The Reconstruction Amendments: Official Documents as Social History

by Eric Foner

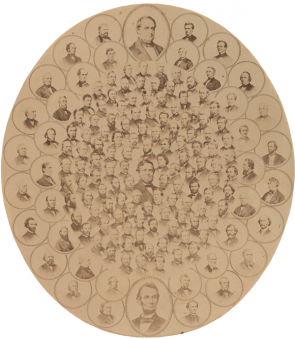

On June 13, 1866, Thaddeus Stevens, the Republican floor leader in the House of Representatives and the nation’s most prominent Radical Republican, rose to address his Congressional colleagues on the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution. Born during George Washington’s administration, Stevens had enjoyed a career that embodied, as much as any other person’s, the struggle against slavery and for equal rights for black Americans. In 1837, as a delegate to Pennsylvania’s constitutional convention, he had refused to sign the state’s new frame of government because it abrogated African Americans’ right to vote. During the Civil War, he was among the first to advocate the emancipation of the slaves and the enrollment of black soldiers. The most radical of the Radical Republicans, he even proposed confiscating the land of Confederate planters and distributing small farms to the former slaves.

On June 13, 1866, Thaddeus Stevens, the Republican floor leader in the House of Representatives and the nation’s most prominent Radical Republican, rose to address his Congressional colleagues on the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution. Born during George Washington’s administration, Stevens had enjoyed a career that embodied, as much as any other person’s, the struggle against slavery and for equal rights for black Americans. In 1837, as a delegate to Pennsylvania’s constitutional convention, he had refused to sign the state’s new frame of government because it abrogated African Americans’ right to vote. During the Civil War, he was among the first to advocate the emancipation of the slaves and the enrollment of black soldiers. The most radical of the Radical Republicans, he even proposed confiscating the land of Confederate planters and distributing small farms to the former slaves.

Like other Radical Republicans, Stevens believed that Reconstruction was a golden opportunity to purge the nation of the legacy of slavery and create a "perfect republic," whose citizens enjoyed equal civil and political rights, secured by a powerful and beneficent national government. In his speech on June 13 he offered an eloquent statement of his political dream—"that the intelligent, pure and just men of this Republic . . . would have so remodeled all our institutions as to have freed them from every vestige of human oppression, of inequality of rights, of the recognized degradation of the poor, and the superior caste of the rich." Stevens went on to say that the proposed amendment did not fully live up to this vision. But he offered his support. Why? "I answer, because I live among men and not among angels." A few moments later, the Fourteenth Amendment was approved by the House. It became part of the Constitution in 1868.

The Fourteenth Amendment did not fully satisfy the Radical Republicans. It did not abolish existing state governments in the South and made no mention of the right to vote for blacks. Indeed it allowed a state to deprive black men of the suffrage, so long as it suffered the penalty of a loss of representation in Congress proportionate to the black percentage of its population. (No similar penalty applied, however, when women were denied the right to vote, a provision that led many advocates of women’s rights to oppose ratification of this amendment.)

Nonetheless, the Fourteenth Amendment was the most important constitutional change in the nation’s history since the Bill of Rights. Its heart was the first section, which declared all persons born or naturalized in the United States (except Indians) to be both national and state citizens, and which prohibited the states from abridging their "privileges and immunities," depriving any person of life, liberty, or property without due process of law, or denying them "equal protection of the laws." In clothing with constitutional authority the principle of equality before the law regardless of race, enforced by the national government, this amendment permanently transformed the definition of American citizenship as well as relations between the federal government and the states, and between individual Americans and the nation. We live today in a legal and constitutional system shaped by the Fourteenth Amendment.

The Fourteenth Amendment was one of three changes that altered the Constitution during the Civil War and Reconstruction. The Thirteenth Amendment, ratified in 1865, irrevocably abolished slavery throughout the United States. The Fifteenth, which became part of the Constitution in 1870, prohibited the states from depriving any person of the right to vote because of race (although leaving open other forms of disenfranchisement, including sex, property ownership, literacy, and payment of a poll tax). In between came the Reconstruction Act of 1867, which gave the vote to black men in the South and launched the short-lived period of Radical Reconstruction, during which, for the first time in American history, a genuine interracial democracy flourished. "Nothing in all history," wrote the abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, equaled "this . . . transformation of four million human beings from . . . the auction-block to the ballot-box."

These laws and amendments reflected the intersection of two products of the Civil War era—a newly empowered national state and the idea of a national citizenry enjoying equality before the law. These legal changes also arose from the militant demands for equal rights from the former slaves themselves. As soon as the Civil War ended, and in some places even before, blacks gathered in mass meetings, held conventions, and drafted petitions to the federal government, demanding the same civil and political rights as white Americans. Their mobilization (given moral authority by the service of 200,000 black men in the Union Army and Navy in the last two years of the war) helped to place the question of black citizenship on the national agenda.

The Reconstruction Amendments, and especially the Fourteenth, transformed the Constitution from a document primarily concerned with federal-state relations and the rights of property into a vehicle through which members of vulnerable minorities could stake a claim to substantive freedom and seek protection against misconduct by all levels of government. The rewriting of the Constitution promoted a sense of the document’s malleability, and suggested that the rights of individual citizens were intimately connected to federal power. The Bill of Rights had linked civil liberties and the autonomy of the states. Its language—"Congress shall make no law"—reflected the belief that concentrated power was a threat to freedom. Now, rather than a threat to liberty, the federal government, declared Charles Sumner, the abolitionist US senator from Massachusetts, had become "the custodian of freedom." The Reconstruction Amendments assumed that rights required political power to enforce them. They not only authorized the federal government to override state actions that deprived citizens of equality, but each ended with a clause empowering Congress to "enforce" them with "appropriate legislation." Limiting the privileges of citizenship to white men had long been intrinsic to the practice of American democracy. Only in an unparalleled crisis could these limits have been superseded, even temporarily, by the vision of an egalitarian republic embracing black Americans as well as white and presided over by the federal government.

Constitutional amendments are often seen as dry documents, of interest only to specialists in legal history. In fact, as the amendments of the Civil War era reveal, they can open a window onto broad issues of political and social history. The passage of these amendments reflected the immense changes American society experienced during its greatest crisis. The amendments reveal the intersection of political debates at the top of society and the struggles of African Americans to breathe substantive life into the freedom they acquired as a result of the Civil War. Their failings—especially the fact that they failed to extend to women the same rights of citizenship afforded black men—suggest the limits of change even at a time of revolutionary transformation.

Moreover, the history of these amendments underscores that rights, even when embedded in the Constitution, are not self-enforcing and cannot be taken for granted. Reconstruction proved fragile and short-lived. Traditional ideas of racism and localism reasserted themselves, Ku Klux Klan violence disrupted the Southern Republican party, and the North retreated from the ideal of equality. Increasingly, the Supreme Court reinterpreted the Fourteenth Amendment to eviscerate its promise of equal citizenship. By the turn of the century, the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments had become dead letters throughout the South. A new racial system had been put in place, resting on the disenfranchisement of black voters, segregation in every area of life, unequal education and job opportunities, and the threat of violent retribution against those who challenged the new order. The blatant violation of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments occurred with the acquiescence of the entire nation. Not until the 1950s and 1960s did a mass movement of black southerners and white supporters, coupled with a newly activist Supreme Court, reinvigorate the Reconstruction Amendments as pillars of racial justice.

Today, in continuing controversies over abortion rights, affirmative action, the rights of homosexuals, and many other issues, the interpretation of these amendments, especially the Fourteenth, remains a focus of judicial decision-making and political debate. We have not yet created the "perfect republic" of which Stevens dreamed. But more Americans enjoy more rights and freedoms than ever before in our history.

Eric Foner, the DeWitt Clinton Professor of History at Columbia University, is the author of numerous books on the Civil War and Reconstruction. His most recent book, The Fiery Trial: Abraham Lincoln and American Slavery (2010), has received the Pulitzer, Bancroft, and Lincoln Prizes.

Suggested Sources

Books and Printed Materials

A selection of relevant books by the author of this essay:

Foner, Eric. Forever Free: The Story of Emancipation and Reconstruction. New York: Knopf, 2005.

Foner, Eric. Nothing But Freedom: Emancipation and Its Legacy. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2007.

Foner, Eric. Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1807. New York: Perennial Classics, 2002.

On the adoption of the Reconstruction Amendments:

Maltz, Earl M. Civil Rights, the Constitution, and Congress, 1863–1869. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1990.

The Reconstruction Amendments’ Debates: The Legislative History and Contemporary Debates in Congress on the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments. Richmond: Commission on Constitutional Government, 1963.

Richards, David A. Conscience and the Constitution: History, Theory, and Law of the Reconstruction Amendments. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993.

On Thaddeus Stevens:

Stevens, Thaddeus. The Selected Papers of Thaddeus Stevens. Beverly Wilson Palmer and Holly Byers Ochoa, eds. 2 vols. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1997.

Internet Resources

Yale University’s "Avalon Project" for a multitude of documents related to American legal and constitutional history: http://avalon.law.yale.edu/default.asp

For images of manuscript copies of the amendments, transcripts of their texts, and brief background information, see the National Archives’ "Our Documents" site:

http://www.ourdocuments.gov/doc.php?doc=40 [Thirteenth Amendment]

http://www.ourdocuments.gov/doc.php?doc=43 [Fourteenth Amendment]

http://www.ourdocuments.gov/doc.php?doc=44 [Fifteenth Amendment]