Alice Paul, Suffrage Militant

by Barbara Winslow

Alice Stokes Paul (1885−1977) was one of the leading feminists of the early twentieth century, a person who brought the women’s suffrage movement into the national spotlight. Passage of the Susan B. Anthony Amendment or the Nineteenth Amendment to the US Constitution was due in large part to Paul’s visionary leadership, courage, determination, brilliant organizational skills, and laser-like focus on planning and execution. A tireless, unrelenting, uncompromising, and uncomplaining feminist fighter, she fervently believed that there could be no gender equality until and unless the nation was committed to women’s suffrage and to an Equal Rights Amendment to the Constitution.

Alice Stokes Paul (1885−1977) was one of the leading feminists of the early twentieth century, a person who brought the women’s suffrage movement into the national spotlight. Passage of the Susan B. Anthony Amendment or the Nineteenth Amendment to the US Constitution was due in large part to Paul’s visionary leadership, courage, determination, brilliant organizational skills, and laser-like focus on planning and execution. A tireless, unrelenting, uncompromising, and uncomplaining feminist fighter, she fervently believed that there could be no gender equality until and unless the nation was committed to women’s suffrage and to an Equal Rights Amendment to the Constitution.

The history of suffrage in the United States has always been complicated and contested. Before the ratification of the Constitution, propertied women could vote in two colonies, New Jersey and Massachusetts. But after the ratification of the Constitution, eligibility to vote in the United States was established both through the federal constitution and by state law. The Constitution as originally written did not establish any such rights during the period from 1787 to 1870. In the absence of a specific federal law or constitutional provision, each state was given considerable discretion to establish qualifications for suffrage and candidacy within its own respective jurisdiction. In addition, states and lower-level jurisdictions established election systems, such as at-large or single member district elections for county councils or school boards. Class, race, age, ethnicity, gender, nationality, and even religion were once qualifications for the vote.

The demand for women’s suffrage began in July 1848 at the Seneca Falls, New York, Women’s Rights Convention. Elizabeth Cady Stanton drafted the resolution. Frederick Douglass, the escaped slave and leading abolitionist, introduced the resolution, writing, “It is the duty of the women in this country to secure for themselves their sacred right to the elective franchise.” From 1848 until the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861, feminists campaigned for a number of women’s rights reforms including the right to vote. Campaigns for women’s suffrage were halted during the war, and took on new directions when hostilities ceased in 1865.

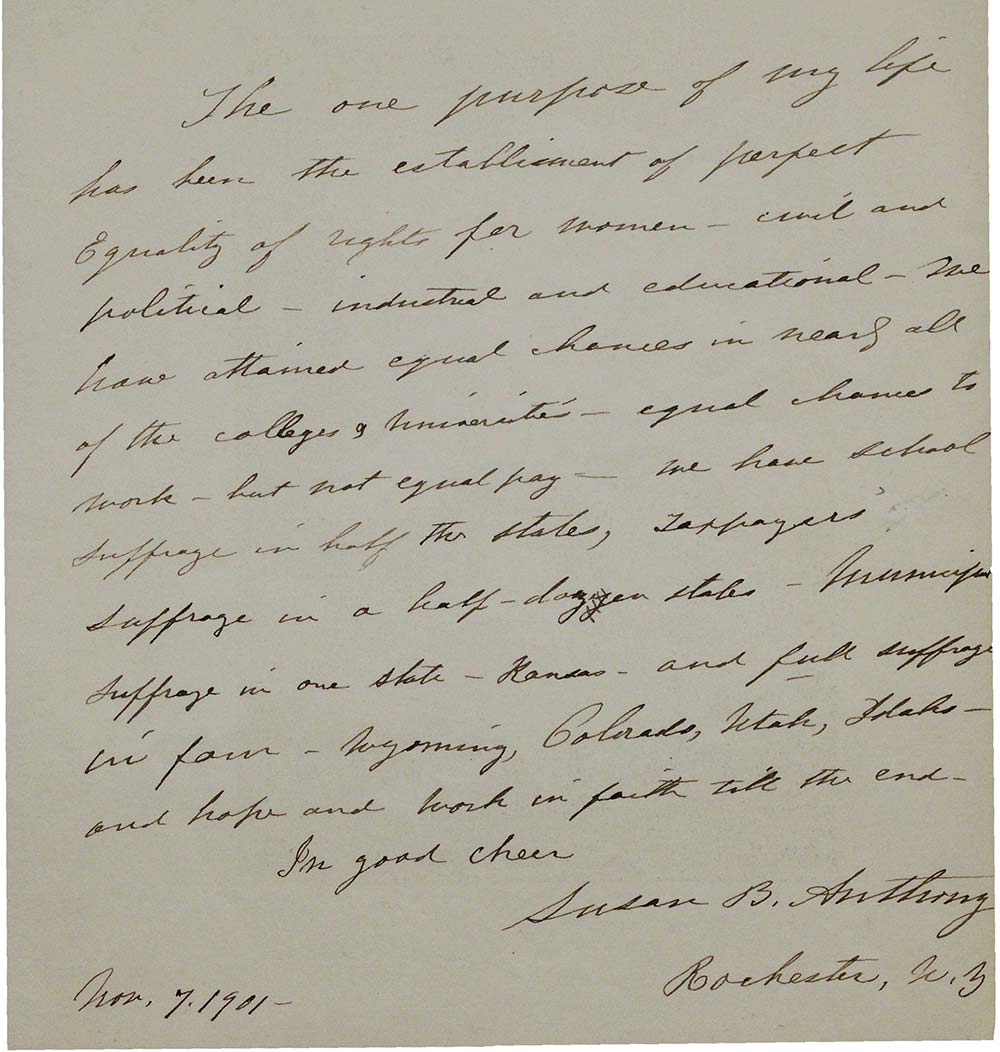

After the Civil War, the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the Constitution set the stage for a deep and long-lasting split in the radical abolitionist/feminist/women’s suffrage movement. The Fourteenth Amendment, ratified in 1868, defined citizenship as male, and the Fifteenth Amendment gave the right to vote to African American men. One group of suffragists, including Lucy Stone and Frederick Douglass, supported the Fifteenth Amendment; another group, including Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, and Sojourner Truth, opposed its passage for its exclusion of women. The split weakened the feminist movement for thirty years. Beyond the 1870s suffragists often used racist and xenophobic arguments to make their case. Why should immigrant and African American men be allowed the franchise when it is denied to white middle class educated women? The charge of suffrage racism is one with which feminist activists must deal even today.

From 1869−1890, there were two warring suffrage organizations. The first, the American Women’s Suffrage Organization, headed by Lucy Stone, tended to be moderate, focusing on strategies of state referendums. The second, the National Women’s Suffrage Organization, led by Stanton and Anthony, took up a range of other women’s issues as well as the demand for a federal amendment to the US Constitution.  There were a number of women’s suffrage victories in western states (Wyoming, Utah, Colorado) from 1868 to 1900, but for the most part the struggle for the vote was in the doldrums.

There were a number of women’s suffrage victories in western states (Wyoming, Utah, Colorado) from 1868 to 1900, but for the most part the struggle for the vote was in the doldrums.

Alice Paul was born during the suffrage doldrums to Quaker parents who supported gender equality. As a young girl, she went to women’s suffrage meetings with her mother and father. She attended Swarthmore College, a Quaker institution near Philadelphia. (Lucretia Mott—abolitionist, feminist, and organizer of the 1848 Seneca Falls convention—was Swarthmore’s first president.) Graduating in 1905, Paul pursued advanced degrees in social work while working at New York City’s Rivington Street Settlement. In 1907 she was awarded a prestigious fellowship to further her studies in England.

It was in England that Paul met up with the militant suffrage organization, the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU). The WSPU was founded in 1903 by Emmeline Pankhurst and her three daughters, Christabel, Sylvia, and Adela. Two years later, the WSPU started employing militant tactics, that is, heckling politicians, organizing suffrage processions, participating in mass civil disobedience, and holding the political party in power responsible for failure to give women the vote. In 1909 Paul met Lucy Burns, a fellow American suffragist. They became close friends and comrades in England and remained so throughout the campaign in the United States. Both women engaged in confrontational militancy. At one demonstration against the Lord Mayor of London, Paul, dressed as a cleaning woman, climbed up into the rafters of the meeting hall in order to escape detection. As soon as the Lord Mayor started speaking, Paul let loose women’s suffrage leaflets and shouted, “Votes for Women.” Lucy Burns, sitting in the audience, also heckled. Both were arrested. In London Paul and Burns participated in suffrage parades, enduring arrest, hunger strikes, and the horrors of forced feeding. Recognizing Paul’s skills, Emmeline Pankhurst invited her to take a position as a full-time paid WSPU organizer—an opportunity few were offered. But Paul, her health compromised by the hunger strikes and forced feedings, returned to New York in 1910. Her experience in the WSPU was invaluable training for the suffrage struggles in the US. She had become an expert organizer of rallies and demonstrations; she knew how to best petition men in power; and she developed political strategies for effectively dealing with political bureaucracies. Paul’s experiences in England tested her bravery and the strength of her convictions. Undaunted, she faced hostile men, aggressive police, jails, and forced feeding. The intensity of the WSPU forged unbreakable bonds of courageous sisterhood, which remained through the rest of her life.

Paul arrived in the United States at the time when a new generation of suffrage leaders emerged, including Elizabeth Stanton’s daughter Harriot Stanton Blatch, the historian Mary Ritter Beard, and the playwright and actress Elizabeth Robins, all from the WSPU school of suffrage politics. The main women’s suffrage organization, the National American Women’s Suffrage Association (NAWSA)—which merged the NWSA and the AWSA—was clearly flailing; it suffered from loss of membership, lack of money, and what appeared to be a losing strategy of state-by-state referendum campaigns. Almost immediately Paul appeared on the NAWSA suffrage circuit speaking about militancy, suffrage, and the Pankhursts. Paul chafed at the timidity of NAWSA’s approach. She believed its leadership was too frightened at the prospect of suffrage militancy, too conciliatory to anti-suffrage politicians, and too committed to the strategy of costly and time-consuming state-by-state electoral referendums. Taking her cue from the WSPU, she argued that NAWSA must hold the political party in power—after 1912, the Democratic Party—responsible for the passage of women’s suffrage. She believed a focused and militant approach to the passage of a federal amendment to the Constitution was the most effective path for the winning vote. Heading up a NAWSA committee, she pursued her agenda by enlisting sympathetic suffragists such as the socialist-feminist Crystal Eastman, the socialite Alva Belmont, Inez Milholland, and Mary Ritter Beard.

In 1913 Paul achieved recognition, praise, and notoriety for organizing the first national women’s suffrage parade in Washington DC. The march down Pennsylvania Avenue spotlighted her demand for a federal amendment to the Constitution. Putting pressure on the newly elected Democratic president, Woodrow Wilson, the march took place the day before Wilson’s inauguration. She wanted, and delivered, a dramatic spectacle. Inez Milholland, dressed as Joan of Arc, rode a white horse at the head of the parade. There were more than 8000 marchers carrying purple, gold, and white banners; twenty-six floats; ten marching bands; statewide contingents; and delegations of professors, students, nurses, actresses, social workers, and musicians. Five hundred thousand spectators lined Pennsylvania Avenue to watch the suffragists.

Like Susan B. Anthony, Paul had one focus: women’s suffrage. And, for Paul as for Anthony, no other issue could interfere with the demand for the vote. One result of this approach was that the women’s suffrage movement did nothing to challenge the racism and xenophobia of the Progressive Era. In fact, one might argue, suffragists aided and abetted racism and xenophobia. Paul had no personal or political objection to the involvement of black women in suffrage parades. But when white delegations from the Jim Crow South protested the possible participation of African American women in the march, she thought she defused the situation by having members of Howard University’s newly established African American sorority, Delta Sigma Theta, march at the back of the parade. Moreover, like Anthony in the nineteenth century, Paul downplayed the role of immigrant and trade union women in order to mollify middle-class, white Protestant suffragists. This is one of the unrecognized aspects of the women’s suffrage movement, one which contemporary feminists must acknowledge.

Halfway into the march, male spectators began to heckle, throw garbage, and actively attack suffragists. The police did nothing. Only the Boy Scouts intervened on behalf of the women. In spite of the riot the parade was a triumph. On March 4, 1913, the New York Times commented that the march was “one of the most impressively beautiful spectacles ever staged in this country.” Woodrow Wilson, on the other hand, was furious. When he arrived at the nation’s capital, there was no one there to greet him. “Where are all the people?” an aide asked. “Over on the Avenue watching the suffrage parade.”[1]

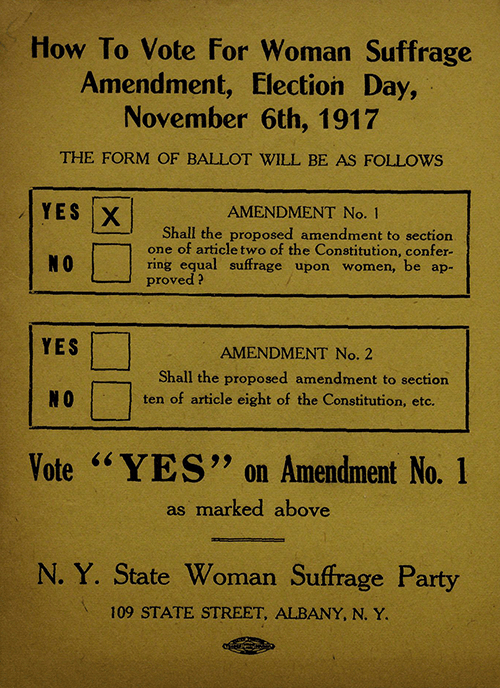

Immediately afterward Paul and Burns knew that they needed their own national organization, separate from NAWSA. They created the Congressional Union (CU) and put out their own newspaper, The Suffragist. The CU announced that it would campaign against Democrats, and went into women’s suffrage states to win women voters to their cause. NAWSA was not able to compete with the CU in terms of membership, money, or lobbying efforts. The work of the CU paid off. In March 1914 a woman’s suffrage bill reached Congress. According to the preeminent suffrage historian Eleanor Flexner, who was not particularly sympathetic to the Congressional Union, Congress finally took up women’s suffrage “because of the activity of the Congressional Union; of this there can be no doubt.”[2] The CU became the National Women’s Party (NWP) in 1916.

The First World War shook up the women’s suffrage movement. Many, if not most, of the activists were peace activists to varying degrees. But supporting one’s nation in a time of war took precedence over desires for peace or the vote. In an attempt to appease Wilson’s insistence on 100 percent support for the war, NAWSA supported the war, served on national war boards, and denounced their pacifist sister suffragists. Paul, maintaining her single-issue focus, announced that the NWP would take no position on the war, and would continue its militant advocacy for a federal women’s suffrage amendment.

Opposing entry into the war was Jeannette Rankin from Montana, the first woman elected to Congress. A socialist, feminist, pacifist, and suffragist, Rankin was caught between the two factions of the suffrage movement as represented by Alice Paul and Carrie Chapman Catt, the president of NAWSA. Catt put pressure on Rankin, threatening that a nay vote would set suffrage back twenty years. Paul also contacted Rankin, telling her that the NWP had taken no position on the war, and would support her regardless of her vote. True to her principles, Rankin voted to oppose the war. Catt never forgave her and endorsed Rankin’s male opponent when she ran for the Senate in 1918. (Between the two wars, Rankin continued her pacifist, feminist, socialist activism. She was reelected to the House in 1940 and cast the only no vote against America’s entry into World War II.) Rankin later reflected that Paul’s support was the “only support I received from women in my vote.”[3]

Opposing entry into the war was Jeannette Rankin from Montana, the first woman elected to Congress. A socialist, feminist, pacifist, and suffragist, Rankin was caught between the two factions of the suffrage movement as represented by Alice Paul and Carrie Chapman Catt, the president of NAWSA. Catt put pressure on Rankin, threatening that a nay vote would set suffrage back twenty years. Paul also contacted Rankin, telling her that the NWP had taken no position on the war, and would support her regardless of her vote. True to her principles, Rankin voted to oppose the war. Catt never forgave her and endorsed Rankin’s male opponent when she ran for the Senate in 1918. (Between the two wars, Rankin continued her pacifist, feminist, socialist activism. She was reelected to the House in 1940 and cast the only no vote against America’s entry into World War II.) Rankin later reflected that Paul’s support was the “only support I received from women in my vote.”[3]

Paul inaugurated the first-ever protest in front of the White House. Called the “Silent Sentinels,” suffragists picketed the White House with banners reading, “Mr. President What Will You Do for Woman Suffrage,” before the US entered the war in 1917. In spite of wartime patriotism, suppression of speech, jailing, and deportation of antiwar protestors, NWP pickets continued at the White House demanding women’s right to vote. In June 1917, picketers were arrested on charges of “obstructing traffic.” Over the next six months, many, including Paul, were convicted and incarcerated at the Occoquam Workhouse in Virginia. After a public outcry, Wilson pardoned the women, but suffragists continued to picket and to be arrested and sent to jail. Offended, Wilson offered no more pardons. In solidarity with other activists in her organization, Paul purposefully strove to receive a seven-month jail sentence that started on October 20, 1917. Whether sent to Occoquan or the District Jail, the women were given no special treatment as political prisoners and had to live in harsh conditions with poor sanitation, infested food, and dreadful facilities. Protesting the brutal and inhumane conditions, Paul went on a hunger strike and was forcibly fed. Prison authorities beat imprisoned suffragists, one of whom was Dorothy Day, later associated with the Catholic Worker, in an incident known as “The Night of Terror.” More than 500 women were arrested, 168 served time, and dozens were force-fed and tortured.[4]

Paul’s tactics had worked. Wilson promised to release all suffrage prisoners and support a federal women’s suffrage amendment. The war brought out the worst in the Wilson administration, denying citizens their civil rights and subjecting them to unlawful torture and imprisonment. NAWSA did not fare well either.  In an attempt to curry favor with the administration, it condemned the picketers, failed to defend the free-speech rights or protest the brutal treatment of sister suffragists, and supported male politicians over female antiwar suffragists.

In an attempt to curry favor with the administration, it condemned the picketers, failed to defend the free-speech rights or protest the brutal treatment of sister suffragists, and supported male politicians over female antiwar suffragists.

Wilson was true to his word, and on January 10, 1918, the House of Representatives voted in favor of a federal amendment; on June 4, 1919, the Senate voted in favor. Immediately the states began the process of ratification. This time, there was little organized anti-suffrage activity. Women’s participation in the war effort had swung public opinion in favor of women’s suffrage. Tennessee was the last state to vote, and on August 26, 1920, the Anthony Amendment became the Nineteenth Amendment to the US Constitution.

One would think that after ten years of organizing, picketing, demonstrating, going to jail, hunger striking, and enduring forced feeding, Alice Paul would have been worn out. But after a rest to recoup her health, she again took charge of the National Women’s Party. In 1921, she and Crystal Eastman drafted another constitutional amendment, this one known as the Lucretia Mott or Equal Rights Amendment. It read, “Men and women shall have equal rights throughout the United States and every place subject to its jurisdiction. Congress shall have the power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.” For Paul, this Equal Rights Amendment was the logical progression for women’s equality. But times and politics had changed. The overwhelming majority of progressive women and suffragists opposed an ERA because it would eradicate women’s progressive legislation, laws enacted, at the time, to better women’s working conditions. The ERA was opposed by almost every progressive, civil rights, feminist, and trade union organization until the 1970s. A campaign for an ERA won a number of states in the mid-1970s, but stalled and failed as part of the growing conservative backlash. Paul, who continued to struggle for an ERA, lived to see the revival of feminism in the sixties and seventies.

Paul’s leadership of the suffrage and feminist movements illustrates her tremendous strengths. The 1913 women’s suffrage demonstration almost presages the January 21, 2017, Women’s March—public, confrontational, with pink pussy-cat hats instead of gold, white, and purple banners. Paul was single minded and tactically savvy, and knew how to mobilize public opinion for her cause. She saw herself as a servant leader committed to women’s rights. She certainly deserves praise for galvanizing the women’s suffrage movement. There is little doubt that Paul’s suffrage organization and tactics forced the Democrats to introduce the Nineteenth Amendment. But Paul’s singlemindedness led her to unnecessary confrontations with, and later isolation from, sister suffragists. Her focus on a single issue and her individualistic approach to women’s emancipation led her to ignore or dismiss the impact of class, race, and ethnicity on women’s living experiences. For all the limitations of an Equal Rights Amendment, it would be better if one became constitutional; and if an ERA ever passes, I hope it would be renamed the Mott/Paul Equal Rights Amendment.

[1] Inez Hayes Irwin, Up the Hill with Banners Flying: The Story of the Woman’s Party (Penobscot ME: Traversity Press, 1964), 31.

[2] Eleanor Flexner and Ellen Fitzpatrick, A Century of Struggle: The Women’s Rights Movement in the United States (Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1996), 262.

[3] Quoted in Christine Lunardini, Alice Paul: Equality for Women (Boulder CO: Westview Press, 2013), 120.

[4] Katherine H. Adams and Michael L. Keene, Alice Paul and the American Women’s Suffrage Campaign (Champaign-Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2008), 191–214.

Barbara Winslow is Professor Emerita of History at Brooklyn College. An authority on women’s activism, she is the founder and director emerita of the Shirley Chisholm Project. Her recent publications include Shirley Chisholm: Catalyst for Change (Westview Press, 2013) and Clio in the Classroom: A Guide for Teaching US Women’s History (Oxford University Press, 2009).