African American Religious Leadership and the Civil Rights Movement

by Clarence Taylor

Clarence Taylor is Professor Emeritus of Modern African American History, Religion, and Civil Rights at Baruch College, The City University of New York. His books include The Black Churches of Brooklyn (1994), Knocking at Our Own Door: Milton A. Galamison and the Struggle to Integrate New York City Schools (1997), Black Religious Intellectuals: The Fight for Equality from Jim Crow to the 21st Century (2002), and Reds at the Blackboard: Communism, Civil Rights, and the New York City Teachers Union (2011). He is co-editor, with Jonathan Birnbaum, of the prizewinning collection Civil Rights Since 1787: A Reader in the Black Struggle (New York University Press, 2000).

The modern Civil Rights Movement was the most important social protest movement of the twentieth century. People who were locked out of the formal political process due to racial barriers were able to mount numerous campaigns over three decades to eradicate racial injustice and in the process transform the nation. In its greatest accomplishment, the Civil Rights Movement successfully eliminated the American apartheid system popularly known as Jim Crow.

The modern Civil Rights Movement was the most important social protest movement of the twentieth century. People who were locked out of the formal political process due to racial barriers were able to mount numerous campaigns over three decades to eradicate racial injustice and in the process transform the nation. In its greatest accomplishment, the Civil Rights Movement successfully eliminated the American apartheid system popularly known as Jim Crow.

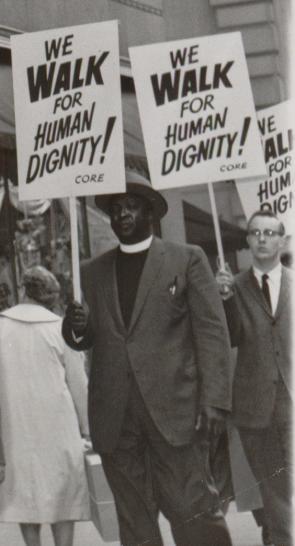

A major reason for the movement’s success was its religious leadership. The Reverends Martin Luther King Jr., Andrew Young, Fred Shuttlesworth, Wyatt T. Walker, Joseph Lowery, and Jesse Jackson were just a few of the gifted religious figures who played a national leadership role in the movement. In many instances black clergy became the spokespeople for campaigns articulating the grievances of black people, and they became the strategists who shaped the objectives and methods of the movement that sought to redress those grievances. Furthermore, they were able to win the allegiance of a large number of people and convince them to make great sacrifices for racial justice.

One trait that helped black ministers win support was their charismatic style of oratory, which was used both to convey meaning and to inspire people involved in the struggle for racial equality. The rhetoric that the ministers used explained that the civil rights participants were engaged in a religious as well as an historical mission. Ministers spoke of the holy crusade to force America to live up to its promise of democracy. For example, in a 1963 campaign to force the state of New York and the building-trade unions to hire black and Hispanic construction workers at the Downstate Medical Center in Brooklyn, ministers involved in the struggle told their congregations that they were part of a "moral and patriotic movement" to make America more democratic. "There will be no turning back until people in high places correct the wrongs of the nation," the Reverend Gardner C. Taylor of Concord Baptist Church in Brooklyn declared in a speech to a crowd of 6,000. Ministers like Taylor were able to use a certain rapidity, tempo, and reiteration in their sermons and speeches that evoked an emotional response from their audience. These performances convinced followers that their cause was right and that their pastors were called to a divine task by God. Many participants in the Birmingham, Alabama, bus boycott noted they became involved in the campaign because they were inspired by their charismatic pastors.

Beyond Ministerial Leadership

Ministers became the spokespeople that a predominantly white media presented as leaders of the movement. However the religious leadership of the Civil Rights Movement was not limited to these ministers but encompassed nonclerical church leaders, many of whom had still deeper roots in the black community than the ministers. Besides nurturing charismatic ministers, most of whom were men, black churches also helped instill cooperative values in nonclerical leaders, emphasizing democracy, equality, and caring for others. The process of cultivating cooperative values usually took place outside of conventional avenues of ministerial training such as seminaries, ministerial alliances, and denominational conventions, which emphasized a hierarchical approach to leadership. Instead, the institutions responsible for inculcating cooperative values in church members—clubs, choirs, missionary societies, and other church auxiliaries—were both created and operated by lay members of churches.

In church auxiliaries, most of which were created and run by women of the church, members learned to handle money, speak in public, and work on behalf of the less fortunate. Auxiliaries provided a space in which members socialized, developed strong bonds, and worked on tasks in a supportive atmosphere. Although the role of laity in the Civil Rights Movement is still an unwritten history, there is evidence that auxiliaries played a pivotal role in what happened. For instance, the laity of black churches organized the carpools used during the bus boycotts in Louisiana and Alabama. And in the North, the auxiliaries of Siloam Presbyterian Church in Brooklyn created a schedule designating a specific day that members of a particular auxiliary would participate in the protest at the Brooklyn construction site. Many of the church members from Siloam and other churches that participated became "jailbirds for freedom," volunteering to be arrested at the construction site. This willingness to make a sacrifice for the struggle was encouraged by the collective sentiment fostered in these church’s auxiliaries. Gwendolyn Timmons, a member of Siloam’s choir, recalls being arrested at Downstate because members of the choir had pledged to join the picket line. Most of the black women active in the Birmingham, Alabama, bus boycott belonged to Baptist churches and were members of those churches’ choirs, missionary societies, usher boards, pastor aid societies, and other auxiliaries. Although many asserted that they became involved in the movement because of their pastors’ leadership, others attributed their involvement to their belief in a religion that dedicated itself to addressing the social conditions of the oppressed.

The collective sentiment of helping the oppressed had been a longstanding objective of these lay religious organizations. Ella Baker, who became one of the movement’s key leaders and thinkers, recalled her mother’s involvement with the women’s missionary movement of black churches and how her mother embraced the missionary groups’ stress on communal support to black communities. This concern for oppressed communities would influence Baker’s thinking and political activity.

Perhaps the best-known leader in the Civil Rights Movement who expressed the cooperative values of the church was Fannie Lou Hamer. Born in poverty in rural Mississippi, Hamer finished only the sixth grade and picked cotton to survive in the Jim Crow South. She was deeply religious, and the Baptist church that she attended, where she read and studied the Bible, was a central part of her life. Hamer’s religious convictions informed her politics. After she joined SNCC, she dedicated herself to improving the lives of black families. Bob Moses, head of the Mississippi Freedom Summer Campaign, noted that Hamer sang the spirituals that she had learned in the church at civil rights gatherings to help foster a feeling of community among the young SNCC activists.

Hamer became field secretary for SNCC and a founding member of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP), and she ran for Congress. She helped lead the voter registration campaign in Mississippi, and was arrested and beaten for her activity. As a leader of the MFDP, which challenged the all-white Mississippi delegation to the Democratic National Convention in 1964, Hamer addressed the nation. She spoke of her own plight, the murder of civil rights activists, and the racial terror that black Mississippians faced for attempting to exercise their rights. She questioned the nation’s commitment to democracy if the Democratic convention failed to unseat the all-white delegation from Mississippi and recognize delegates from the MFDP. When the Democratic Party’s leadership, with the support of prominent civil rights leaders, worked out a compromise to give two seats to members of the MFDP, the dissident group of delegates rejected the deal because all of the members would not be seated. It was Hamer who best expressed the cooperative spirit of black religious institutions when she said, "We didn’t come for no two seats when all of us is tired."

It was through a coordinated effort between the clerical and nonclerical leadership at the national and local levels that victories were achieved. It is important to pay attention to the contributions that individual religious leaders made to the Civil Rights Movement. However, to more fully understand the role black churches played in the movement, it is equally important to examine the cooperative values that these churches fostered in leaders outside of the clergy. Some people say we need another Martin Luther King. What is needed is an army of Fannie Lou Hamers.

Suggested Sources

Books and Printed Materials

For background on the role of African American religious leaders as political activists throughout American history, one by the author of this essay:

Swift, David Everett. Black Prophets of Justice: Activist Clergy before the Civil War. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1989.

Taylor, Clarence. Black Religious Intellectuals: The Fight for Equality from Jim Crow to the Twenty-First Century. New York: Routledge, 2002.

Biographies and autobiographies of individual clergy in the Civil Rights Movement:

Frady, Marshall. Jesse: The Life and Pilgrimage of Jesse Jackson. New York: Random House, 1996.

Gardner, Carl. Andrew Young: A Biography. New York: Drake, 1978.

Manis, Andrew Michael. A Fire You Can’t Put Out: The Civil Rights Life of Birmingham’s Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1999.

Young, Andrew. An Easy Burden: The Civil Rights Movement and the Transformation of America. New York: HarperCollins, 1996.

Books and videos on the lives of two of the women Dr. Taylor highlights as examples of the laywomen who spearheaded the Civil Rights Movement in their churches and communities:

Fannie Lou Hamer: Everyday Battle. Atlanta, GA: History on Video, Inc., 1999.

Fundi: The Story of Ella Baker. New York: Fundi Productions; distributed by First Run, 1986.

Lee, Chana Kai. For Freedom’s Sake: The Life of Fannie Lou Hamer. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1999.

Mills, Kay. This Little Light of Mine: The Life of Fannie Lou Hamer. New York: Dutton, 1993.

Ransby, Barbara. Ella Baker and the Black Freedom Movement: A Radical Democratic Vision. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003.