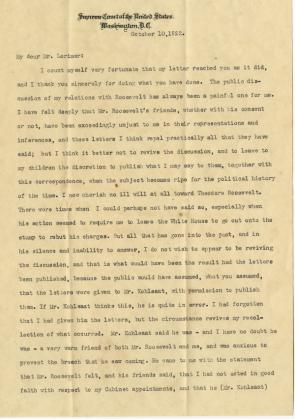

William H. Taft recalls dispute with Theodore Roosevelt, 1922

A Spotlight on a Primary Source by William H. Taft

As tensions built up between Taft and Roosevelt before the election of 1912, former newspaper editor Herman Henry Kohlsaat convinced Taft to give him copies of the correspondence Roosevelt sent to Taft. Taft claimed that Kohlsaat never intended to publish the correspondence, but only wanted to use it to heal the breach between Roosevelt and Taft. However, ten years later, the letters came to the attention of George H. Lorimer, editor of the Saturday Evening Post, who did consider publishing them.

As this letter indicates, Taft persuaded Lorimer not to publish the correspondence, even though the letters would have vindicated Taft. Three years after Roosevelt’s death, Taft wrote, "I now cherish no ill will at all toward Theodore Roosevelt," and expressed his wish "to leave to my children the discretion to publish what I may say to them, together with this correspondence, when the subject becomes ripe for the political history of the time." The letter is an example of the close, collaborative, and even confidential relationship that sometimes prevailed between politicians and the press.

Excerpt

William Howard Taft to George Lorimer, October 10, 1922

I count myself very fortunate that my letter reached you as it did, and I thank you sincerely for doing what you have done. The public discussion of my relations with Roosevelt has always been a painful one for me. I have felt deeply that Mr. Roosevelt’s friends, whether with his consent or not, have been exceedingly unjust to me in their representations and inferences, and these letters I think repel practically all that they have said; but I think it better not to revive the discussion, and to leave to my children the discretion to publish what I may say to them, together with this correspondence, when the subject becomes ripe for the political history of the time. I now cherish no ill will at all toward Theodore Roosevelt. There were times when I could perhaps not have said so, especially when his action seemed to require me to leave the White House to go out onto the stump to rebut his charges. But all that has gone into the past, and in his silence and inability to answer, I do not wish to appear to be reviving the discussion, and that is what would have been the result had the letters been published, because the public would have assumed, what you assumed, that the letters were given to Mr. Kohlsaat, with permission to publish them.