A Founding Father on the Missouri Compromise, 1819

A Spotlight on a Primary Source by Rufus King

In 1819 a courageous group of Northern congressmen and senators opened debate on the most divisive of antebellum political issues—slavery. Since the Quaker petitions of 1790, Congress had been silent on slavery. That silence was shattered by Missouri’s request to enter the Union as a slave state, threatening to upset the tenuous balance of slave and free states. The battle to prevent the spread of slavery was led by a forgotten Founding Father: the Federalist US senator from New York, Rufus King.

In 1819 a courageous group of Northern congressmen and senators opened debate on the most divisive of antebellum political issues—slavery. Since the Quaker petitions of 1790, Congress had been silent on slavery. That silence was shattered by Missouri’s request to enter the Union as a slave state, threatening to upset the tenuous balance of slave and free states. The battle to prevent the spread of slavery was led by a forgotten Founding Father: the Federalist US senator from New York, Rufus King.

When the Missouri debates began, King was completing a third term as US senator and was one of the most respected statesmen in America. As a signer of the Constitution, a former ambassador to Great Britain, and a candidate for president in 1816, his political career gave him a unique standing from which to lead the debates against expanding the institution of slavery.

The dispute over Missouri’s status began in February 1819 when Representative James Tallmadge Jr. of New York proposed an amendment to prohibit slavery in Missouri. His proposal would allow for the gradual emancipation of slaves in the territory. When the bill was sent to the Senate, King supported Tallmadge’s amendment in an uphill battle.

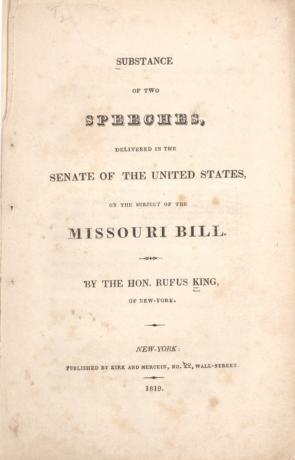

The Senate debates were not recorded, but the substance of King’s argument was preserved in a pamphlet on the Substance of Two Speeches . . . on the Subject of the Missouri Bill that he prepared at his estate in Jamaica, Long Island. Using the formal tone and logical arguments of a lawyer, as well as his authority as one of the few remaining members of the Senate who had signed the Constitution, King made a case that the power of Congress included the right to regulate the conditions of new states, including the restriction of slavery. In his view, the Tallmadge amendment fell safely within the bounds of Congress’s mandate. King believed that federal regulation trumped the interests of local slaveholders. If the power to create the laws of a new state were left to slaveholders, slavery as an institution would never fade away.

King insisted that the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, a proposal that he was instrumental in shepherding through the Confederation Congress, provided a precedent for Congressional action in the territories. The sixth article of the ordinance, which every southern state had approved, prohibited slavery in what would eventually become the states of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, and Wisconsin. Referencing Congress’s power, of which he had a unique understanding because he had helped create it, King said, "Congress may therefore make it a condition of the admission of a new state, that slavery shall be forever prohibited within the same."

Despite their efforts, King and his allies were defeated. The famous Missouri Compromise was passed in March 1820. Missouri was to be given slave state status and Maine, a former district of Massachusetts, to be declared as a free state to preserve the Congressional balance. Another provision stated that, with the exception of Missouri, slavery was to be excluded from the lands of the Louisiana Purchase north of latitude 36° 30'. Despite losing this battle, King and his supporters were able to set the benchmark that future anti-slavery advocates would reach for and eventually surpass. In the coming decades, the sectional conflict over slavery that had been brought forth during the Missouri controversy would eventually lead to civil war.