Lincoln at Cooper Union

by Harold Holzer

In March 1860, just a few weeks after returning home from his triumphant visit to New York to deliver his Cooper Union address, Lincoln went on the road yet again. He traveled up from Springfield, Illinois, to Chicago to complete important legal work for the Illinois Central Railroad. While he was in Chicago, he agreed to sit for a wet-plaster life mask at the studio of the sculptor Leonard Wells Volk. While Volk prepared his materials for the mask, he and Lincoln chatted. Twenty years later, Volk published his recollections of that conversation, revealing that Lincoln had admitted to having "arranged and composed" his famous Cooper Union address "in his mind while going on the cars from Camden to Jersey City."

In March 1860, just a few weeks after returning home from his triumphant visit to New York to deliver his Cooper Union address, Lincoln went on the road yet again. He traveled up from Springfield, Illinois, to Chicago to complete important legal work for the Illinois Central Railroad. While he was in Chicago, he agreed to sit for a wet-plaster life mask at the studio of the sculptor Leonard Wells Volk. While Volk prepared his materials for the mask, he and Lincoln chatted. Twenty years later, Volk published his recollections of that conversation, revealing that Lincoln had admitted to having "arranged and composed" his famous Cooper Union address "in his mind while going on the cars from Camden to Jersey City."

Volk was only one of the many people who had known the assassinated president and who had been part of Lincoln’s ready audience for presumably reliable first-hand stories. Indeed, by then, Lincoln’s myth-worthy creative ability had emerged as a crucial element of his reigning image.

Volk’s recollection about Cooper Union seemed well in keeping with the hagiography of the day. A president who allegedly had been able to create his greatest masterpiece on the back of an envelope while riding on a train to Gettysburg surely could have written his Cooper Union address on a train to New York—even in the few hours it took to ride only from Camden to Jersey City near the end of his long journey from Springfield.

Of course, like the Gettysburg legend, the Cooper Union story was entirely false. That could have been because Volk’s recollection was cloudy. But Lincoln should not be automatically exonerated from the small crime of promulgating this version of how the speech was written. He may have dealt with Volk’s compliment on this speech by protesting, modestly declaring he had dashed it off at the last minute.

In any event, Volk’s story was particularly ironic, for Lincoln had never labored over an address as diligently, and over such an extended period of time, as he did in preparing his Cooper Union speech. Writing eight years after Volk, Lincoln’s longtime law partner, William H. Herndon, set the record straight. From Herndon, we know that Lincoln devoted an enormous amount of time between his acceptance and his departure for New York to "careful preparation" of his lecture. As Herndon remembered it, "He searched through the dusty volumes of congressional proceedings in the State library, and dug deeply into political history. He was painstaking and thorough in the study of his subject."

But lack of preparation—or, to put a more positive spin on the fable, divine last-minute inspiration—was not the only myth that arose out of Lincoln’s Cooper Union speech. Another was that the school’s cavernous, gas-lit Great Hall was overflowing with people on the memorable February night of Lincoln’s appearance. This was what the more enthusiastic newspapers reported.

In truth, as many as a fourth of the hall’s 1,800 plush seats remained empty for the much touted political lecture. On that Monday, February 27, just as now, New Yorkers could choose their "amusements" from a wide menu of activities. Only a few blocks from Cooper Union, at the Academy of Music, a sensational sixteen-year-old soprano from Italy was set to make her debut in the opera Martha. Music lovers who preferred established stars could hear the legendary "Swedish Nightingale," Jenny Lind, at the Winter Garden.

For more prosaic tastes, the Palace Garden advertised the largest menagerie of elephants, pumas, hyenas, zebras, and vultures in the world. And warning that "the last week of the equestrian season" was at hand, Cooke’s Royal Amphitheatre offered a troupe of performing ponies and "educated" horses. Niblo’s Saloon Christy’s Minstrels, specializing in songs and farce, were performing in blackface. And over at Barnum’s Museum, five acts of tableaux vivant were set to unfold in "that surpassingly popular, touching, amusing, and beautiful picture of Southern life, Octoroon, or Life in Louisiana." As a bonus, Barnum’s irresistible sideshow featured, as its latest resident, a pathetic, physically deformed African American child billed as a "unique specimen of Brute Humanity" from the Congo, "half negro and half orang-outang." How was the discriminating New Yorker to choose among such riches?

Nor was Cooper Union the only hall in town presenting a lecturer that evening. Over at Goldbeck’s Music Hall, one J. H. Siddons was scheduled to enthrall husbands and wives alike with a talk on "the Great Domestic Obligation." The nearby Inebriate’s Home offered a temperance lecture. For self-help devotees, the Reverend Theodore Culyer would ascend the podium at the YMCA to orate on "The Intellect and How to Use It." And a medical doctor was to launch a series of lectures on the lungs and digestive organs.

Serious drama was also there to tempt New Yorkers. For a mere fifty cents, they could enjoy famous English actress Laura Keene in the popular play "Jeannie Deans," which had already attracted 109,000 spectators. Not one of them, of course, could possibly have known that just five years later, Miss Keene would be appearing on stage in a different play at Ford’s Theatre in Washington at the very moment an assassin’s bullet would end Lincoln’s life.

As for the speech venue itself, political lectures at Cooper Union had become all but routine over the past few months. Two weeks earlier, the anti-slavery leader from Kentucky, Cassius Marcellus Clay, had spoken on "the progress and principles of Republicanism." Missouri politician Frank Blair had appeared recently, too, to deliver another of these "pay political lectures." Any orator following such luminaries onto the Cooper Union stage faced a daunting challenge. To imagine that Lincoln would have left it to chance and risked delivering an impromptu speech is not only a myth, but a historical improbability.

That Lincoln triumphed against such competition—attracting a sizeable audience, including the "pick and flower of New York culture," along with an army of journalists eager to record and reprint his words—was a tribute not only to his political prescience but also to his inexhaustible constitution. Not only had he researched and written by hand a 7,500-word speech in the midst of much diversionary legal and political business, he also had endured a tiring cross-country train journey to deliver it. Yet for some reason, history remains littered with misconceptions about the speech, perhaps as an excuse to ignore its dauntingly lengthy contents.

A final legend involved the notorious New York weather. February had been a miserable month in the city. So much snow had accumulated that sewers had clogged, leaving streets awash in mud and muck, and triggering fears about diphtheria, rheumatism, chills, "and other bodily evils." A violent rainstorm on Washington’s Birthday, the 22nd, disrupted traffic and tortured holiday marchers. Then a dense fog rolled in, bringing traffic to an eerie halt on both land and rivers. Within hours, May-like breezes billowed into town, turning the city’s streets into an "ice-cream mixture" of "mud" and "splosh."

Some eyewitnesses, and generations of historians, would report another snowstorm the night Lincoln spoke. ("The profits were so small . . . because the night was so stormy," recalled a co-organizer). Perhaps contemporary Lincoln supporters said so to help explain the hundreds of empty seats. But long-unknown meteorological records attest to the fact that the weather was clear and unseasonably warm on the day of Lincoln’s speech. If anything, the Great Hall must have been a hot, humid furnace that evening—boilers raging despite fifty-degree temperatures, further testing the orator.

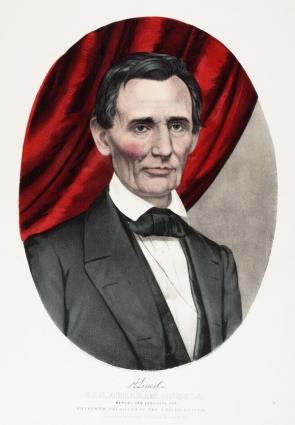

Standing before the crowd that night was an ungainly giant, at six feet, four inches dwarfing the other dignitaries on the stage, clad in a wrinkled black suit that ballooned out in the back. "At first sight there was nothing impressive or imposing about him," recalled one eyewitness. The speaker appeared decidedly "ill at ease." Yet the power of his words and the earnestness of his delivery quickly converted doubters in the crowd, at the high watermark of a vanished era in which one major speech could make or break a rising leader. When Lincoln finished his carefully prepared address, the audience rose and cheered wildly. Abraham Lincoln came to New York an untested presidential aspirant. He left a potential White House nominee.

Then, as now—as long as the star attraction is gifted and well prepared—if you can make it there, you can make it anywhere.

Harold Holzer is senior vice president for external affairs at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and chairman of the Lincoln Bicentennial Foundation. Author of many books on Abraham Lincoln, he received the Lincoln Prize in 2015 for Lincoln and the Power of the Press: The War for Public Opinion (2014).