The Relevance of Gettysburg

by D. Scott Hartwig

Joshua Chamberlain, who earned a Medal of Honor for his leadership and the courageous stand of his regiment, the 20th Maine, on Little Round Top on July 2, 1863, during the Battle of Gettysburg, reflected after the war that, "generations that know us not and that we know not of, heart-drawn to see where and by whom great things were suffered and done for them, shall come to this deathless field, to ponder and dream."[1]

Joshua Chamberlain, who earned a Medal of Honor for his leadership and the courageous stand of his regiment, the 20th Maine, on Little Round Top on July 2, 1863, during the Battle of Gettysburg, reflected after the war that, "generations that know us not and that we know not of, heart-drawn to see where and by whom great things were suffered and done for them, shall come to this deathless field, to ponder and dream."[1]

Chamberlain was right. Generations that did not know him or any of the others who made history at Gettysburg continue to come to Gettysburg. This year, the 150th anniversary of the battle, nearly 250,000 people visited the National Military Park over a ten-day period that included the battle’s anniversary.

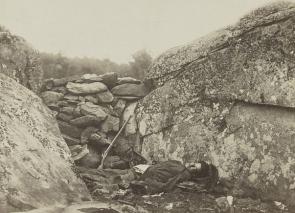

In a typical year some 1.5 million will visit the park. They come for a variety reasons. Curiosity draws many. Others had ancestors who served. But perhaps more than anything, visitors continue to come to Gettysburg because it continues to have and reveal real meaning. It was and is more than just a terrible, bloody battle. The battle and the war it was a part of shaped our nation and helped define us as a people. But Gettysburg is more than that, too. It offers us lessons in courage, fortitude, grief, death, suffering, leadership, character, and resiliency that, as Chamberlain understood, remain timeless.

What Gettysburg means to us and continues to teach us is particularly relevant to young people, who retain the most knowledge when the learning is experiential. Gettysburg offers a unique classroom for students. The 1863 landscape is extremely well preserved and it is possible to walk in the footsteps of the great leaders, but also of sergeants and privates and farmers, and young women who found themselves assisting in field hospitals and doing and seeing things they had never imagined. The two men who commanded the opposing armies and made history at Gettysburg—George G. Meade, commander of the Union Army of the Potomac, and Robert E. Lee, commander of the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia—offer excellent examples for students to put themselves in the shoes of people from the past who faced tremendous challenges. It is one thing to read about these people; it is another to stand in their footsteps where they made history. This is when history becomes real and accessible rather than abstract.

Few visitors to Gettysburg National Military Park have ever heard of George G. Meade. During their visit they learn that he commanded the Union Army of the Potomac during the battle. But he remains a relative unknown in our history. Yet Meade provides a wonderful case study of a leader thrust into a remarkably difficult and challenging position, something many of us will encounter in our lives, although hopefully on a far lesser scale than Meade. On June 28, 1863, Meade was still the commander of the Union Army of the Potomac’s 5th Corps, an organization of about 10,000 men. But that day the army commander, Major General Joseph Hooker, resigned, and President Lincoln ordered that Meade be named commander of the 90,000-man army. What no one knew was that in three days Meade and his army would be in a death struggle with the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia at Gettysburg. Few military leaders, if any, in our nation’s history have been placed in the position Meade found himself in. When he wrote his wife to tell her that he was now the army commander he asked her to pray for him and to pray for their country, for the fate of it rested upon the outcome of the upcoming battle.

Although it is important not to grant Gettysburg undue importance in a sprawling four-year war, Meade was not far from the mark. The bottom line was that Meade could not lose the battle. The Northern public were growing weary of the war, and a peace movement that would have granted Southern independence was growing, fueled in large part by two major defeats to the Army of the Potomac, at Fredericksburg in December 1862 and Chancellorsville in May 1863. Lee and his Army of Northern Virginia appeared invincible, and now, in the summer of 1863, they had marched across northern Virginia, down the Shenandoah Valley, across the Potomac River into Maryland and entered Pennsylvania with impunity.

Although the governor of Pennsylvania called out the militia, it proved nothing more than a nuisance to the Confederates, who quickly and easily occupied all the major towns in the south-central part of the state—Chambersburg, Carlisle, and York—and part of the army was maneuvering against the state capital at Harrisburg. Lee’s strategy was sound—convince the Northern people that a continued war was both useless and senseless by proving that his army could march at will into the North and defeat anything the United States might send against it. To drive this point home Lee needed to draw the Union Army of the Potomac into Pennsylvania and defeat it on northern soil. He sought a showdown battle that would fuel the peace movement and bring a negotiated end to the war, which meant Confederate victory, an end to the United States as it had been in 1860, and the existence of a new powerful slave-holding republic in North America.

The Battle Begins

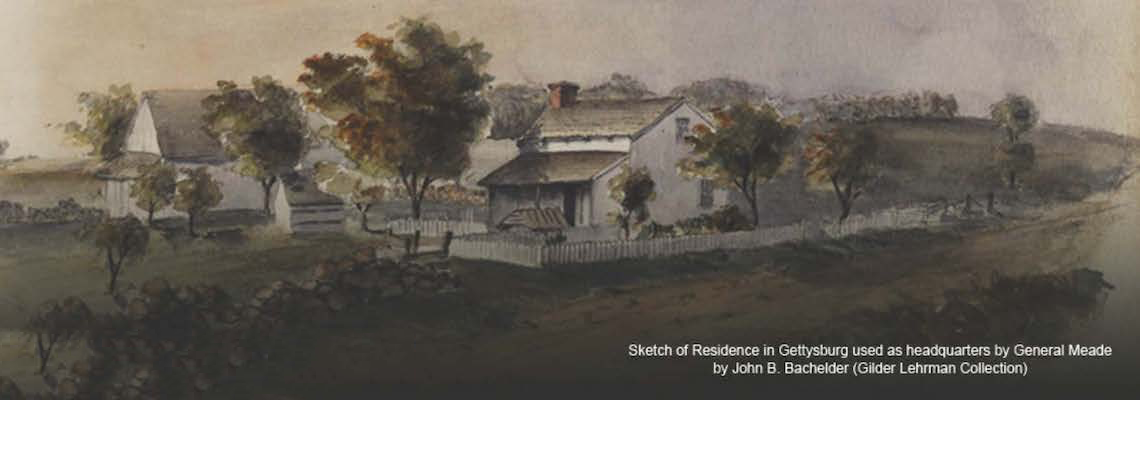

The Lydia Leister house is a small white farmhouse and barn that sits astride the Taneytown Road and is only a ten-minute walk from the park visitor center. Here, it is possible to stand in George Meade’s footsteps and sense something of the loneliness and the challenge of command. This was his headquarters during the battle. Meade did not pick the battlefield at Gettysburg. He had hoped to draw Lee onto a battlefield in northern Maryland that Meade had selected. It was a subordinate commander, Major General John Reynolds, to whom Meade had delegated considerable authority, who initiated the combat west of Gettysburg on the morning of July 1. Meade understood that leaders cannot control everything and that flexibility is crucial. He needed the latter quality, for the escalating battle at Gettysburg forced him to scrap his plans and order the army to march there. When he made this decision he was in Taneytown, Maryland, thirteen miles from the battlefield. He had never seen the field and knew nothing of the terrain. When a commander of 90,000 men makes a decision to move all his forces to a single point it is a decision not easily undone, particularly in an era when soldiers moved by foot or horse.

Meade arrived on the battlefield around midnight. He joined several of his commanders on Cemetery Hill where they advised him that, although they had been defeated that day and suffered heavy losses, they occupied a strong position. Meade responded that he was glad to hear it because it was too late to order the army anywhere else. The showdown battle with Lee and his army was to be at Gettysburg.

Sometime in the early morning Meade and his headquarters staff arrived at the Leister farm, and it became army headquarters. Standing outside the front door of Lydia Leister’s tiny frame house one can appreciate how little of the battlefield Meade could see. His front lines extended over nearly three miles. The headquarters had been established here not for the view but because it was sheltered from enemy observation and an equal distance from nearly any point on the army’s front. To manage his army and fight the battle Meade had communications that were no better than that available to Alexander the Great. He could send and receive written messages by courier, he could give verbal orders, and he could use signal flags for some communications. This meant that crucial decisions often had to be made on incomplete and sometimes inaccurate information. Meade also chose to fight a defensive battle, which meant that Lee had the initiative and could choose the time and place to attack.

Standing on the field today where Meade himself once stood gazing up toward Cemetery Ridge, one can ponder the enormous challenges he confronted. We can begin to feel something of the burden of uncertainty and anxiety that Meade had to overcome to make decisions and command effectively. "The most difficult part of my work is acting without correct information on which to predicate action," he wrote.[2] In the end, he rose to the challenge, guiding the Army of the Potomac to perhaps their most important victory of the war in the two days of fighting on July 2 and 3. But leadership and command come with a cost. Meade wrote his wife on July 8, "from the time I took command till to-day, now over ten days, I have not changed my clothes, have not had a regular night’s rest, and many nights not a wink of sleep, and for several days did not even wash my face and hands, no regular food, and all the time in a great state of mental anxiety. Indeed, I think I have lived as much in this time as in the last thirty years."[3]

A short walk up Cemetery Ridge from Meade’s headquarters brings you to the equestrian statue of George G. Meade. Meade gazes west across the open fields to the Virginia Memorial on Seminary Ridge. Atop it stands an equestrian statue of Robert E. Lee, mounted on his favorite horse, Traveler. Lee’s gaze is fixed upon the fields over which his army made the ill-fated attack on July 3, known today as Pickett’s Charge. The attack was a debacle, costing more than 1,000 Confederate soldiers their lives, with more than 4,500 others wounded or captured. It also cost Lee the battle, forced him to order a retreat to Virginia, and ended his invasion of Pennsylvania. For an aggressive, prideful man, defeat was a bitter pill to swallow. Lee is frequently considered a brilliant military commander who achieved numerous victories against great odds. But how he confronted defeat at Gettysburg is more instructive to young people than how he achieved his many victories.

Pickett’s Charge

Pickett’s Charge was a great gamble. After a massive artillery bombardment Lee planned to send some 13,000 infantry across a mile of open fields to carry the Union line on Cemetery Ridge. The most frequent comment from visitors who view this ground is "What was Lee thinking?" Lee was a carefully calculating general, and by the morning of July 3 all the information he was receiving indicated that the Union army was battered and that a powerful blow would deliver victory to his army. He also understood that the hopes of many in the Confederacy were riding upon the shoulders of his army. With diminishing resources and manpower, the Confederates needed a battlefield victory that would decisively shift the balance in the war. He sensed the opportunity before him might never present itself again. The army he commanded was a magnificent weapon of war. He believed his men could accomplish anything. With such an army and such high stakes Lee deemed the risks of a frontal assault on Cemetery Ridge, and the casualties it would incur, acceptable because the potential payoff was huge. But the man who had tactical command of the assault, Lieutenant General James Longstreet—Lee’s most experienced subordinate—thought the battle plan a bad idea. When Longstreet asked how many men would be in the assault and Lee estimated 15,000, Longstreet responded that no 15,000 men arrayed for battle could carry the Union position on Cemetery Ridge. Lee listened but disagreed, and Longstreet had no choice but to carry out a plan he believed would prove disastrous.

The attack failed badly. How did Lee confront failure? He might have sought to protect his reputation and sacrificed others in his army to atone for its failure. He could have cast a critical eye toward Longstreet or other subordinates. But he did not. Instead he rode out among his retreating soldiers, many dazed and shocked by the experience they had just passed through. The army needed leadership, not fault finding. He spoke to everyone he encountered and asked for their help. When he encountered an emotional General Cadmus Wilcox, whose brigade had suffered terrible losses, Lee shook Wilcox’s hands and said, "Never mind General, all this has been my fault—it is I who have lost this fight, and you must help me out of it the best way you can." A witness who observed Lee after the assault wrote, "It was impossible to look at him or listen to him without feeling the strongest admiration."[4] By assuming the full responsibility of defeat, Lee maintained harmony within his command and prevented the finger pointing, accusations, and dissension that can fragment and consume an organization after it encounters failure.

Meade and Lee stand as two of the most important figures in the outcome at Gettysburg; at the same time their stories are among the thousands of citizens’ and soldiers’ that also made history there. For students and other visitors to Gettysburg, these stories are made more real and accessible as they can see, touch, and contemplate the tangible site where so many made difficult decisions and terrible sacrifices.

"On great fields something stays," wrote Joshua Chamberlain. "Forms change and pass; bodies disappear; but spirits linger, to consecrate ground for the vision-place of souls."[5] Those who lived this dramatic and tragic event at Gettysburg still have something important to say to us when we stand in their footsteps and pause to ponder and dream and listen.

[1] Joshua Chamberlain, "General Chamberlain’s Address," in Executive Committee, Maine at Gettysburg (Portland, ME: Lakeside Press, 1898), 559.

[2] George Meade, ed., The Life and Letters of George Gordon Meade (New York: Charles Scribners’ Sons, 1913), 2:125.

[3] Meade, Life and Letters, 2:132.

[4] James Lyon Freemantle, Three Months in the Southern States (Lincoln & London: University of Nebraska Press, 1991), 269.

[5] Chamberlain, Maine at Gettysburg, 559.

D. Scott Hartwig is chief historian at Gettysburg National Military Park.