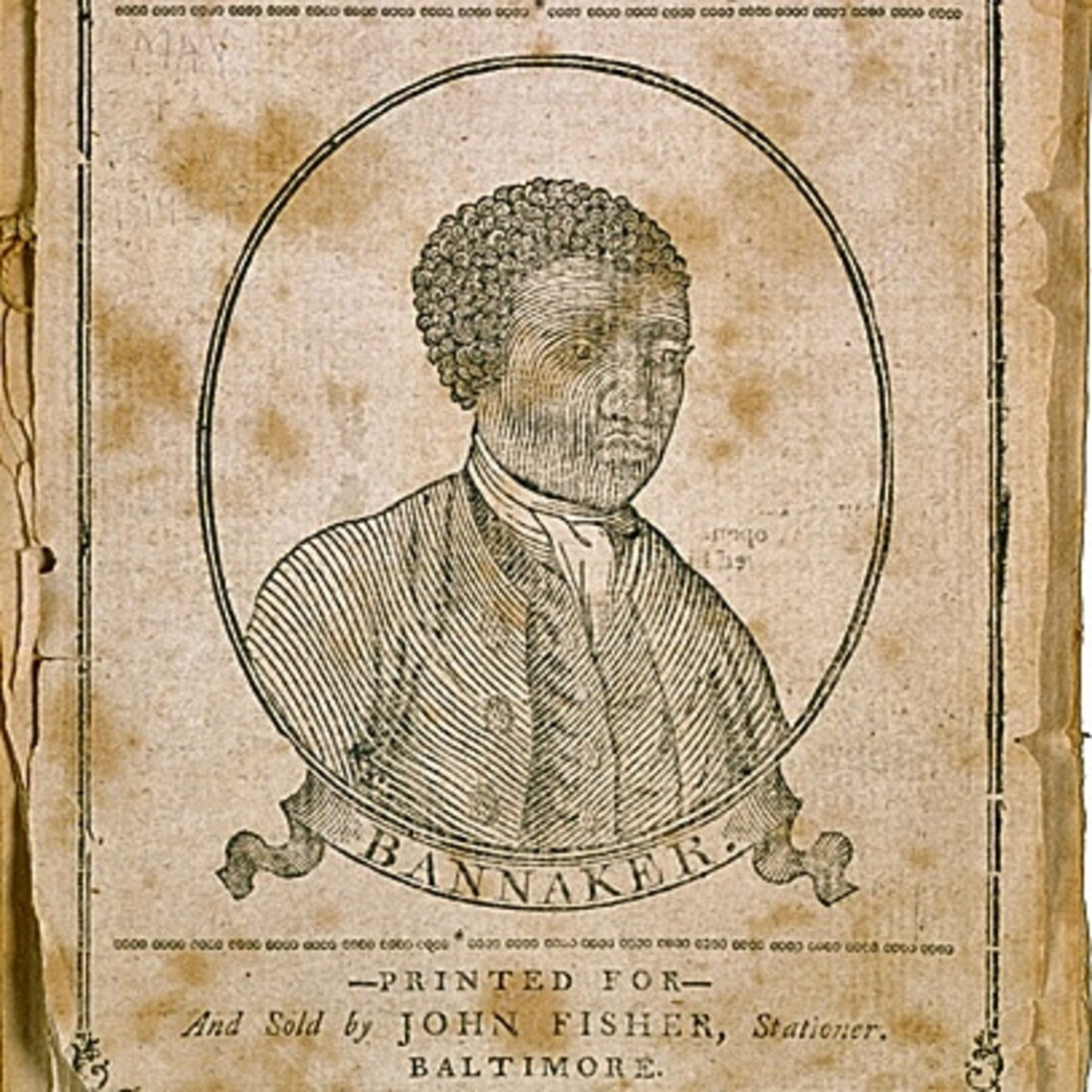

On August 19, 1791, the free-born African American scientist and astronomer Benjamin Banneker wrote to Thomas Jefferson to challenge Jefferson’s contention that Black people were inferior to White people. Banneker cited the American Revolution and the Declaration of Independence to argue that slavery was wrong, largely because it robbed people of their natural equality. On August 30, 1791, Jefferson responded, “no body wishes more ardently to see a good system commenced for raising the condition” of enslaved people.

Sir, suffer me to recall to your mind that time, in which the arms and tyranny of the British crown were exerted, with every powerful effort, in order to reduce you to a state of servitude . . . You were then impressed with proper ideas of the great violation of liberty, and the free possession of those blessings, to which you were entitled by nature . . . how pitiable is it to reflect . . . in detaining by fraud and violence so numerous a part of my brethren, under groaning captivity and cruel oppression, that you should at the same time be found guilty of that most criminal act, which you professedly detested in others.

—Benjamin Banneker to Thomas Jefferson, August 19, 1791

Following the Revolution, only White men who owned property were allowed to vote. But poor White men used protests and petitions to insist that they deserved equal suffrage rights. Nearly all White men in the United States gained full citizenship rights by 1856.

The rights of suffrage are to a free people, what the rights of conscience are to individuals; and neither can be infringed or attacked, without violating the laws of nature and the inherent privileges of man.

—[Anonymous], Rights of Suffrage, Hudson, NY, Ashbel Stoddard, 1792

Display Full Image

Enslaved and free Black people recognized the contradiction between slavery and the liberty and equality that the Declaration of Independence promised. In petitions, letters, and lawsuits, they exposed the limits of natural rights philosophy. They never stopped fighting to end slavery and gain their freedom.

Prince Hall, portrait printed in Joseph A. Walkes, Jr., Black Square & Compass: 200 Years of Prince Hall Freemasonry (Richmond, Virginia: Macoy, 1981).

Display Full Image

For White women, the American Revolution painfully exposed their unequal status. Although they tirelessly supported the Revolution, they were generally denied suffrage or access to office-holding and equal rights. Beginning in 1869, women began to receive voting rights at the state and municipal level. The women’s suffrage amendment would not be ratified until 1919, almost 150 years after the Declaration.

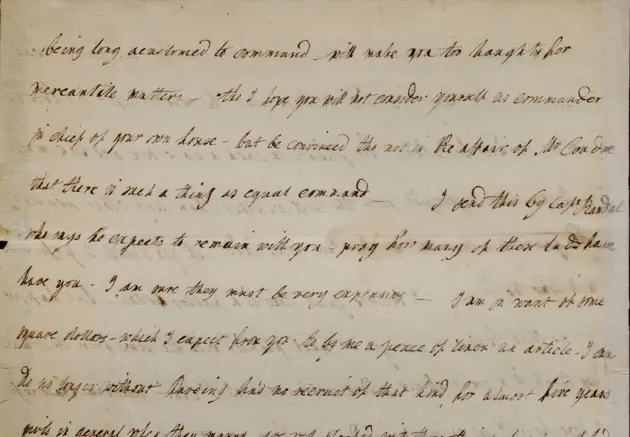

Lucy Flucker Knox to her husband, General Henry Knox, August 23, 1777. (The Gilder Lehrman Institute, GLC02437.00638)

Display Full Image

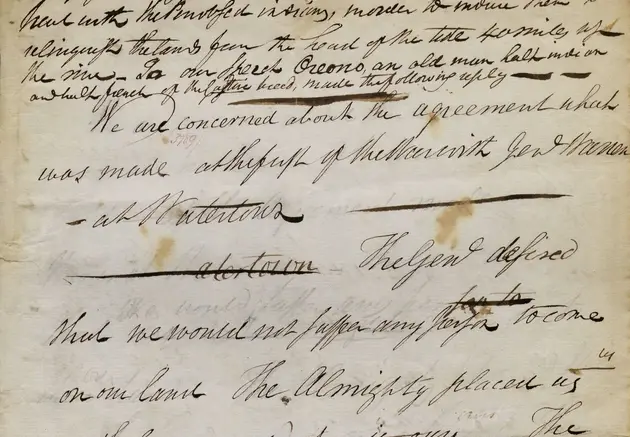

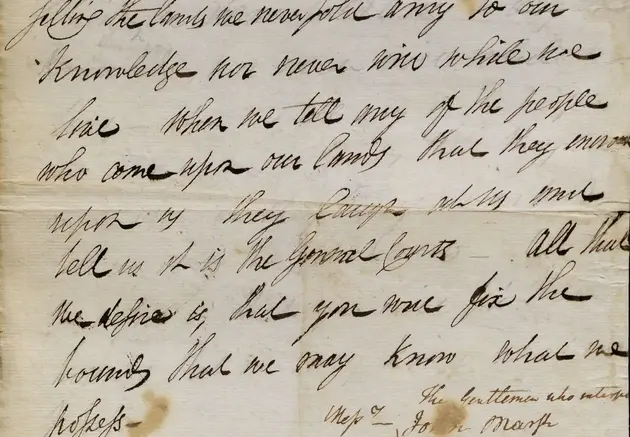

Long before the American Revolution, colonial settlers had been seizing Indigenous peoples’ land and violating their sovereignty. Following the Revolution, the situation worsened, as newly independent White Americans rapidly expanded settlements on Indigenous land. Indigenous peoples strongly protested against encroachment, insisting on their right to freedom and sovereignty.

Document recording the result of negotiations between Henry Knox, Benjamin Lincoln, and the Penobscot Indians, 1784. (The Gilder Lehrman Institute, GLC02437.03046)

Display Full Image

Penobscots objected to White settlement on their land. As articulated by one Penobscot man whom Henry Knox and Benjamin Lincoln encountered: “The Almighty placed us on the land and it is ours . . . The General said that no person should interfere and take any of our lands . . . Now why should we not hold the Lands as the Almighty gave them to us.”

Document recording the result of negotiations between Henry Knox, Benjamin Lincoln, and the Penobscot Indians, 1784. (The Gilder Lehrman Institute, GLC02437.03046)

I hope you will not consider yourself as commander in chief of your own house—but be convinced . . . that there is such a thing as equal command.

—Lucy Flucker Knox to Henry Knox, August 23, 1777

Domestic Legacies

We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men and women are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness; that to secure these rights governments are instituted, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.

—Declaration of Sentiments, 1848

In the decades after independence, the ideals of the Declaration of Independence were still not fully realized for all Americans. Native Americans continued to assert their sovereignty and resist land incursion from the United States. Citing the language of the Declaration of Independence, some groups of Americans sought to abolish slavery and expand women’s rights. In the wake of the Civil War, protests by those who faced political oppression, legal restrictions, or customary exclusion grew louder. They resisted the violent dispossession of Native American lands, racial discrimination against Black citizens, and immigration policies that excluded certain nationalities. They attempted to turn the Declaration’s promise of equality into reality.

Display Full Image

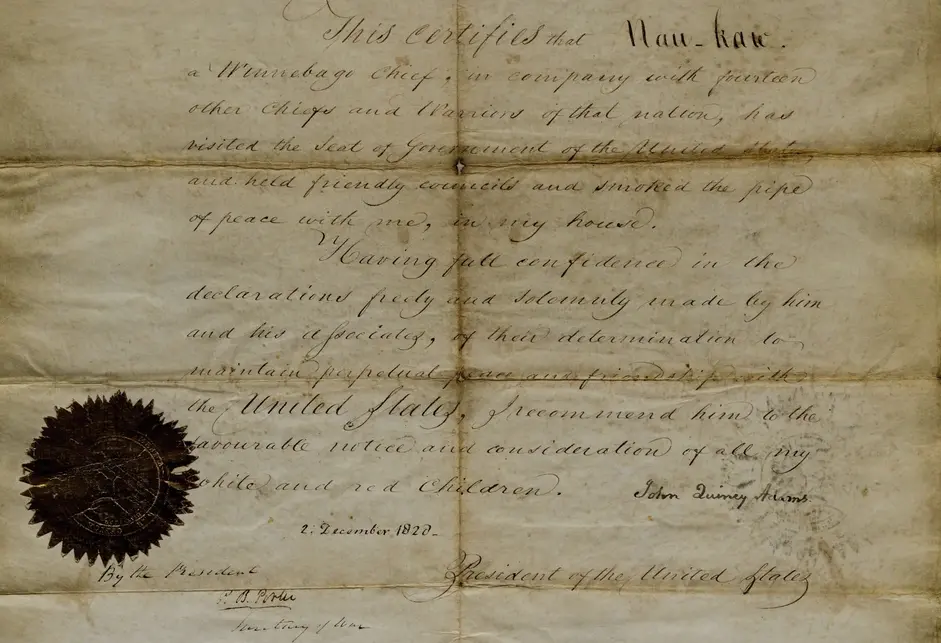

Indigenous peoples continually asserted their sovereignty following the end of the Revolutionary War. They demanded recognition that their nations were diplomatic equals of the United States. Native Americans’ lands remained under threat and, to protect their rights as sovereign nations, diplomatic delegations of Indigenous leaders traveled frequently to meet with American officials. Through savvy negotiation, they strove to preserve self-government and self-determination.

Certification of peace between John Quincy Adams and Naw-kaw, Winnebago Chief, December 2, 1828. (The Gilder Lehrman Institute, GLC05120.01)

Display Full Image

Women active in the temperance, dress reform, and abolitionist movements met at Seneca Falls, New York, in 1848 to advocate for women’s rights. These activists demanded suffrage, improved educational access, an end to coverture, property rights, and access to the ministry. The Declaration of Sentiments used the language of the Declaration of Independence to signal that women were equally American, and thus deserved equal rights.

The print Representative Women depicts a group of leaders in the fight for women’s suffrage. Clockwise from the top, they are Lucretia Coffin Mott, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Mary Livermore, Lydia Maria Francis Child, Susan B. Anthony, Sara Jane Lippincott and, at the center, Anna Elizabeth Dickenson. Representative Women, lithograph by L. Schamer. Boston: L. Prang and Co., ca. 1870. (Library of Congress)

Display Full Image

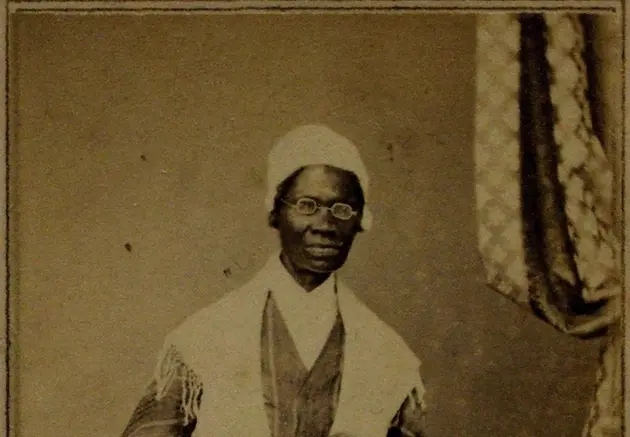

Black women played a significant role in resisting slavery. Some, like Maria Stewart, Sojourner Truth, and Harriet Jacobs shared their stories in essays, speeches, and narratives, and advocated for abolition. Others, like Harriet Tubman and Harriet Bell Hayden, aided fugitives from slavery on their journey to freedom.

Sojourner Truth, 1864. (The Gilder Lehrman Institute, GLC06391.20)

Display Full Image

On January 1, 1863, the Emancipation Proclamation not only ended slavery in Confederate states but also allowed African American men to join the US Army. Many African Americans saw military service as a way to demonstrate their readiness for freedom and equality. Both Black men and women supported the war effort and many self-emancipated by fleeing to Union Army camps. Black soldiers used their wages to build communities: schools, churches, and land purchases were all priorities.

Freedom to the Slave, print published to recruit African Americans for military service, 1863. (The Gilder Lehrman Institute, GLC04198)

Display Full Image

While the abolition of slavery brought freedom to millions of African Americans, it remained unclear in 1865 at the end of the American Civil War who was and who was not a full citizen of the United States. During the debates about the Fourteenth Amendment that granted formerly enslaved people citizenship in 1868, anti-Chinese immigration advocates explicitly sought to exclude Chinese people from eligibility to even come to America. Native Americans were not universally considered citizens of the United States until 1924. Exclusive immigration policies that barred Chinese and most Asian immigrants from the country did not change until the passage of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965.

The Airing, Chinatown, San Francisco, photograph by Arnold Genthe, ca. 1900. (Library of Congress)

Global Legacies

From Eurasia to Africa to the Americas, there have been more than 100 declarations of independence since 1776, as well as additional declarations of rights. The US Declaration offered a globally recognized model for how to announce changes in sovereignty. Yet it was not universally embraced by revolutionaries. Many people in other new nations saw it as irrelevant to local circumstances. Others found it too exclusionary. For example, in the early nineteenth century, Haiti, Mexico, and Colombia experimented with antislavery declarations of independence that made even greater promises to protect equality. Just as the US Declaration influenced the world, the world influenced the Declaration’s legacy at home. Perhaps “all men are created equal” could be enacted even more fully.

American democracy inspired the French Revolution in 1789. But France’s steps toward equality soon surpassed those of the United States. In turn, the French Revolution’s violent radicalization led observers worldwide to reexamine their own governments, and to ask how much equality was too much. Thomas Jefferson was serving as US minister to France when the revolution began. He tried to shape France’s Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen, but his influence was marginal.

In the same way that French people revolted against monarchy, enslaved people in the colonial French Caribbean revolted against slavery. The result was the abolitionist nation of Haiti, which declared independence in 1804 and gradually broadened global understandings of human rights. Haiti’s example terrified enslavers while inspiring abolitionists and enslaved people in the United States and around the world.

In the 1810s and 1820s, colonies in North and South America shook off colonial rule. Most of the new nations pursued limited antislavery reforms and enfranchised men of African and Indigenous descent. In the United States, abolitionists used the example set by former Spanish colonies to argue that multiracial republics were possible.

As the nineteenth-century Americas became a hub of democratic innovation, European revolutionaries struggled. France had a dictator, Napoleon, by 1802 and restored its monarchy in 1814. Greece invoked global revolutionary traditions upon declaring independence from the Ottoman Empire in 1822 but soon became a conservative monarchy. Hierarchy proved difficult to completely set aside. Europeans—and their African and Asian colonies—would issue more declarations of independence in the twentieth century.

Display Full Image

Spanish American revolutionaries developed a rhetoric of inclusive nationalism and racial harmony. In reality, equality remained a contested ideal, and slavery persisted for decades despite partial reforms. Inhabitants of Antioquia [Colombia], watercolor by Henry Price, 1852. (Library of Congress)

Display Full Image

Since American independence, Indigenous nations have appealed to legal authorities to protect their sovereignty. The United Nations Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, adopted in 2007, is one outcome of their advocacy.

Deskaheh Levi General was a Cayuga leader who traveled to Switzerland in 1923 as a spokesman for the Haudenosaunee Confederacy. He urged the League of Nations (a predecessor of the United Nations) to recognize Haudenosaunee government. Deskaheh Levi General, 1923. (Collection of Cleveland General)

Coda

As David Armitage, historian of the global impact of the Declaration writes, “the US Declaration of Independence created both an encouraging example and an elusive ideal for later self-determination movements. . . . Over time and around the world, the US Declaration increasingly came to animate and inspire other movements for self-determination. Of the 193 states currently represented at the United Nations, more than half have a document considered as a declaration of independence. The US Declaration was the first.”

Credits

Funding provided by the National Endowment for the Humanities*

*Any views, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this exhibition do not necessarily represent those of the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Project Director: Denver Brunsman, Associate Professor and Chair, Department of History, George Washington University

Scholarly Advisors

- Leslie M. Alexander, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Professor of History, Rutgers University

- Caitlin Fitz, Associate Professor of History, Northwestern University

- Vanessa M. Holden, Associate Professor of History, Director of African American and Africana Studies, and Director of the Central Kentucky Slavery Initiative, University of Kentucky

- Benjamin H. Irvin, Associate Professor of History and Executive Editor of the Journal of American History, Indiana University

- Alyssa Mt. Pleasant, Assistant Professor of Native American Studies, University at Buffalo (SUNY)

- Eric Slauter, Associate Professor of English, Deputy Dean of the Humanities Division, and Master of the Humanities Collegiate Division, University of Chicago

- Rosemarie Zagarri, Distinguished University Professor of History, George Mason University