"The Strange Spell That Dwells in Dead Men’s Eyes": The Civil War, by Brady

by Harold Holzer

"[T]he dead of the battle-field come up to us very rarely, even in dreams." So admitted the New York Times just a month after it had reported the grisly slaughter of 3,650 Union and Confederate troops at the Battle of Antietam. On a single afternoon of hideous carnage there, more soldiers had died than at any other place, or on any other day, in American history. Yet as vividly as battlefield correspondents described the carnage, home-front readers still seemed unable to visualize the magnitude of the tragedy—or the depth of individual human sacrifice it entailed. Words seemed insufficient. "We recognize the battle-field as a reality," the Times conceded, "but it stands as a remote one. It is like a funeral next door."

"[T]he dead of the battle-field come up to us very rarely, even in dreams." So admitted the New York Times just a month after it had reported the grisly slaughter of 3,650 Union and Confederate troops at the Battle of Antietam. On a single afternoon of hideous carnage there, more soldiers had died than at any other place, or on any other day, in American history. Yet as vividly as battlefield correspondents described the carnage, home-front readers still seemed unable to visualize the magnitude of the tragedy—or the depth of individual human sacrifice it entailed. Words seemed insufficient. "We recognize the battle-field as a reality," the Times conceded, "but it stands as a remote one. It is like a funeral next door."

"The funeral" came home soon enough. In October 1862, Mathew Brady—photographer, entrepreneur, celebrity, and showman—daringly placed on public exhibition in New York the images taken on the Antietam battlefield by his staff photographer, Alexander Gardner. No photographs of the actual fighting were among them. Such "news" images remained beyond the technological capacity of the infant medium. Rather, here were bloated bodies and gruesome burial pits, images captured once the fighting had ceased. Such limitations mattered not at all. The exhibit, titled "The Dead of Antietam," struck like a thunderbolt.

"Mr. Brady has done something to bring home to us the terrible reality and earnestness of the war," raved the Times. "If he has not brought bodies and laid them in our dooryards and along the streets, he has done something very like it. . . . You will see hushed, reverent groups standing around these weird copies of carnage, bending down to look in the pale faces of the dead, chained by the strange spell that dwells in dead men’s eyes." In a single display inside a darkened, second-floor Broadway gallery, the manner in which we see and understand war changed forever.

"Mr. Brady has done something to bring home to us the terrible reality and earnestness of the war," raved the Times. "If he has not brought bodies and laid them in our dooryards and along the streets, he has done something very like it. . . . You will see hushed, reverent groups standing around these weird copies of carnage, bending down to look in the pale faces of the dead, chained by the strange spell that dwells in dead men’s eyes." In a single display inside a darkened, second-floor Broadway gallery, the manner in which we see and understand war changed forever.

Hundreds of photographers, Northern as well as Southern, had headed off to cover the war. But no two picture-makers made as enormous an impression—in their own time and since—as did Mathew Brady and Alexander Gardner.

Brady came virtually to symbolize Civil War photography—deservedly, in a way, and unjustly, in another. Born in 1822 in Ireland (a fact he later tried to conceal by claiming his birthplace to be upstate New York), Mathew Brady became America’s most distinguished photographer years before he was thirty. A brilliant portraitist, he brought out the best in several generations of prominent Americans, among them politicians, military heroes, tycoons, writers, actors, even circus performers. His Manhattan galleries flourished, becoming tourist attractions in their own right. Brady routinely rushed his photographs to nearby printmakers and publishers, who copied and reproduced them within days in Harper’s Weekly or Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper. Brady accumulated medals, fame, and fortune. He had no peer.

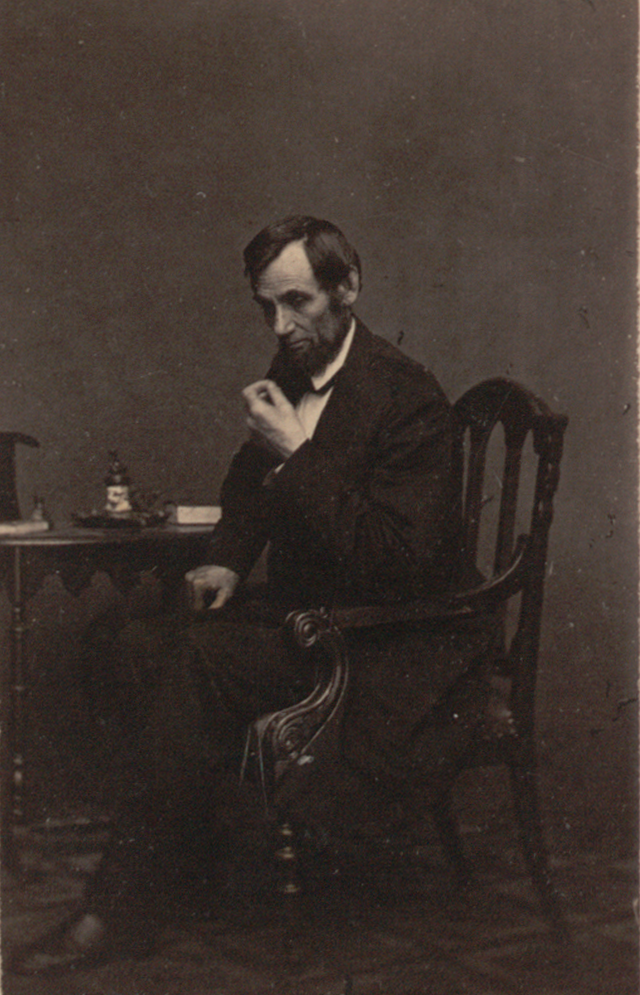

In February 1860, a group of Republican activists brought yet another sitter to Brady’s: a tall Illinois visitor named Abraham Lincoln, scheduled to speak that same evening at Cooper Union. The resulting photograph helped transform the prairie orator into a national celebrity. "I suppose they got my shaddow," Lincoln drawled a few months after his visit, "and can multiply copies indefinitely." That may have been the understatement of the year. During the 1860 race for the White House, Lincoln followed tradition and did no campaigning of his own. Brady’s photograph—copied for posters, prints, broadsides, banners, and buttons—appeared in his place. Brady and the Cooper Union speech, Lincoln later admitted, "made me president." By year’s end, the introduction of glass-plate negatives made it possible for Brady and other photographers to reproduce their own prints in bulk. Photography, for fifteen years a medium designed to create one-of-a-kind souvenirs for sitters, or models for other artists, became the most popular, accessible, and endlessly reproducible visual phenomenon in the world.

In February 1860, a group of Republican activists brought yet another sitter to Brady’s: a tall Illinois visitor named Abraham Lincoln, scheduled to speak that same evening at Cooper Union. The resulting photograph helped transform the prairie orator into a national celebrity. "I suppose they got my shaddow," Lincoln drawled a few months after his visit, "and can multiply copies indefinitely." That may have been the understatement of the year. During the 1860 race for the White House, Lincoln followed tradition and did no campaigning of his own. Brady’s photograph—copied for posters, prints, broadsides, banners, and buttons—appeared in his place. Brady and the Cooper Union speech, Lincoln later admitted, "made me president." By year’s end, the introduction of glass-plate negatives made it possible for Brady and other photographers to reproduce their own prints in bulk. Photography, for fifteen years a medium designed to create one-of-a-kind souvenirs for sitters, or models for other artists, became the most popular, accessible, and endlessly reproducible visual phenomenon in the world.

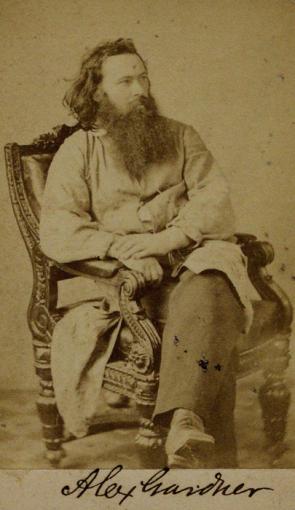

By the time Lincoln took office, a thriving Brady had opened an additional gallery in Washington, and was spending most of his time there. When secession unleashed war, public officials and military leaders alike flocked to the new studio to have their portraits made. One of Brady’s camera operators, a thickly bearded Scotsman named Alexander Gardner, a few months older than his employer but decidedly his professional junior, observed and absorbed his boss’s genius for posing his sitters.  As Brady’s delicate eyesight began to decline, Gardner gradually took on more and more of the camerawork. By the beginning of the war, it is probable that Brady himself could no longer focus a camera.

As Brady’s delicate eyesight began to decline, Gardner gradually took on more and more of the camerawork. By the beginning of the war, it is probable that Brady himself could no longer focus a camera.

Nonetheless, Brady decided to sideline his lucrative portrait practice and take his cameras—and assistants—to the front. Among Gardner’s friends was army espionage chief and fellow Scotsman Allan Pinkerton, who likely arranged passes to the front for the enterprise. Gardner (and other camera operators) rode Brady’s horse-drawn darkroom wagons to expose the actual pictures. But no one at the time doubted who ran the enterprise or owned the copyrights. Brady’s name adorned the wagons and appeared in bold script below or behind each published image. To cement his brand, Brady often posed in the background himself—easily identifiable, his pointy goatee invariably silhouetted in bold profile. Gardner and the others remained mere employees—at least as far as Brady was concerned. When the Antietam exhibition opened in New York City, Brady was identified as the creator of all the images.

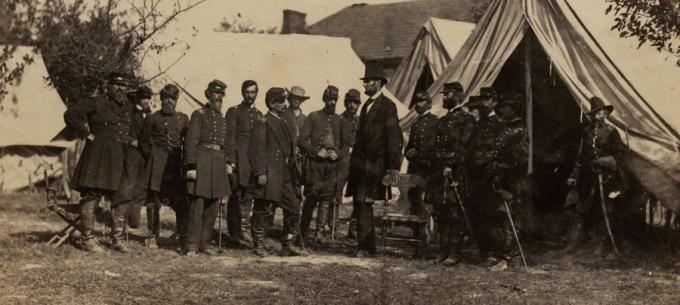

Bristling, Alexander Gardner decided to go independent. Launching his own studio in Washington, he scored President Abraham Lincoln as his very first sitter. Gardner had photographed Lincoln as President-elect a few days before the 1861 inaugural, and again in October 1862 at an outdoor conference with General George B. McClellan near Antietam—these, the very first portraits of an American commander in chief on a battlefield of war.

Bristling, Alexander Gardner decided to go independent. Launching his own studio in Washington, he scored President Abraham Lincoln as his very first sitter. Gardner had photographed Lincoln as President-elect a few days before the 1861 inaugural, and again in October 1862 at an outdoor conference with General George B. McClellan near Antietam—these, the very first portraits of an American commander in chief on a battlefield of war.

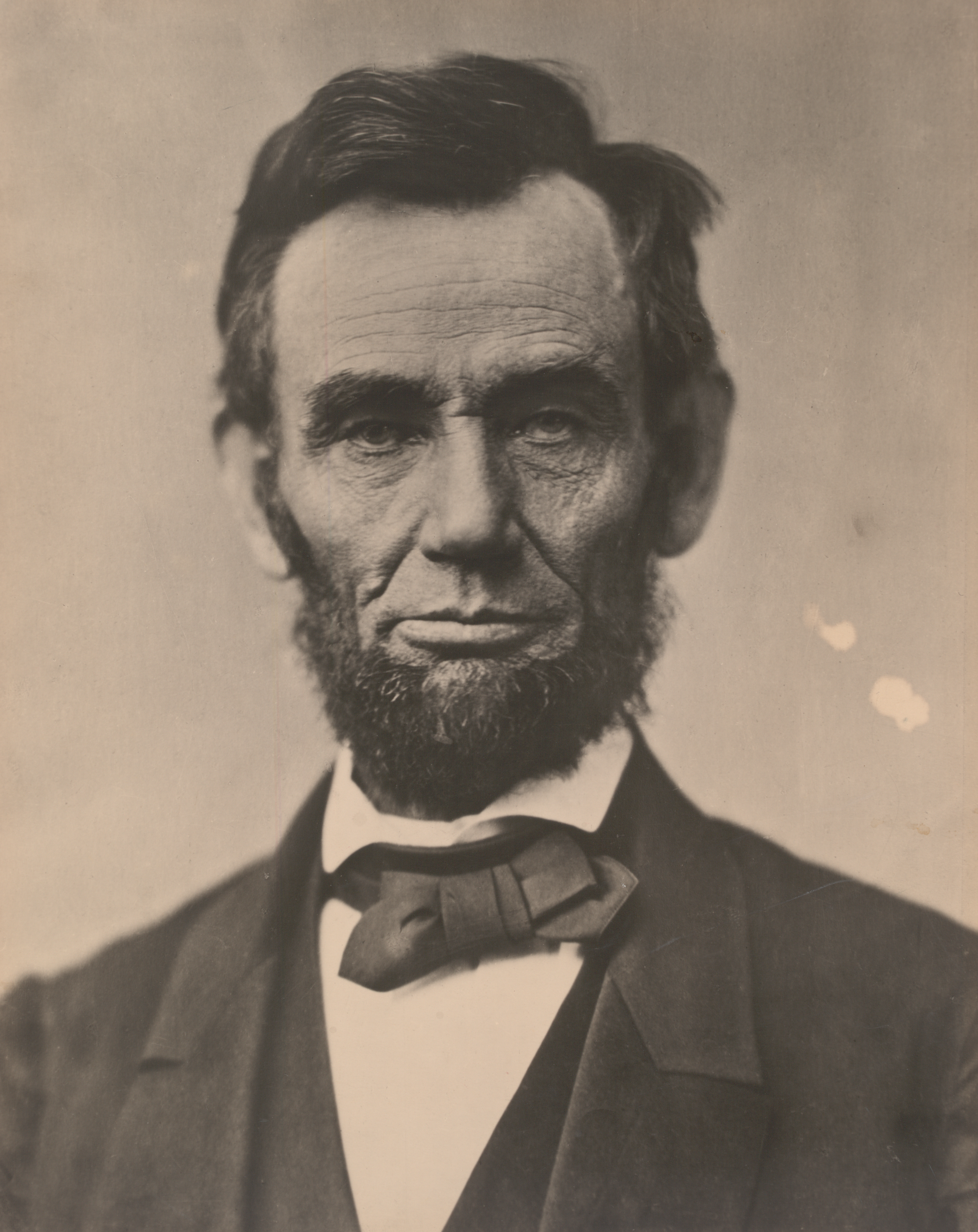

But those images, like all of Gardner’s wartime work to this point, had been credited to Brady. On Sunday, August 9, 1863, "in very good spirits," Lincoln sat for a series of pictures at Gardner’s own studio. Lincoln praised the unimpressive results, and Gardner made and sold countless copies. A few months later, just before heading off to Gettysburg to deliver "a few appropriate remarks" at its new soldiers’ cemetery, Lincoln returned, posing for one of the greatest sittings of his presidency. Back in August, Gardner may have told the president about his own visit to Gettysburg, where again he photographed rotting corpses just after the fighting ceased. This time, historians later alleged, the photographer may have moved and arranged dead bodies in order to make his compositions more dramatic. True or not, the results evoked the same response as the pictures he had taken the previous year at Antietam.

Between his own well-publicized visits to the front, Mathew Brady continued to preside over his Pennsylvania Avenue gallery, to which Lincoln returned in February 1864 for yet another great sitting—the actual portraits this time posed by artist Francis B. Carpenter and taken by Brady’s new camera operator, Thomas Le Mere. In Gardner’s absence, Timothy O’Sullivan and George N. Barnard were deployed to the field, creating additional series of "Brady" photographs right up to the capture of Richmond in 1865.

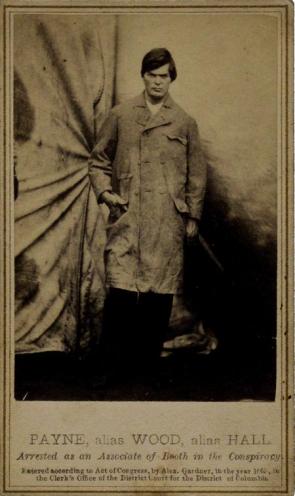

Gardner went on to take the very last studio photographs of an emaciated but happy Lincoln in February 1865. Five months later, he secured permission to take the only photographs of the execution of the Lincoln assassination conspirators. Eventually, Gardner published his own work in a Photographic Sketch Book of the Civil War. A rarity today, it made the photographer little money at the time, though Gardner later earned official government work in the West. He died in 1882. As for Brady, all but ruined by the war, he tried repeatedly to sell his 10,000 glass negatives to the government. He won but one $25,000 grant, which represented only a fourth of the investment he had poured into photographing the war. Bankrupt, Brady died in a hospital charity ward in 1896—so blind that he likely did not see the streetcar that had fatally struck him down on a New York street.

Gardner went on to take the very last studio photographs of an emaciated but happy Lincoln in February 1865. Five months later, he secured permission to take the only photographs of the execution of the Lincoln assassination conspirators. Eventually, Gardner published his own work in a Photographic Sketch Book of the Civil War. A rarity today, it made the photographer little money at the time, though Gardner later earned official government work in the West. He died in 1882. As for Brady, all but ruined by the war, he tried repeatedly to sell his 10,000 glass negatives to the government. He won but one $25,000 grant, which represented only a fourth of the investment he had poured into photographing the war. Bankrupt, Brady died in a hospital charity ward in 1896—so blind that he likely did not see the streetcar that had fatally struck him down on a New York street.

Whoever deserves principal credit for the thousands of pictures these two brave and innovative artists created—at such personal and financial peril—their extraordinary work stands today as the definitive pictorial archive of the American Civil War. Their gripping portraits of commanders, politicians, common soldiers, battlefield vistas, and of course, the dead and wounded, have focused our attention on the Civil War for a century and a half. No book on Antietam, Fredericksburg, or Gettysburg can be published without their photographs as illustrations; no biography of Lincoln can appear absent their portraits.

Above all, Brady and Gardner dared to make and exhibit those rows of gruesome casualties, staring back at generations of appropriately horrified viewers from hollow eyes inside swollen faces. They remind even the most jingoistic armchair generals of the unavoidable horrors of warfare. It took photography to touch this nerve, and gifted pioneers like Brady and Gardner to reach the highest levels of artistry.

"It seems somewhat singular," wrote the New York Times after that first "Brady" exhibition of the Antietam dead, "that the same sun that looked down on the faces of the slain, blistering them, blotting out from the bodies all semblance to humanity, and hastening corruption, should have thus caught their features . . . and given them perpetuity for ever. But so it is."

Harold Holzer has written extensively on Abraham Lincoln and the Civil War. His book Lincoln and the Power of the Press: The War for Public Opinion (Simon & Schuster, 2014) was awarded the 2015 Gilder Lehrman Lincoln Prize. His many other publications include Lincoln President-Elect: Abraham Lincoln and the Great Secession Winter 1860–1861 (Simon & Schuster, 2008) and Lincoln at Cooper Union: The Speech That Made Abraham Lincoln President (Simon & Schuster, 2004).